|

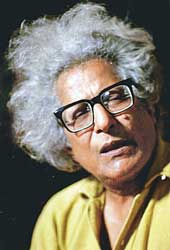

Subhash Mukhopadhyay, who died in Calcutta on Tuesday morning at the age of 84, had ushered in a new era of down-to-earthedness and revolutionary fervour in Bengali poetry with the publication in 1940 of Padatik, his book of poems. He rejected outright the high falutin in favour of the rhythms and vocabulary of everyday speech, and in both rhymes and blank verses experimented with metres and syllabic divisions.

His greatness lies in the fact that Mukhopadhyay evolved from time to time, says Joy Goswami. He never rested on his laurels where his language was concerned. Even in his last days when he had fallen ill, his sense of humour had not abandoned him. He would poke fun at the decrepit old man he had become.

In his last published poem, he was yet the radical of his Padatik days. Mukhopadhyay spoke of the urgent need to act and bring about change instead of speaking about it.

Nirendranath Chakrabarty says Mukhopadhyay had opted for a very workaday way of life that was reflected in the language of both his prose and poetry. Mukhopadhyay never felt there was any need for a poetic diction. Like Wordsworth, he wrote in the “living language of men”. Breaking down the barriers between poetry and prose, he infused a new vitality in literature.

Chakrabarty asserts that Mukhopadhyay may have been a Marxist to the last, but even those who were on the opposite ideological pole could not help liking this poet. He also had a keen sense of humour which often informed his poetry. Very fond of fishing, he would go to the Hooghly quite often. Once he used a sweet as a bait. “Fish never get to eat dainty morsels. Perhaps, one will rise to the bait,” Mukhopadhyay had said.

Buddhadeb Basu, who was himself a figurehead of the post-Rabindranath era, seemed to have been overwhelmed by the brilliant improvisations of this young poet, for Mukhopadhyay had struck out on his own both in metrical construction and also in the area of themes. In spite of his revolutionary zeal, he had won over the establishment and in 1991 was awarded the Jnanpith.

Born in Krishnagore, Mukhopadhyay was deeply involved in Left politics right from his student days. When he became a cult figure almost overnight, many of his poems could be interpreted as slogans of Marxist parties and were exploited as such.

Assessing Mukhopadhyay’s contribution to Bengali verse, Shankha Ghosh says he was a political person in the deepest and profoundest sense of the term. “His writing was deeply rooted in the human situation, the many obstacles one faces and tries to overcome. Mukhopadhyay felt he could never write unless he could wander keeping his ears open to the speech patterns of ordinary people. No other poet wrote in a language so idiomatic.”

Ghosh says Mukhopadhyay wrote about leading a simple and beautiful life and about the difficulties in doing so. So his writings always reflected the political struggles of contemporary life.

But when his fellow travellers themselves became rulers the struggle seemed to have become redundant.

So the Marxists who had once lauded him rejected him.

The saddest irony of it was that this man who had himself taken part in so many political rallies went on a lonely and forlorn last journey to the burning ghat on Tuesday evening.

The political parties that once considered him their mouthpiece had abandoned him. When Joy Goswami went to the burning ghat, only a single individual had turned up to pay his last tribute to the poet.

Perhaps this was a fitting end to the life of a poet who never sought acclaim as a poet. All he wanted was to wander amidst people till the last days of his life.