|

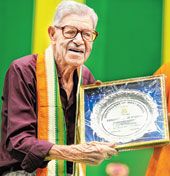

| Keshav Datt at a recent felicitation by the sports department. (Santosh Ghosh) |

The story of the triumph in 1948 has to start from the tragedies of 1947. No one felt it more keenly than Keshav Datt. A Lahore boy, Datt was playing the final of the Inter-provincial Hockey Championship in Bombay for Punjab when the Partition was declared. “My mother sent me word not to return to Lahore. Riots had broken out and they had all fled. But our Muslim teammates assured me that it would be safe,” says Datt.

When he reached his hometown, Lahore was engulfed in silence of the grave. House after house was emptied of all signs of life. In the evenings, blood-curdling slogans would rend the air. “I had taken shelter in my teammate Shah Rukh’s house. Not only were we friends from school and college, we also played shoulder to shoulder in the Punjab team. But after a week, word spread that he was sheltering me.”

To save his life and his friend’s, Datt fled to Delhi. “Shah Rukh saw me off at Lahore station.” That was the last that the two friends met. Till London 1948. In opposing teams.

Meanwhile in Kharagpur, Leslie Claudius had switched from football to hockey on the advice of hockey star Dick Carr. “Hockey was more popular than football,” he recalls. A good showing in the Beighton Cup in 1946 meant young Claudius, a right-half, was ready for national duty.

|

| From Datt’s scrapbook: The victorious Indian hockey team in Delhi after returning from the 1948 Games |

Jaswant Singh Rajput, who played left-half, got selected from Delhi. “The Partition did not hit us much in terms of available talent. Just one player from across the border could have walked into the squad — A.I.S. Dara (from the 1936 Olympic team who became the captain of Pakistan). We had enough good players to send two teams to London,” he says. But with so much killing and rioting going on, many were against participation. “It was a brave decision to send a team to London,” says Datt, a centre-half, who by then had started playing for Bombay.

London ahoy

While the rest of the Indian contingent left by ship in June the hockey team stayed back for practice. “We trained in the parade ground of Bombay. The grass there was grown long to make the ground heavy, like it would be in England,” says Rajput.

Finally, the team, with Kishen Lal as captain and the brilliant K.D. Singh Babu as vice-captain, took the Air India flight Mogul Princess to London on July 13 and were put up in Richmond Park. “We were received in the Olympic village along with the US team,” recalls Claudius.

The team practised at the Indian Gymkhana grounds and was free to roam the city. “Our Olympic passes meant we did not have to pay on the buses. We could see the destruction all round, reminiscent of the World War bombings. Yet the English spirits were high. The Olympics were a diversion after the horrors of the war,” says Rajput.

|

| From Datt’s scrapbook: Jaswant Singh Rajput shows off his Olympic gold. (Sayantan Ghosh) |

The war had left its imprint on other areas. “There was shortage of items like chocolates and eggs. But the Games organisers ensured that we had everything. Imagine the sacrifice of the public! I used to give away my chocolates to the kids who came for autographs,” says Datt.

Cuisines of all the continents were available in the Games kitchen. But all countries tried their best to reduce the burden on the hosts of what has come to be called the Austerity Games. “India brought rice, flour and spices along with a cook in the ship,” recalls Rajput.

Though players mixed freely in the village, a wall had come up between India and Pakistan. “The Pakistani players were told not to mix with us,” says Datt. When he finally came face to face with old friend Shah Rukh, he was crushed to sense a lack of warmth.

There was also some bitterness when the Indians were told to shift from Richmond Park to an empty school in the suburban Pinner on July 23, with just six days to go for the opening, as reported by Anandabazar Patrika on July 21. Though some reports suspect that the quarters were being freed for Western nations who reached late, Claudius has a different take. “Our wrestlers were dirtying the toilet. Others complained.”

The Games begin

It was the first time India was marching under its own flag at the Olympic Games and for Claudius the high point of the tour remains the opening ceremony. “As defending champions, we led the Indian squad into the Wembley stadium. With a standing ovation from the crowd of 20,000, I felt as if I was transported to heaven.” This was the first time he sported a turban, in accordance with the dress code. “Our centre-forward Balbir Singh helped me tie it.”

