Dental surgeon and wildlife enthusiast Supriyo Samanta was out photographing waders on the Mandarmani coast in the summer of 2011 when he caught sight of what looked like an unusual bird flying overhead.

"Within a second, I saw another one. Then I turned around and observed many more flying eastwards over the coast. The flock grew larger as the seconds ticked by, the spectacle lasting almost 20 minutes," he recounts.

Samanta's serendipitous encounter with the Amur falcon over the Bengal coastline remains one of his fondest birding memories. "I felt very lucky seeing this wonderful bird in such huge numbers on its return migration, moving along the Bay of Bengal," he says of that experience.

There are prior and later records of the bird being spotted over Calcutta's concrete jungle too. A decade ago, banker-turned-conservationist Sumit Sen had photographed an Amur falcon flying above his Jodhpur Park home. It was also photographed at Rajarhat in 2012, near Victoria Memorial in 2013 and on the Baidyabati canal in Hooghly district in 2014 and again last October.

What makes all these sightings special is that the Amur falcon is not just another beautiful bird. This small red-footed raptor's long, arduous journey back to Mongolia, north China and Siberia every year after spending a part of winter in South Africa is an epic story of survival.

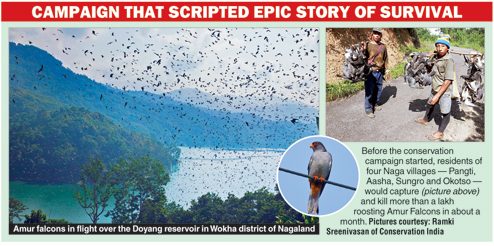

On its way to South Africa, the Amur falcon makes a stopover at the Doyang reservoir in Wokha district of Nagaland, where it once used to be hunted for its meat in large numbers.

Metro travelled to Pangti village, adjacent to the reservoir, last winter to gain an insight into how a group of conservationists got together less than five years ago to help stop the largest massacre of birds anywhere in India.

Predator to protector

Thungdemo Yangthan is more than happy to show you around Pangti village, especially the roosting sites of the Amur falcon along the Doyang reservoir. But don't mistake him for your usual tourist guide.

Until around 2012, Yangthan, 38, would kill about 150 Amur falcons a day between mid-October and mid-November. His transformation from hunter to protector is part of the extraordinary story of how the annual bird massacre stopped.

Tenny Lotha, in his 30s, used to do the same. Capturing the birds and selling them would fetch him around Rs 30,000 in four weeks. He now runs a tea stall in a large field where tourists gather to witness the birds in flight or roosting on the trees surrounding the reservoir.

Before the conservation campaign started, residents of four villages - Pangti, Aasha, Sungro and Okotso - would kill more than a lakh birds in about a month.

"On my first visit to this place in 2012, I saw many people walking with birds tied to a stick each resting on their shoulders. I spoke to them and got to know that they had captured the birds for meat," recalls journalist Bano Haralu, managing trustee of the Nagaland Wildlife and Biodiversity Conservation Trust.

Haralu was visiting Pangti with conservationists Ramki Sreenivasan, Shashank Dalvi and Rokohebi Kuotsu. Their mission? To convince the villagers to stop a practice that even a government ban had failed to do.

Pressure to protect

The 2012 campaign to save the Amur falcon prompted the government to issue a fresh notification banning the annual slaughter. Enforcement had been non-existent till then. Suddenly, the authorities were under pressure to act as information about the massacre spread worldwide through a series of articles documenting the practice.

A directive from the Union government, which is a signatory to the Convention on Migratory Species, led the forest department of Nagaland to hold meetings with the community. The governing councils of the villages surrounding the reservoir were told that flow of funds for development would stop if hunters were allowed to continue killing Amur falcons.

Haralu and her fellow conservationists set out to fill the great awareness void that the government had ignored. "I realised that like everywhere else, there was a lack of knowledge about conservation. I told the villagers that this bird feeds on termites that destroy their crops. I tried to inform them in a way that they realised the importance of the bird to the survival of their crops," she said.

The team returned in 2013, camping in the villages from August onwards to carry the campaign forward. Wildlife educators from various parts of the country joined in to help spread the message. The turnaround had begun.

"I think the villagers realised that this (hunting the Amur falcon as a means of income) was not sustainable. They understood that if they continued killing the birds every year, a day would come when there would be no Amur falcons left in the world," says Haralu of the success of the campaign in a state where hunters with airguns on their shoulders and kids with catapults is a common sight.

The challenge

More than four years later, keeping the enthusiasm for conservation alive among the villagers is the new challenge. Some have already started questioning why they have received little in return for stopping a practice that was an additional source of income. "We need help. I used to earn Rs 30,000 by selling these birds. I understand that killing the birds is wrong, but the government should also do something in return for us," says Tenny.

Yangthan earns Rs 4,000 from the government for keeping vigil on the birds during their stay in Doyang, but he fears that the villagers would go back to hunting the Amur falcon if the reward of compliance does not come soon.

Tourism during the migration season is a potential source of income for the locals, although it is a long way from being an organised industry. More than 2,000 people had visited Doyang in 2015 just during the three weeks that the Amur falcons were there.

The underlying fear is that a tourism boom would destroy the character of the place and maybe even its ecology. "Tourism here must be dependent on homestays. But the villagers' houses are not yet ready to keep tourists," says Sanjay Sondhi, a wildlife educator who has been visiting Pangti since 2015.

Some members of the Amur Falcon Roosting Area Union had declared last October that they would bar tourists until the government fulfilled its promise of development. They were dissuaded from doing so, but nobody can tell if the stirrings of protest will be back this year.

The takeaway

The spectacle of about 1.5 lakh Amur falcons flying in the sky over a range of 25sqkm is an appropriate reward for the trouble anyone takes to visit Doyang, about 140km from the nearest airport in Jorhat, Assam.

Veteran birders call the Amur falcon congregation among the largest for a bird of prey anywhere in the world. From the ground, the sky looks like a blue canvas dotted with black spots as you approach the roosting zone. When the birds fly closer to the ground, they are a sight to behold with their red to pale orange cere and eye ring.

Males have a dark, sooty grey back. The thighs, vent and undertail coverts are reddish brown. Females are slightly larger and paler, with dark scaly markings on white underparts.