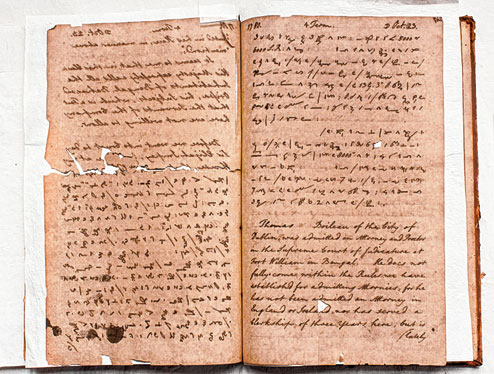

At the Bar Library of Calcutta there are preserved, as we all know, the notebooks kept by Justice Hyde during his long term of office (1774-1796), as Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court. There are no less than 73 volumes; 14 of rough notes dating from 1780 to 1794, and 59 in fair copy dating from 1775 to 1796. It may perhaps, have been the case that Hyde was at times an exceedingly misguided and obdurate person - his chief made not a few complaints as to his conduct on the Bench - but no one can study these notes without forming the highest opinion as to the writer's personal integrity, and, above all, his extraordinary diligence as a public servant.

This is, word for word, the first paragraph of Walter K. Firminger's essay entitled, Selection from the Note Books of Justice John Hyde, which was published in Bengal Past & Present (January-March 1909). The notebook was already in such a friable condition at that date that Firminger did not dare open it under a fan. As he added: "...but on the whole, it must be said that if this rich mine of historical evidence cannot be worked soon and speedily, the opportunity is to be regarded as lost for ever."

John Hyde (c.1737-1796) wanted to have his notes "correctly and handsomely" printed in England, but he died in India when Sir Robert Chambers (Puisne Judge from 1774-1791 and Chief Justice from September 1791 to August 8, 1798, when he resigned) took charge of them. The notes changed hands and ultimately came into the custody of the Supreme Court in Calcutta. Hyde was aware "though I do not suppose that they would be books that many persons would read, but conceive it may be of some public utility..."

Hyde's notes still have not seen light of day, but the notebook, which is with the Victoria Memorial Hall, has been digitised in its entirety by the institution. The papers had become brittle and they were lying in the Bar Library of Calcutta High Court. Nisith Ranjan Ray, then secretary and curator of the institution, had brought them over to Victoria Memorial. Actually, there are 74 volumes of Hyde's reports and notes, and all these have been digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records of Jadavpur University. The actual work was done over nine months by a team of three - Kawshik Ananda Kirtaniya, Amritesh Biswas and Smita Khator. Jayanta Sengupta, secretary and curator, Victoria Memorial Hall, supervised the project, and the coordinator was Gholam Nabi, head, documentation and photo unit. A microfilm of the papers exists at the National Library, but it is incomplete, said Sengupta.

The papers will be transcribed but the marginilia are of vital importance, and an attempt will be made to crack these too. What makes transcription particularly difficult is Hyde's use of 18th century shorthand ("an antiquated system of shorthand," according to Firminger), and a Fulbright scholar is trying to decipher this. The aim of the project is to make the papers accessible to scholars, and there are long-term plans to publish a book, said Sengupta. The sub-committee on academic research and publication under the board of trustees of the Victoria Memorial Hall has decided that a scholar will be appointed to make a selection of the papers (along with annotations) which will be turned into CDs, and these extracts will be available for sale. The Hall gets enquiries about the Hyde papers from legal historians. Earlier, only 15 to 20 pages had been digitised and not in high resolution.

S.C. Nandi, who had studied the papers and written an article on it in Bengal Past and Present (January-June 1978) suggests that the entire set of papers should be printed "as it is." Nandi in his article had refuted some of the points raised by Firminger, beginning with the number of existing volumes (74, according to Nandi). Having examined the papers, Nandi came to the conclusion that the notes concern only the sessions trial of Joseph Fowke, Maharaja Nandakumar and Roy Radhacharan for a conspiracy against Richard Barwell, Esq, and have nothing to do with the famous trial of Nandakumar, as Firminger had surmised. Moreover, "what goes by the name of 'rough notes' are 15 in number (not 14). The period covered is from 1780 to 1796 (not 1794)...It was also quite clear that it was Sir Robert Chambers, the Chief Justice, who continued to maintain the notes. Volumes 51 to 59 can therefore be considered as post-Hyde notes, kept mainly by Chambers and possibly by the other Judges of the Supreme Court, as there is quite a variety of writing." As Nandi himself comments: "Opinions are bound to vary from person to person."

Nandi continued: "The notes of Justice John Hyde are undoubtedly a gold mine of not only historical and legal information but also provide source material for economic and social knowledge about the period. The reading of these notes also carries with them a feeling of frustration, as many of the legal suits are incomplete and unrecorded."

Nandi summed up: "Even to read a simple statement of facts by a witness in 1792 is to conjure the vision of a different world altogether: 'I came thro' the paddy fields into the Chowringhy road.' ...All the important characters of the period will be found in the note books of Hyde."

Pradip Sinha had been commissioned to research and publish these papers in 2005, but, as Sengupta says, he probably could not "flesh out his editorial introduction because of his untimely death".