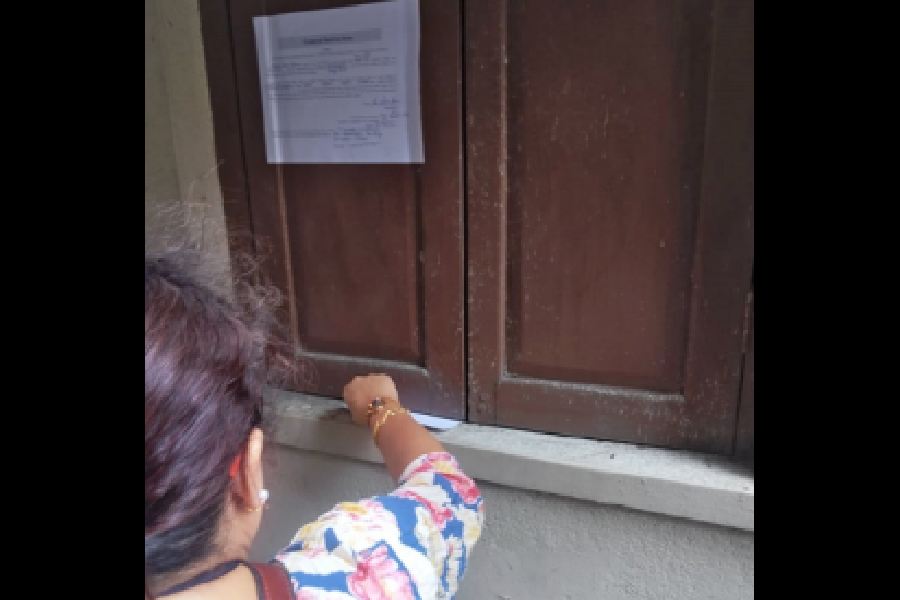

- A booth-level officer (BLO) pasted a notice on a closed window before sliding an enumeration form through a slit underneath. The house, in Behala West, belongs to an elderly woman who has been living with her daughter in Delhi since her husband’s death. Though she remains a registered voter here, her absence has complicated the verification process.

- At another address nearby, the BLO found a 90-year-old man confined to his bed. His wife is dead, and he has no children.

- A third house was locked because the father and elder daughter had died, and the mother now lives with the younger daughter elsewhere.

A Wednesday drive for the special intensive revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in a small pocket of Behala revealed how tricky the process can be.

Soumi Saha Barua, a schoolteacher and BLO for Ward 126 in Behala Bakultala, encountered multiple challenges while going from house to house.

At the first residence, a two-storey house, the doors were locked. A tenant living in another section answered the doorbell and called her landlady. After a brief conversation, she relayed the message: “She does not want to talk, madam.”

Madam remained polite but firm. “Please tell her that I am on government duty,” said Saha Barua.

The approach worked. The tenant shared the landlady’s number, and the BLO sat on the staircase at the entrance, speaking to her over the phone.

“She said she would try to return before December 3 and sign the enumeration form. But it will be difficult for her to travel alone,” Saha Barua later told the booth-level agents (BLAs) of Trinamool and the CPM who were with her.

“We came here because her name is on the current voter list. If she can’t come back in time, I don’t know what happens next,” she added.

Following protocol, Saha Barua then pasted a notice, signed by her, on the window and slid the enumeration form into the house. The notice must be displayed “at the residence of the elector/person in case no family member is found at his residence.”

It read: “I appeared at your residence... but found (it) locked, so I slipped the Enumeration Forms in the house. I will make at least three visits to collect the filled up forms, so I will be present at your residence on dates (she wrote three dates down, the last one being December 3)... to collect the filled-up Form... If you are not found at your residence... then the Electoral Registration Officer will be informed about your absence...”

The house enumeration phase, which began on Tuesday, will continue until December 4.

In the same neighbourhood, Saha Barua met the 90-year-old bedridden man. Apart from an ayah, there was no one else at home. A neighbour informed her that the man’s wife had died and that the couple had no children. A nephew visited occasionally.

The BLO asked the ayah for the nephew’s contact and called him. “I need to take the voter’s left thumb impression on the form in the presence of a relative. A postal ballot can be arranged for him if he wants,” Saha Barua told the nephew.

A few metres away, another house stood locked. The BLO’s copy of the current electoral rolls listed four voters — a man, his wife, and their two daughters — at that address. A neighbour provided the younger daughter’s number.

When contacted, the daughter explained that her father and elder sister had passed away, and her mother, now unwell, lived with her at another address.

“Please visit this address and let me know in advance,” Saha Barua told her. “I will give two enumeration forms. For your father and sister, I will need copies of their death certificates.”

When the daughter asked if the officer could visit her current home, Saha Barua declined, saying she could not because physical verification had to be done at the address listed in the rolls.