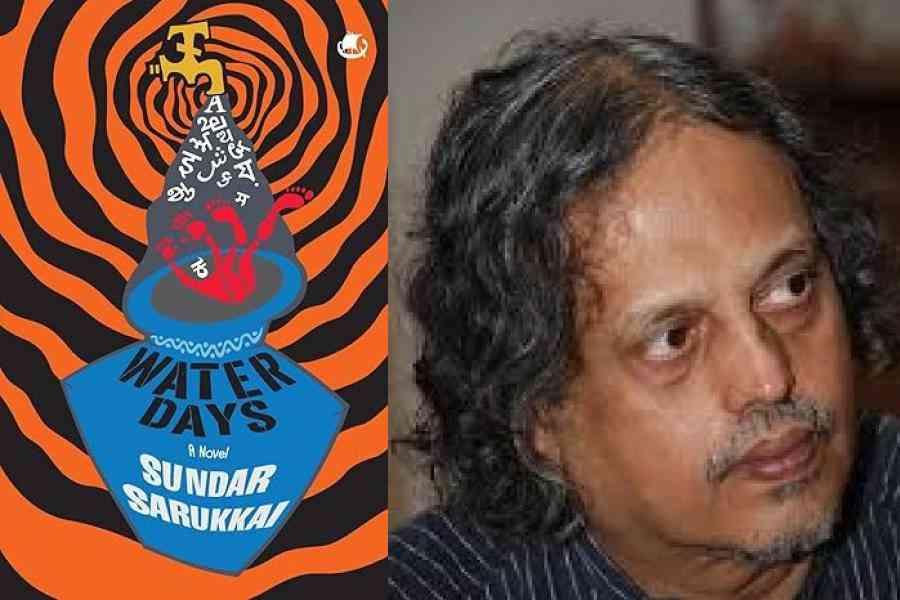

In Water Days, philosopher and writer Sundar Sarukkai offers a quiet, contemplative novel set in the shifting lanes of late ’90s Bangalore, where a young girl’s sudden death sets off ripples far beyond her home. Over the course of 13 days, readers are drawn into a neighbourhood where languages intermingle, where water taps double up as truth-tellers, and where a former security guard named Raghavendra becomes an unlikely investigator, not into a crime, but into the fraying threads of memory, grief, and community.

Known for his work in philosophy, Sarukkai returns to fiction with Water Days, his second fictional novel, with an observant eye, inviting us to consider what it means to belong, to remember, and to mourn in a city that is constantly becoming something else. Excerpts:

You’re obviously known for your academic writing, but both your novels, Following A Prayer and Water Days, are quite a departure from your usual work. What got you on the journey of writing fiction?

Before I wrote my academic books, I wrote fiction. I believe that my interest in stories influences my academic writing too, not in terms of content but perhaps in terms of flow and imagination. But fiction was much more difficult to get published since literary publication is such a clique. But my academic writing was supported by my job, and hence I was at least able to continue writing what I wanted in the domain of philosophy.

What was the initial image or thought that sparked Water Days for you?

There were a couple of inspirations. One was the difficulty in getting water in Bangalore. Even when I was growing up in a large family, getting water and storing it every day was a major chore. When I lived in Mathikere, it was the same story. And today, in many parts of Bangalore and for the majority of people who do not live in middle-class and richer areas, it is a constant struggle to obtain water every day. This is the IT capital of India! The image of collecting water under taps before dawn was a lovely image, and on those days that I have collected water, it was magical at times in the darkness of an always uneasy city. The second catalyst was my interest in detective novels and the search for a cultural expression of such stories in our cultural backyards.

The novel gives space to multiple voices, especially working-class women, whose conversations at the taps form an oral archive of the neighbourhood. The multiplicities and forms of voice in a rapidly urbanising country is, in many ways, what the book focusses on. What are your thoughts on that, and how did you go about capturing that voice?

