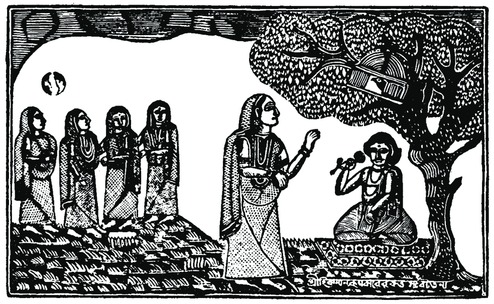

on his way to Burdwan; (top) Hiralal Karmarkar’s Sundar

The play ran through the night. The production was recklessly lavish. The wealthy Babu Nabin Chandra Basu had spent over Rs 1 lakh to create something resembling a European proscenium with stage equipment imported from England. Since there were no professional women actors at the time, he hired and trained prostitutes to play the female roles. Dressed in exquisite costumes and elaborately designed jewellery, their histrionics impressed the audience - 300 of north Calcutta's gentry.

That was in 1835.

There was no proper stage for the performance, so the different acts were staged in different parts of Basu's palatial mansion at Shyambazar, where now a tram depot stands. The audience, who had seen nothing like this, watched and cheered while enjoying a grand dinner.

The play being staged, Vidyasundar, was a dramatised version of an episode from poet Bharat Chandra Roy's 18th century classic, Annada Mangal.

Almost 200 years after Babu Nabin Chandra Basu's production, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations will present Vidyasundarer Gaan this month at Calcutta's Abanindranath Tagore Gallery. Classical singer and expert on Bengal's theatre heritage, Devajit Bandyopadhyay, and his wife Riddhi will sing the forgotten songs. Bandyopadhyay, in fact, has curated the songs that go back three centuries.

The poet Bharat Chandra had been the first to liberate poetry and musical compositions of Bengal from religious trappings. Most early plays and jatra (folk theatre) would be centred around gods and their exploits. Says Bandyopadhyay, "Since they were divine beings, no playwright could cross a certain [moral] boundary."

But Bharat Chandra's hero and heroine - the Dravidian prince, Sundar, and the princess of Burdwan, Vidya - were mortals. The godly touch was not altogether missing - in their previous birth they had been lesser gods who were banished from heaven for their illicit amour. "But their mortal incarnation allowed Bharat Chandra to narrate their romance and sexual escapades in a manner that was till then unexplored," adds Bandyopadhyay. Vidyasundar traces the couple's earthly incarnation and continuing romance.

According to Bandyopadhyay, way before Basu's extravagant experiment, it was the Russian scholar-adventurer, Gerasim Stepanovich Lebedev who first sensed the musical potential of Bharat Chandra's poetry.

It was Lebedev who founded the first European-style proscenium theatre at Ezra Street in Calcutta. The theatre opened in 1795 with Kalpanik Sangbadal, the Bengali translation of an English comedy titled The Disguise. The music of this play was composed by Lebedev and the lyrics were borrowed from Vidyasundar.

Lebedev's musical was successful but the British administration was not happy with his experiments and much annoyed by his sympathetic stance towards the natives. After Lebedev lost a court case against a British employee, a decorator at his theatre, he was financially broken. Eventually, in 1797, the British authorities expelled him from India.

But Lebedev didn't lose his love for Vidyasundar or Bharat Chandra. On his way back to Russia via London, he wrote to the Russian ambassador in London about publishing Bharat Chandra's works in Russia. Later, he translated parts of Annada Mangal, including Vidyasundar, into Russian. In fact, one of the five extant manuscripts of Annada Mangal can be found in the Central State Moscow Historical Archives. The others are at London's British Museum, the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and the Asiatic Society in Calcutta.

The Westernised elite of Bengal found Bharat Chandra rather obscene. The Babus, however, lapped up the musical with gusto. Many members of the gentry even trained actors and actresses to enact the play at street corners. For instance, Gopal Das, popularly known Gopal Urey, a fruit vendor from Jajpur near Cuttack, was trained to perform Vidyasundar by one Babu Radhakanta Sarkar in the 1840s.

"Gopal improvised many of these songs and these were immensely popular," says Bandyopadhyay. Gopal's rendition of Vidyasundar inspired the stage productions of Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Dinabandhu Mitra, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and even the Tagores, Jyotirindranath and Rabindranath.

Later, Vidyasundar was adapted several times for the stage and was also turned into a movie in 1935. Says Bandopadhyay, "With the passage of time, the saga of Vidyasundar continued to exercise a profound influence on popular psyche."

As the narrative goes, angered by the dalliances of Vidya and Sundar, the King sentenced the latter to death. And he would be dead had it not been for Annada, a goddess who descended on earth to save him.

The more things change, the more they remain the same.