But the soccer turf of Wembley was not suited for hockey. “It had long, thin Australian grass which when rolled became like carpet. It slowed down the game as the ball became heavy,” says Rajput.

Even then, India sailed through the league matches. In the semi-finals, they faced the Netherlands. “Before the match, (Reginald) Rodriques took off Balbir’s shirt and gave it to another centre-forward (Gerald) Glacken. The rule was only those who had taken the field would be eligible for medals and Glacken had not got a game yet,” recalls Claudius. The team spirit was such that there were no hard feelings.

Against a superior opposition, the Indians felt the shortcomings of their style on the rough ground. “They played better than us. We were lucky to win (2-1),” Claudius concedes.

In the other semi-final, Pakistan, with a similar style of play, succumbed to Great Britain. “The unsuitable turf denied the hockey world of what would have been one of the finest finals ever,” rues Datt.

It rained the night before and drizzled through D-day, August 12. A worried Indian team watched Pakistan struggle in the third place play-off before they were to take the field. “We realised that the grass was so slushy that our Asian style short passes would not work. We decided to go for aerial passes,” Datt says.

The British knew that the conditions favoured them. The royal box was full in anticipation of another upset. But the change in strategy worked so well that the British were confined to their half. India won 4-0. “We could have scored more if the ground wasn’t so heavy,” Rajput says, smugly.

And there were such celebrations! “The spine still tingles at the memory,” Claudius breaks into a toothy grin. “V.K. Krishna Menon, our high commissioner, rushed in and hugged each of us,” smiles Rajput. A newspaper cutting in Datt’s meticulously preserved scrapbook reads: “...the 11 victorious players literally danced off the field to the dressing room. Their laughter and songs as they bathed could be heard right along the long tunnel leading to the field.”

Hundreds of Britons crowded outside the dressing room to get their autographs. The British captain Norman Borrett told the press: “...I did not think they were going to have such a victory on ground so unsuited to their play. But tonight showed how magnificent they are under any condition.”

Then the historic moment came — the anthem of Independent India played as the Tricolour went up. “Our flag on their soil — what more could we want?” beams Rajput. Datt loved it even more that the medals were handed over (the garlanding had not started. The solid gold pieces had no ribbons) by his Lahore college principal, who was a member of the International Hockey Federation.

|

| Leslie Claudius at his home. (Sayantan Ghosh) |

There was no cash reward for the amateur players. Instead, they were sent on a Europe tour. “We played friendlies in Germany and Czechoslovakia. Elsewhere we just toured,” recalls Rajput. Before leaving London, on August 14, the last day of the Olympics, Claudius went to the Oval to watch Don Bradman play his last innings. “He got out on the second ball. It was so disappointing,” he says, referring to a historic moment in another sport.

Finally in September, the team boarded MV Circassia for the voyage home. “We were received by our federation president Naval Tata at the India Gate and taken to Taj Mahal hotel for a party,” says Rajput. A reception at Rashtrapati Bhavan followed.

Heroes: here and now

Other than the three men and their memories, one solitary gold medal remains in the city of that triumph. It is with Rajput.

Claudius, the most decorated hockey player in history with three golds and a silver, has lost all his golds. “It was all in that glass cabinet. Someone came to polish it and...” he points and sighs. He has heard that an Underground station would be named after him along with other Olympic heroes in London. “I am waiting to see the picture in the paper,” says the 85-year-old who still goes out for cards and drinks on Friday afternoons. His speech slurs but he remains his jovial self.

Datt gave away his medal when Nehru appealed to the nation for help during the Chinese aggression. Both he and Rajput lead solitary lives — Datt in a single-room Bypass apartment in south Calcutta, his teammate in a run-down house off Ripon Street, not far from Claudius’s rented flat. At 85, Datt’s vision has dimmed but Rajput, 83, remains sprightly. “Thanks to my vegetarian diet, I am still the fittest,” he grins.

Ask them about the prospects of the current hockey team — they met the captain Bharat Chetri recently — and they sound pragmatic. London dreams, they know, carry a single dateline: August 1948.