This is particularly true of Bangalore. For long, it has been a city that has struggled with the question of its language. For various reasons, people of different languages have inhabited this place and made it their own. A dominant interest for me is the way we relate to each other. This drives my interest in anthropology and sociology, not as academic disciplines alone but as a record of our lives and communities. But as far as writing this story was concerned, my fundamental question was about the language of their stories.

When they speak in different languages, when they inhabit different imaginary worlds, what should the language of the novel be? That made me think more deeply about the language of a city. So I began with the question, does a city have a mother tongue? Given the multiplicity not just of different languages but also of dialects, what does it mean to say that regional language writing captures authenticity in a way that English does not? That is a question that interests me enormously, given that my enduring interest has been in the philosophy of language, particularly the relation between language and reality. So, it was not just enough to capture the cadences of these multiple voices but also to play with English to reproduce these multiplicities.

Producing new forms of expressions, paying attention to the way sounds from other languages are produced in English, using language not as a medium to communicate but as a felt experience... these are some of the ways in which I attempted to capture these voices.

The novel is rooted in Bangalore on the cusp of transformation. What aspects of that transition — both material and linguistic — were most important for you to capture?

Most important was the dynamics of the city, how a city changes. But a city changes without most of us having any say in it. We conform to the changes and do not cause them. We reorder our lives to whatever changes are imposed upon us in a city. Bangalore changed rapidly due to the actions of a few people, a small business class, and politicians who supported them. None of it was planned, none of it took note of what a city wanted. Bangalore, like many Indian cities, grew not as a unified imagination but as a collection of independent areas that spurted new shapes and forms. Bangalore is not an imagined city but an accident of a series of arbitrary actions.

This novel is not about capturing all the material changes in Bangalore. But it is able to exhibit these changes by listening closely to a small community of people, by minutely following their actions, and through the metaphor of a particular problem — that of the girl’s death — in their midst. The way her death is dealt with, the way we act without agency so often, dictated by the invisible force of the social that moulds our behaviour — they are all not just about the girl and what follows, but about the city itself. It is the city’s death that we are unable to mourn. It is the city that remains a stranger to all of us. That angst, that feeling of inevitability, is what I wanted to capture.

The book begins with death. To you, what does mourning mean in an urban context where people live stacked together, but may know very little about one another?

The question of what urban mourning could mean is itself an interesting question. In today’s digital world, even within families, people live their lives around their phones without knowing about one another. But urban deaths do have a role to play, one that is an important function of society in general. It is that they offer a mirror to ourselves more than produce empathy for others.

Seeing death on a street where the neighbours don’t know each other reminds every one of them on the streets that they too are mortal. Mourning is connected with loss and in a world where entertainment and information bits keep piling up one second after the next, the time to mourn others is really not there. So we have to create new urban rituals for forcing people to enter into spaces of mourning, including mourning produced by political, caste, gender and religious violence. This would mean learning to mourn not just for individuals but larger subjugated groups caught in the matrix of a city.

How do you feel your role — as a philosopher turned novelist — has evolved through works like Water Days?

I really don’t know! I like to write. I have written academic books, yes, but also plays and a children’s book. I write for newspapers and for different kinds of groups that I engage with. Actually, I don’t know what the impact of my two novels will be on my teaching practice. But writing novels allows me to do things with language that I can’t in the other forms. I also know that more people have read these novels in a shorter time frame than my academic books. And there is more of a public discussion of them compared to the philosophical books. Commercial literary culture in India has a public face. More books get reviewed, and there are literary festivals, and so on, where they can be presented. Academic books have very little public face and little readership.

Our newspapers don’t review a vast majority of good academic books. There is an easy consumption of literature, and this is tied to various cliques that operate literary festivals and other such groups that push books. I write novels because I have a great drive within me to write them. I hope people who read them will enjoy them as emotional stories that provoke them into understanding themselves and the world around them through new perspectives.