|

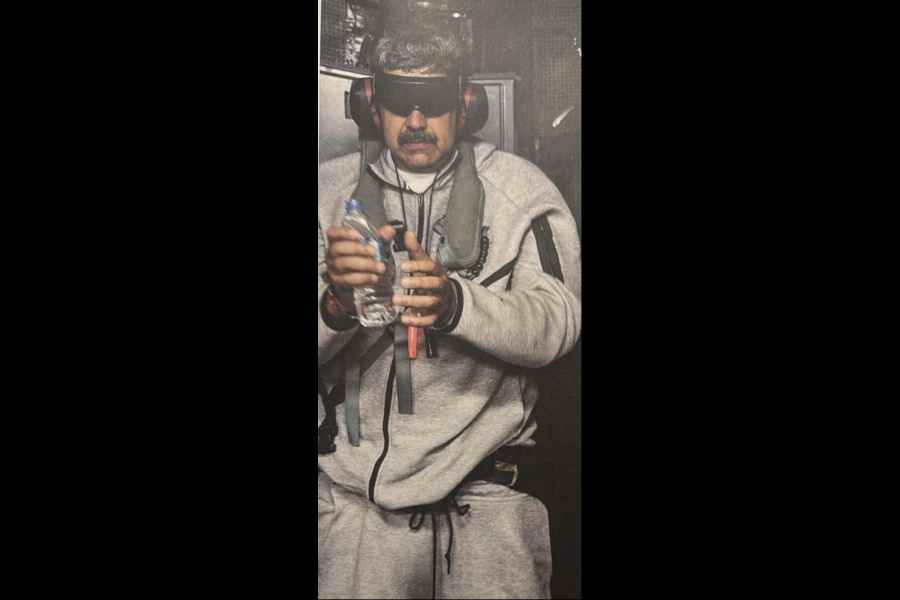

| Pradip Rudrapal takes a break from making Durga idols to work on a fibreglass sculpture |

Kumartuli is also an emporium of kitsch. Not only of the Hindu variety. Pradip Rudrapal’s studio at Telengabagan, a few kilometres from Kumartuli, is strewn with his artwork. Most of it is made of fibreglass. The door to his inner office is carved with the image of Christ on a cross and his devotees. A panel on a wall is sculpted with two horses, a shelf in a corner has a carved base in the shape of a Victorian maiden.

Pradip, son of legendary idol-maker Mohan Banshi Rudrapal, a patriarch who is among the most eminent artisans in Kumartuli along with Ramesh Pal, says that his art college degree has helped. “It is a highly competitive world and a certificate helps,” he admits. He is mostly into sculptures and works with mediums like fibreglass, toxicity notwithstanding, metal and stone.

“Fibreglass is cheaper, the price of metal artwork is decided by its weight.” The rate varies. Pradip Rudra Pal charges Rs 10,000 per square feet of fibreglass artwork. He works with interior designers and architects and holds exhibitions of his work.

Neglect and nostalgia

Kumartuli occupies a special place of respect and nostalgia in every Bengali’s heart. This is where “Ma” is brought home from every year. Now, more than ever, it seems respect and nostalgia are not enough to live on. Not many of its young want to be idol-makers.

As business declines steadily, despite Puja pandals getting grander and bigger-budgeted by the day, the younger generation at Kumartuli is trying its hands at different professions to rise above the squalor and poverty of its muddy, dirty lanes. The more successful have “diversified” into artwork — decoration pieces, film sets, statuary. Lifestyle is more lucrative than pure tradition.

|

| Niranjan Pal |

|

| Mohan Banshi Rudrapal |

Sometimes the father doesn’t want the son — idol-making is one of the last male prerogatives, a skill almost always handed down from father to son — to enter the profession. Perched on a high stool in his dingy little studio, Nemai Chandra Pal is intent on giving form to the face of a Durga idol. A scrap of tarpaulin hangs at the entrance in an effort to keep out the sporadic rain. With only a few days to go for Puja, the 61-year-old president of the Kumartuli Mritshilpa Sanskriti Samity is a busy man. His family has been in Kumartuli for five generations.

Behind the studio, in his room, sits Nemai Chandra Pal’s 23-year-old son Goutam, surrounded by his books and pets. He is determined idol-making will never be his profession. He has done a course in veterinary medicine and earns about Rs 2,500 a month working part-time as a trainer and breeder. He wants to be a teacher.

Nemai Chandra Pal is supportive of his son’s decision. “As long as I am working, I’d like him to help me if I need it. But I don’t want him to make this his profession,” says the father, with vehemence.

Pull of the past

It was not as if the olden days were golden at Kumartuli. Youthful rebellion and discontent with one’s lot had always spurred the young ones to strike out. Niranjan Pal, 90, one of the oldest members of the Kumartuli community, remembers that he didn’t want to step into his father’s shoes.

“I tried many things, before becoming an idol-maker,” says Niranjan. The older artisans would make other items like little dolls, or models, or even items for decoration, but they were primarily idol-makers, whereas for the youngsters artwork is the main profession with idol-making just a seasonal business. Nemai Chandra Pal didn’t want to be an idol-maker either. “I graduated in zoology and wanted to become a doctor. But when my father fell ill, I had to enter this business. It was a mistake,” he says.

