Balaka Abasan

When Shoven Ghosh Chowdhury started living in Balaka Abasan in January 2003, he was visited by a group of villagers from adjoining Thakurdari (now called Thakdari). “My ground-floor flat at the back of the complex looked out to a dense bamboo forest across the boundary wall. The villagers reported that the forest was haunted and were deeply concerned how the two of us would stay there,” recalls the man who was the first to move into the housing estate, which was the second project to be ready in New Town.

Though there were no supernatural encounters, challenges were in plenty. Reaching New Town on the first day itself was a tough ask. “There were no roads. My wife and I were moving in from Ballygunge. Our truck with the furniture sped over barren fields. Though the lanes inside the complex were paved, we had trouble figuring out which our B Block building was.”

There was no connectivity, barring stray auto rickshaws that plied. “If one auto came, the next would come not earlier than half an hour later. That is how we would reach the Kestopur bazaar, from where we would take another auto to reach VIP Road. Reaching office was a headache. When I returned in the evening, I would often find my wife pacing at the main gate in anxiety.”

Arati Pal, who moved in in May, made it a point to return before evening if she went out. “One day, I found no auto at the foot of the New Town bridge. A stranger who stayed beside the bridge asked his driver to drop me home,” recalled the 83-year-old lady, still full of gratitude.

Otherwise, she would get off at 215A bus stop and then walk across the bridge. “Autos were irregular,” said the lady who shifted from Baranagar after retirement.

Balaka

But the biggest drawback in the initial days was that there was no electricity. Ghosh Chowdhury realised that on his first visit before moving in. “I appealed to NKDA as it was impossible to live in the dark. They provided me with a direct power line. There was no meter box for the next two-three years but at least our purpose was served,” he recalled.

His immediate neighbour, Sangita Banerjee of the floor above, came in April. Then others, like Pal, started coming in a trickle. The early entrants benefited from the power line brought in for Ghosh Chowdhury till official connections were given.

“Our first Durga puja that year had around 15-20 families,” he recalled. “Those who had received keys were contacted by our committee and they all paid subscriptions. It was a very homely puja. I was elected president and also sang 10 songs over the three days,” said Pal, who also performed at Balaka’s Nazrul Jayanti last week.

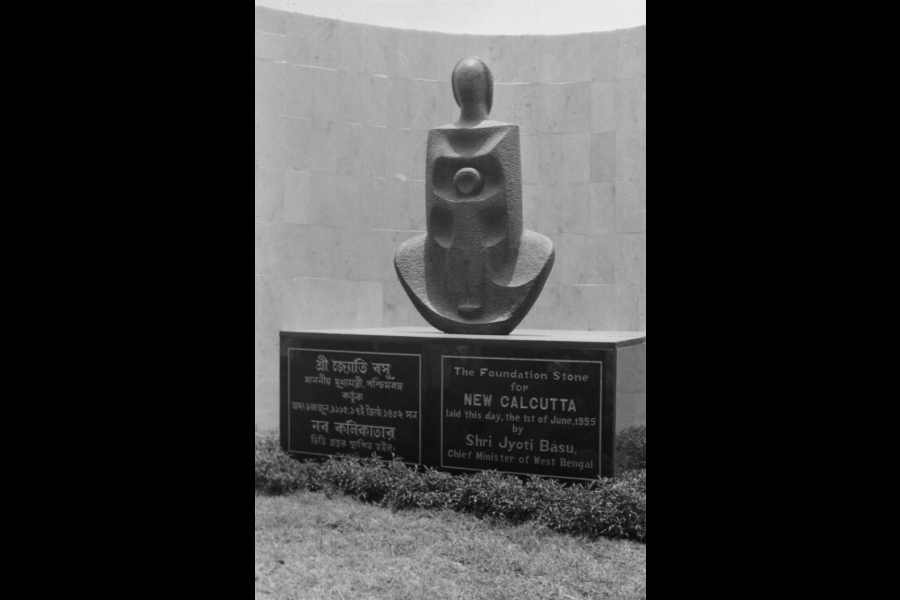

Foundation stone of the New Calcutta township at Rajarhat being laid by Jyoti Basu.

The Kestopur bazaar was their lifeline. “I would shop for seven days at a time. In the immediate vicinity, all we had were four shops — for tailoring, sweets, electronic appliances and electrical repairs,” Ghosh Chowdhury said.

Pal used to get fruits and vegetables from a haat close by in Thakurdari, near a Kali temple. “Now it has ceased to be. For everything else, there was Kestopur.”

Ghosh Chowdhury saw foxes and hyenas aplenty. Pal is still scared to name snakes, referring to them as “Ma Manasa”, the snake goddess. The complex used to get waterlogged in the monsoon.

Ghosh Chowdhury left New Town in 2016 and has settled in Birati. “I missed the advertisement for applications for East Enclave, which is close to Salt Lake. If I got a flat there, I’d not have left New Town. Balaka is too far within,” he lamented.

But Pal has been happy with her neighbours, ever since she succeeded at the lottery held in Bikash Bhavan. “I am unwell. Other residents are very caring,” the 83-year-old said.

East Enclave

The first housing estate built by the Housing Infrastructure Development Corporation in New Town welcomed residents in 2003. “We entered on Poila Baisakh that year, followed within a few hours by a neighbour in the opposite building. There was no running water in any tap,” Anil Pal said.

The 86-year-old, whose memory remains crystal clear, recalled how they drew water from the tubewell on the ground floor for the first two days till they got water supply at home. “Forget streetlights, there were no roads. Tokhon samne mati phelchhilo,” added his wife, Tripti, full of life at 78.

The couple remembers the inauguration of the Major Arterial Road. “They built a pandal where Nazrul Tirtha now stands. Jyoti Basu came, along with Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, housing minister Goutam Deb and sports minister Subhas Chakraborty on July 4, 2004,” Pal said.

