|

At one time, most female circus artistes used to be from “Madras” — which in common parlance means south India. These “Madrasi” girls used to be short and stocky but they could “fly” effortlessly and their limbs were as supple as rubber. Reba Rakshit, that Bengali star of the big top, could bear the weight of elephants and large vehicles on her chest. But few seem to remember her today.

Saibal Das’s black-and-white photographs of circus girls now being exhibited at Seagull Arts and Media Resources Centre reveal that those southie belles are no longer in the Barnum & Bailey world. With new job options available in the South, most women from poor families prefer to take up nursing assignments or go to the Gulf to in search of bread.

A frail woman lies on her bed. A former circus artiste, now a typical elderly housewife from the south, she is back in her village post-retirement. Besides her, most of the young ones photographed here are from Nepal. These girls could easily have ended up in the flesh trade but they still look vulnerable in their cheap and tawdry gear.

Das, who used to be a press photographer, took these photographs with an analogue camera in 1997, when he travelled from Jaipur to Vellore. He had won a scholarship to do this project on the theme of women in circus. Digital prints are on exhibition because apparently bromide of such large dimension is not available.

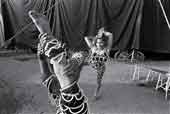

But why go in for such large prints? The grey areas have suffered as a result. Nonetheless, the photographs are poignant without parading the Raj Kapoor variety of maudlin. Das documents and celebrates the moments of solitude and togetherness in the lives of these artistes who make a meagre living by showing off their “unnatural” acts. A clown is the centre of gravity of a composition which shows the freshers exercising. A woman in heavily beaded tights exhibits her four legs and an equal number of arms. Another laughs gleefully amidst a gaggle of geese outside her tent.

Some of the most revealing photographs are those of the girls barely out of their teens on their own, impervious of the camera clicking away. One girl is at her toilette, vigorously combing her hair. The second sits on her cot with her legs outstretched. The third is just a heavily made-up face, seemingly in meditation superimposed on the printed, crumpled bedsheet. The subject stands beyond the camera but the rectangle seems like a slice of reality from elsewhere.

In another frame, four girls huddle together waiting to be called for action. A coiffed profile occupies the middle of the frame. She wears a pensive expression and plastic earrings. Another girl behind her looks straight into the camera. A butterfly is sequinned on her meagre torso. A contortionist merrily twists and turns her limbs in impossible angles amidst the domesticity of her tent.

These portable shelters are a constant presence in this entire show. The artistes share their closest moments inside or outside these, perform their bizarre acts under these and hone their skills to perfection in close proximity to these mobile homes and workplaces made of fabric.

Das has the sharp eye of a photojournalist and the sensitivity of an artist.