The prodigal sons would return. Babu Pal, 41, joint secretary of Kumartuli Mritshilpa Sanskriti Samity — this union has 320 members; the other union of idol-makers, the Kumartuli Mritshilpi Samity, has 100 members — had closed down a hosiery business to take up his father’s profession of idol-making 15 years back. “It was a lucrative business then. We even sent idols to Nepal,” he says. As Niranjan Pal recalls: “There was a pull from within. I had to do it.” The beauty, the spiritual dimension of idol-making and the fact that a family profession is a comfort zone kept the young men in the fold. But now things are quite desperate. Nemai Chandra Pal says his father maintained a family of 10 but was never heard to grumble about money. Today Nemai cannot maintain a family of three.

Beyond idols

Hence the diversification. “My father does not approve of theme pujas,” says the 42-year-old Pradip Rudrapal, who has a master’s degree in fine arts. Mintu Pal, joint secretary of the Kumartuli Mritshilpa Sanskriti Samity, whose family has worked from Kumartuli for three generations, supplies idols to temples, works with interior designers and also makes images of famous people as decoration. “I make other art objects through the year. Only 30 per cent of my annual income comes from idol-making,” says Mintu, 45, a father of two. “There’s a demand for fibreglass work at film studios.” Artefacts can fetch from a few thousand rupees to even over a lakh rupees, he says.

|

| Nemai Chandra Pal gives form to a goddess’s face |

Jayanta Pal, 22, who has passed Higher Secondary, is into such artwork. In the months before Puja, he helps his father make idols. He is also in demand because of his expertise in lining the eyes of goddess. But after the pujas, he is engrossed in art of a different kind. “I make film sets and clay models. There is good demand for such work and it pays well, sometimes as much as Rs 3-4 lakh for one assignment,” he says. He would like to get into an art college to broaden his horizon.

Kaushik Ghosh, in his thirties, is a major exporter of Durga idols. His family, unlike the idol-maker Pals, has been into decorating idols for four generations. But he makes fibreglass idols for export, plus decoration. “I do stage decoration, doing up festival and seminar venues,” he says. Ghosh has his own website.

Why does idol-making face such difficulty even as pujas become more spectacular?

“The number of Durga pujas held in Calcutta has not increased much in the last decade. This is because there are several rules and regulations that have to be followed today to organise a puja. You need permission from the authorities, which is not easy. Approximately 4,000 pujas are held in Calcutta (including Salt Lake) now,” says art historian Tapati Guha Thakurta.

Lack of skilled hands

The style of the celebration has changed over the past seven-eight years, especially with the advent of the “theme puja”. “A whole new creed of artists and designers has entered the field,” says Guha Thakurta. Many theme pujas involve art school graduates. It has meant more competition for Kumartuli’s men.

Many artists have moved out of Kumartuli. “The Kumartuli images market has not really increased. The next generation of artistes, those who have studied at the art school, are, therefore, trying to widen the scope of their work and attempt new designs and themes,” says Guha Thakurta. There is, perhaps as a result, a pervasive sense of the failure of tradition.

“There will be no one to look after the business after me. But this business has nothing to offer anymore,” rues Nemai Chandra Pal, even as he doesn’t want his son to become an idol-maker. There is a real fear that there may not be enough skilled artisans in the Kumartuli tradition in the near future. A kaarigar, the help-labourer to the idol-maker, may save the business by buying it (though idol-makers do not look forward to be replaced by kaarigars). It has happened before. There were kaarigars whose sons are master-craftsmen today.

“But even the number of kaarigars is dwindling. Earlier there used to be children who would come to work with the master, learn from him and work as his kaarigar. Today there is a dearth of such people,” says Pradip Rudrapal.

|

| Chairs designed by Pradip Rudrapal at his office |

Money trouble

There are other, age-old problems.

“The cost of labour and raw materials has hit the sky. In comparison, the price of idols has not gone up so much. If my father cornered 70 per cent profit from an idol, today I am earning only 40 per cent,” says Babu Pal.

The price of idols has increased from Rs 5,000-6,000 for a 10ft idol back in the Seventies to Rs 20,000 today. But the cost of production has risen even more. “It takes around Rs 12,000 to make an 8-9ft idol. Of this Rs 5,000 are labour charges. Raw materials such as bamboo, straw, nails, rope and paint cost another Rs 5,000. Rs 2,000 is spent on dressing up the idol,” says an artisan.

New government regulations cause further woe. “The pollution control board wants us to use lead-free paint, which is expensive. But customers won’t pay more,” says Nemai Pal. After dues have been cleared, the artisans say, they are left with approximately Rs 1.5 to 2 lakh. This has to support them through the year, for idol-making remains a strictly seasonal employment.

A part of the earnings goes to clear bank debts. “We get about Rs 2 lakh loan before the pujas, at an interest rate of 10.5 per cent. This we have to repay in a year,” says Babu Pal.

Competition leads to undercutting neighbouring artisans, resulting in a general drop in prices, says Pradyut Paul, an exporter of idols from Kumartuli. So things get caught in a circle, rather vicious.

Hence Goutam Pal, son of Nemai Chandra Pal, wants to be a teacher. Or Subhankar Pal, son of Dilip Pal, who has started a catering business.