Growing up in the India of the 1970s, I had ambivalent feelings towards America. I admired some of their writers (Ernest Hemingway was a particular favourite) and adored the music of Bob Dylan and Mississippi John Hurt. On the other hand, I was just about old enough to remember — and never forget — how Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger had so energetically supported Pakistan against India (and Bangladesh) in the war of 1971.

In 1980 I moved to Calcutta, and my ambivalence turned to outright hostility. Under the influence of my Marxist teachers, I became actively anti-American. I expressed private and public disdain for their brashness, their gross commercialism, their imperialist (mis)adventures in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Left to myself I would never have entered the United States of America. However, in 1985, my wife, Sujata, a recent graduate of the National Institute of Design, got a scholarship to do a Masters at Yale University. I could not stand in her way — the Yale graphic design department was reckoned to be the best in the world — but had to find a way to join her. Fortunately, I had come to know the historian, Uma Dasgupta, who then held a senior position at the United States Educational Foundation for India. With Umadi’s advice and assistance, I applied for a visiting lecturership at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, which — to my surprise — actually came through.

Sujata left for Yale in August 1985. In November of the same year, this confirmed anti-American found himself outside the US Consulate on Ho Chi Minh Sarani. The counter opened at 8.30 am — I was there at seven, partly out of anxiety, and partly because when I accompanied Sujata for her visa interview in Madras there was a long line outside the American Consulate there, curving right around Mount Road all the way to the Thousand Lights Mosque. But here there was just one person ahead of me in the queue. It struck me that the Tamils were not at all anti-American, and produced engineers in far greater numbers than the Bengalis. Besides, I was due to teach from the spring term, when fewer Indians sought to go West than in the autumn.

I reached Yale on January 2, 1986, and spent the next year-and-a-half expanding my mind, teaching as well as learning from my students. In retrospect, I am very glad I went to America when I did. Since I had done a PhD already, I was sure of the ground on which I stood. Meeting young Indian historians who had studied in America, I was immediately struck by how driven by fashion their work was. In the wake of Edward Said’s Orientalism, post-colonialism and Cultural Studies were all the rage. In the two disciplines I knew best, history and social anthropology, sustained empirical research was not encouraged any more. Rather than spend months in the field or in the archive, these acolytes of Edward Said preferred to take out texts by dead white males from the nearest library and scrutinise them for their departures from what then passed for ‘radical politics’.

The Indians of my generation who had come to America to study and teach had largely done so for personal advancement. But it was not so much for their opportunism that I shunned them; it was more that their intellectual concerns were not mine. The scholars I was attracted to worked on one or both of my subject fields — the environment and social protest — albeit in cultures and contexts other than my own. At Yale itself, I had long conversations with the environmental sociologist, William Burch, the environmental historian, William Cronon, and the ecological anthropologist, Timothy Weiskel. A senior Yale scholar whom I spoke with regularly was James Scott, who had just published what in my view remains the best of his many books, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. Outside Yale, I made contact with the comparativist, Michael Adas, at Rutgers, the sociologist, Louise Fortmann, at Berkeley, and the doyen of American environmental history, Donald Worster, then teaching at Brandeis.

These scholars had worked on Africa, Southeast Asia and North America, using techniques and disciplines different from the ones to which I was accustomed. And, unlike established academics in Calcutta or Delhi, these American professors were refreshingly free of hierarchy. Though much older than myself, they were happy to be called by their first names, and happy to have their ideas critically assessed too. Meeting these scholars, and reading their works, expanded my intellectual horizons and enlarged my intellectual ambitions. Like them, I wanted to publish my PhD as a book, and get on to work on a second book, and then a third. Too many Indians I knew had written a fine first book and then rested on their laurels. On the other hand, Adas, Scott and Worster all had an impressive oeuvre, notable for its depth and its diversity. That was the model I wished to follow when I came back home.

One reason Sujata and I enjoyed Yale so much is that we knew that when she graduated, we would go back to our homeland. The other Indians at Yale were all desperate to stay on — which meant that they were anxious to take the right courses to get the right job that might get them a work visa and in time a Green Card. Because we had no such anxieties, we could take full advantage of all that this great university had to offer. And we made some close American friends, with whom we are still in touch.