They had got the keys to their flats at a programme on February 7, 2002. “The stage was built inside our complex, in the space between C and D Blocks. I received the key from Rajen Chowdhury of the West Bengal Housing Board,” Tripti gushed.

Life in a new township was tough. “It would be pitch dark in the evenings. I could see cars going towards the airport along that stretch of the road from my room. It felt eerie seeing the red backlights in the dark,” she said. Their only source of illumination was a couple of kerosene lamps.

“A neighbour who stayed at a far corner used to say that she took heart from the glow in our flat amid the darkness.” They liked the apartment so much that before moving in, even while they stayed on rent at Karunamoyee, they would often come to spend the day here.

“We carried a blanket and two pillows, and got off the bus at Sector V. Then we would walk all the way as nothing else was available. We would return by sundown.”

They had to fight to get every service. The two of them went to Telephone Bhavan, seeking a connection, on Pal’s scooter. “The officer was sending us away with a promise. But I dug in my heels, saying we would move in along with a working telephone. He relented and the very next day, our landline was installed,” the lady said.

She remembers seeing the streetlights come on on the Major Arterial Road. “I was looking through the window when it came alight. I screamed in delight.”

Among the others who got the keys on the same day was Narayan Dhar Chowdhury, a general surgeon. He was then posted in Raigunj. “I used to come to check on the progress of the construction when I visited on vacation. They were then laying the red brickbat layer, the third of the five layers of road construction. The bridge was also being built,” he said.

He remembered parking his Maruti 800 on the Mahisbathan side and crossing over on foot. The first day, he had snacked on curd being sold by a doiwala and was laid low with a stomach bug for five days, he recalled in horror.

During the lottery, Dhar Chowdhury’s elderly father was asked to draw the lots. “He was crestfallen on seeing the chit he drew did not bear my name. It was after a while that he remembered that the name was his daughter-in-law’s. Then he went to draw the lots for another category. As luck would have it, he drew my sister’s name. Aghast, the authorities relieved him of the job,” he laughed.

Though e drove around in his car, he recalled the distress of his wife, posted at Barasat Hospital due to the lack of public transport. “She had to walk all he way to the Kestopur market every day.”

“We didn’t have any post office or police station either. We offered space to the police to set up a thana in the garage space of our A Block. The station remained there for quite a while,” Dhar Chowdhury said.

The post office too was a result of a handwritten petition submitted at Kestopur post office, which got forwarded to Yogayog Bhavan. “A senior official came for inspection. He asked us for space but we had none to offer.

Finally they rented a floor in Mahishgote to start the postal index number code 7000156,” Pal said.

The residents also went to the Route 215A depot in Sector V, requesting that the buses terminate further up, at the space that was designated for the New Town bus stop.

As for daily supplies, while Dhar Chowdhury depended on the heat opposite what is now Utsa, the Pals would do their shopping at CK Market in Salt Lake. “Even after electricity came, power cuts were frequent and long. Once our stock of fish went bad after three days of darkness,” Tripti said.

On July 6, 2006, the East Enclave committee procured a van full of saplings from the horticulture department. “We sang in chorus and planted trees on both sides of our gate, along our boundary wall, towards Nazrul Tirtha, along Animikha Abasan, NKDA Market till Rail Vihar, though none of those structures existed. Nor did the footpaths,” Pal said.

East Enclave, the surgeon claims, is the greenest housing estate in Action Area 1, though he misses the migratory birds that used to come.

Millennium Tower

When Rupak Chakraborty would come to inspect construction of his future home in New Town from Behala, he would park the car on the other side of Kestopur Canal, cross a bamboo bridge near Balaka Abasan and walk across the fields.

Then the bridge connecting Sector V and New Town in front of Technopolis got built. “All the traffic on the new road was from the airport side. Hardly anyone entered New Town.”

He crossed the bridge along the right flank and entered the gate of the first housing estate to the right. “The MAR had no dividers in those days. Today we have to cross from the Nazrul Tirtha-East Enclave side and take a U-turn to reach our side of the MAR,” said the 58-year-old who is among the earliest residents of Millennium Tower.

Chakraborty set up a photo frame shop in Aahirini Market, but when a wine shop opened next door, he shifted his shop opposite Eastern High.

“Crossing the road was not an issue as there were so few people and cars then. Debashis Sen, who used to sit in the NKDA office next door, used to urge us to ask friends and neighbours, who had booked flats, to come and settle here. ‘Eto boro nordoma baniechhi. Lokjon nei, kaje lagchhena,’ he used to lament.

There were 144 flats at Millennium Tower. “Barely 35-40 families took part in our first Durga puja. So you get the picture,” Chakraborty smiles.

Their daily supplies came from sellers at a haat that would take place opposite what is now the Utsa complex. “A few sat with vegetables, three fishmongers were there and one chicken seller. We used to walk there for daily bazaar.”

There was no bus service initially.“An auto rickshaw route from New Town bus stand to Karunamoyee was our mode of public transport. It used to cost Rs 5,” Chakraborty recalled.

There was no Nazrul Tirtha or Coal India office when they were handed over their keys in 2006. Animikha was under construction and Eastern High would start soon after.

“We used to watch cattle grazing all around from the roof. There were only East Enclave across the road and the NKDA office to the left. And since there were so few officers at NKDA, we knew them personally and resolution of all issues was quick.”

Water supply was a big headache because of high iron content. “Sokale rakhle bikele balti laal hoye jeto,” here called. That meant installation and repeated replacements of iron filters.

But there were no problems of water-logging in Millennium Tower unlike at Animikha on the other side.“We are also the first housing estate in New Town to have a swimming pool,” he said.