|

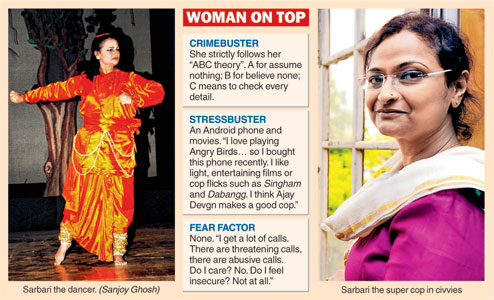

When a shy political science student harbouring dreams of becoming a professional dancer traded her ghungurs for a gun holster, she morphed into Bengal police’s ace shot against gangs of human traffickers.

“If not join the police, I definitely would have been a dancer,” insisted Sarbari Bhattacharya, the 49-year-old chief of the state CID’s anti-human trafficking unit.

“I was passionate about dancing… Bharatanatyam, Rabindrik, folk. I never even thought I’d work, let alone work for the police. I used to watch this serial called Udaan (aired on DD between 1989 and 1991) about a lady IPS officer. It’s based on a real story and drew me to the world of policing. I felt the need to create my own identity and empower myself,” said the officer who enlisted as a sub-inspector in Malda in 1989.

It wasn’t easy for the only girl training with 220 boys. “No one thought I’d be able to complete the training because it involved everything from horse-riding to firing rifles. Back then, a girl competing with men wasn’t the done thing. I had to endure taunts even after completing training and got my first posting in Malda.”

She carried on despite condescending comments from some of her male seniors. “Don’t wear the uniform, you attract attention. Or, you cannot go alone to raid a house at night. I heard them all.”

But the young sub-inspector found a boss who supported her to the hilt. “SP R.S. Rawat made me realise for the first time that there is nothing called a lady sub-inspector. You’re either a sub-inspector or you’re not. Since then I stopped being submissive.”

“When a woman takes charge of something, she can be deadlier than any man. I am deadly because nobody gave me an outside chance!”

She was drafted into the protection of women and children section as additional officer in-charge in 2009 after a long stint in the intelligence branch, which helped her sniff out the cons from the pros.

Sarbari hit the ground running and rescued a Bengal girl from a Delhi prostitution den in 2010. The 15-year-old was missing for more than a year — last seen at the tent of an itinerant circus in her village.

The police officer tracked down a phone number and befriended the trafficker over SMS. “From exchanging ‘goodnight sweet dreams’ over SMS to agreeing for a trip with him to Goa, I trailed his moves till I could nab him.”

“It was a challenging case and prompted the state to focus for the first time on trafficking,” she said.

Success came in a bouquet of praises, even from Calcutta High Court, and the government set up the anti-human trafficking unit (AHTU) — a specialised wing of the CID — in 2011 with Sarbari at its head.

“The case was a turning point. It fired up my passion. I feel a personal responsibility towards these trafficked women. Maybe because I have a daughter,” she said.

Her instinct was spot-on when she rescued a woman, 22 years after she went missing as a child. It took her just a year to crack the case.

Despite the police’s best efforts, Bengal is saddled with the ignominious record of having the highest number of missing women in the country. Girls continue to disappear from rural Bengal — horribly beaten and raped to submission and sold to brothels across the country.

“When I go to cities outside Bengal on rescue missions, I have to hear statements like ‘Madamji, arrey har ladki toh Bengal ki hoti hai. Ek aanchal phela doh, do-sau ladki toh waise hi uth jayenge (Every girl is from Bengal. Cast a net and 200 girls will fall into it)’. It makes me angry and upset. I need a highly organised unit to tackle this organised crime,” she said.

A year into her new assignment, a frustrated Sarbari thought of quitting. “Cases were piling up and I didn’t have the manpower, accommodation or basic infrastructure. It wasn’t about trying and failing. It was about not being able to make an attempt.”

Her inner voice held her back. “I saw girls being sold at Rs 200 per hour and attending to 25 customers a day. I made up my mind that I can’t leave. There’s more to it. It’s a fierce maternal instinct that keeps me going,” she explained.

A colleague said: “She has a unique approach, more like a mother than a policewoman.”

In January this year, she busted an international trafficking ring spread over Bangladesh, Basirhat and Ahmedabad. Barely two months later, the court sent two traffickers to prison and lauded the police in landmark judgment.

Sitting at her Bhavani Bhavan office, she said some more money and manpower could have made a lot of difference. “Our staff is overburdened with critical cases requiring swift raids across the country. How can I expect them to perform well when basic things cannot be provided? There isn’t space in this small office to let each officer have a chair and a table, let alone a separate room to question an accused.”

“We need a laptop, modern tracking devices that I’ve seen in Delhi and special incentives to motivate the staff. These are basics needed to encourage more officers to join this wing,” she added.

She said the state’s porous international border posed a big challenge but “ignorance and poverty are equally responsible” for making Bengal a trafficking hotbed.

Not all trafficked girls or women land in brothels, she said. “Many are abducted or lured to distant places to serve as domestic helps. Some are sold as brides in north Indian villages having a skewed gender ratio. They are initially tortured and then brainwashed… showered with perfumes, make-up kits and clothes as gifts. Ninety-nine per cent of such girls don’t want to return home, unaware that they are being used as merchandise.”

To reverse this mindset, Sarbari said there should be a strong and effective rehabilitation system. “Compensation is a far cry while vocational training doesn’t economically empower a girl as much as it should. The social welfare department should be more focused. What’s the point in rescuing a girl if she continues to be vulnerable?”

When she is not chasing criminals, she hosts awareness programmes and organises workshops in schools and stages street plays.

And the subdued dancer still fights to get out of the police uniform!

Sarbari choreographed Tagore’s Chitrangada and performed as Arjun with the girls she rescued at Rabindra Sadan last Durga Puja.

“After many many years, I took to the stage because that would motivate the girls who are now in rehab.”