In the four decades since we returned from New Haven, I have been back to the US many times. Most trips have been short — a week or two — but occasionally I have spent longer spells at universities on the East and West Coasts. I have the happiest memories of a semester spent at the University of California at Berkeley, where — at this great public university — the students were as intellectually sharp yet of far more diverse backgrounds than at Yale or Stanford. I was teaching a course on Mahatma Gandhi, and the interest shown in the man and his legacy by my Burmese, Jewish and African-American students convinced me that it would be worth my while to spend the next decade (and more) researching and writing about Gandhi.

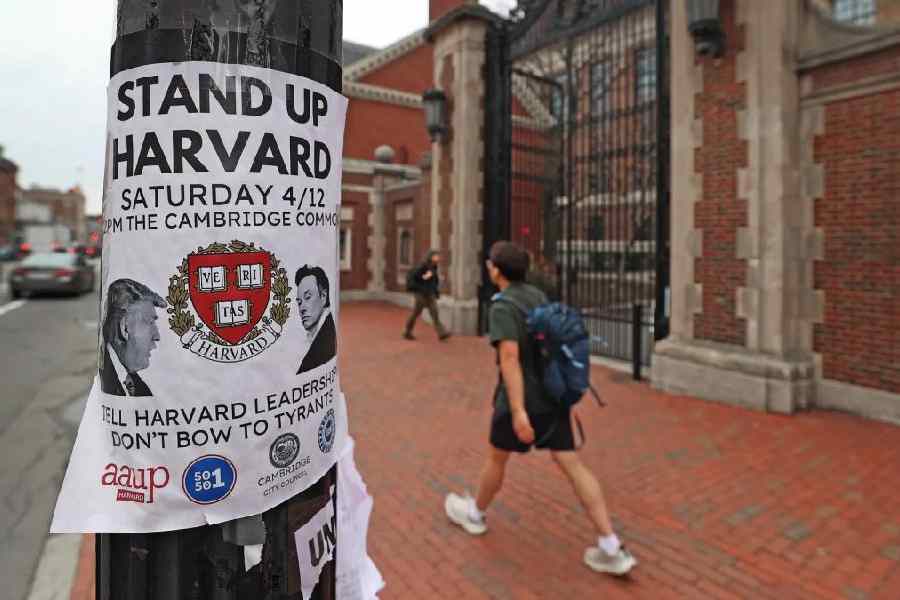

I was myself entirely educated in India, and have spent the vast bulk of my life living and working in India. Yet, I owe an enormous debt to the scholars and students I have spent time with in America. And to the libraries and archives in that country too, which often contain priceless documents on the history of India unavailable in my homeland. I therefore feel a deep sense of anguish and anger at what Donald Trump is doing to wreck the American university system. Whether conducted out of ideology or personal spite, Trump’s campaign is causing enormous damage to a country he leads and claims to love.

It is true that in recent decades, the American higher education system has committed some self-goals. Of these, two stand out — the capitulation to identity politics, which has greatly inhibited free discussion and constructive debate on campuses; and the decision to do away with the retirement age, so that scholars in their eighties and nineties are still there to teach (smaller and smaller) classes, maintain large offices, and retain voting rights over future appointments. That said, most of the best universities in the world are still in the US. By educating and influencing scholars from all over the world, they have enormously enhanced the country’s soft power. And, perhaps more pertinently, they have nourished an apparently unending stream of scientific creativity, which has played an incalculable role in making America the most economically and technologically advanced country in the world.

Before I went to Yale in 1986, I had been for some time a critic of American foreign policy. In the years since, I have retained my strong scepticism of its government’s intentions abroad. All through my life, the foreign policy of the US has been characterised by a mixture of arrogance and hypocrisy. Yet its universities are another matter altogether. They are an adornment to humanity, and motivated or ignorant attacks on them should be mourned by thinking people of all nationalities.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in