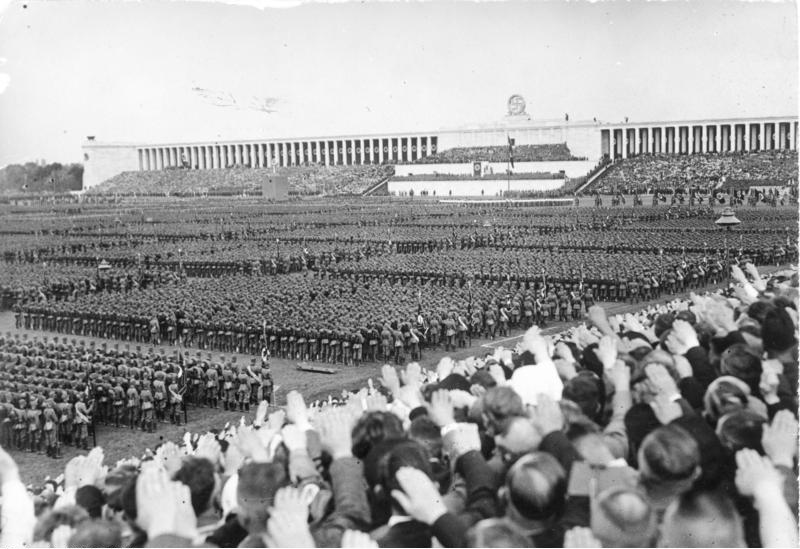

Fifty-two years ago, as protests against the Vietnam war were snowballing, the counter-culture gaining traction, young people rebelling against the roles assigned to them in matters to do with gender, class, race, sexuality and so on, a time often summed up as the age of sex, and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, a young history teacher in a high school in California was trying to explain to his 15-year-old students just how it was that perfectly normal, ordinary Germans were able to become complicit with, and then deny their involvement in, the rise of National Socialism in 1920s and ’30s Germany. Finding himself failing to get through to his students at the intellectual level, Ron Jones decided to run an exercise to show them just how such a thing became possible. He invented a ‘movement’ called The Third Wave which, he told his students on a Monday, was predicated on discipline. In Jones’s own words, in a short story he self-published in 1976, which is still the fullest account of his experiment, “I lectured about the beauty of discipline. How an athlete feels [after] having worked hard and regularly to be successful at a sport. How a ballet dancer or painter works hard to perfect a movement. The dedicated patience of a scientist in pursuit of an Idea. It’s discipline. That self training. Control. The power of the will. The exchange of physical hardships for superior mental and physical facilities. The ultimate triumph.”

But instead of merely talking about it, Jones made his students enact it — by making them sit in a rigid upright position, by following rules about how they should ask, or respond to, questions in the classroom and so on — and found, somewhat to his surprise, that the efficacy of his teaching had improved dramatically through these few simple measures. On Tuesday, he gave them a salute — with the cupped right hand swinging across the chest — and wrote two mottoes on the blackboard, “Strength Through Discipline”, “Strength Through Community”, which he then spoke on, telling them how “Community is that bond between individuals who work and struggle together. It’s raising a barn with your neighbours; it’s feeling that you are a part of something beyond yourself, a movement, a team... a cause.” He also had the class chant the mottoes, first in pairs and then, gradually, in unison, as members of one unified community.

By Wednesday, the school was agog with news of this new movement to which only a select few students seemed to have been admitted. On the same day, Jones issued ‘membership cards’ to every student who wanted to continue with the experiment — not one student opted out. In fact, several students from other classes joined the movement. Jones marked three of the cards with an ‘X’ and told the students whom he gave these special cards to that they had been specially selected to report on students who were not following the rules of The Third Wave. His lecture that day was on the importance of action and how discipline and community were meaningless without action. “I instructed students in a simple procedure for initiating new members. It went like this. A new member had only to be recommended by an existing member and issued a card by me. Upon receiving this card the new member had to demonstrate knowledge of our rules and pledge obedience to them. My announcement unleashed a fervour.”

Everyone in Jones’s school — Cubberley High School in Palo Alto — from the principal to the librarian to the cook to his teaching colleagues, was infected by Third Wave fever by the fourth day; and Jones, by now deeply apprehensive of the monster he seemed to have unwittingly unleashed, was beginning to look for a way to bring his experiment to a close. In near desperation, he hit upon the idea of telling his students that a special rally would take place at noon the following day, where a presidential candidate would announce the formation of a Third Wave Youth Programme, the first step towards a new beginning for the United States of America, where members of The Third Wave would form the vanguard. The response was beyond Jones’s wildest imaginings.

On Friday, the final day of the experiment, The Third Wave students were ushered into the school auditorium to listen to the presidential candidate address the nation on television. The tension in the packed hall was electric; everyone seemed to be holding their breath. At Jones’s command, the students chanted The Third Wave mottoes and gave the Wave salute for the benefit of the press and photographers (friends of Jones, dressed up to play these roles) present. At five-past-noon, Jones turned off the hall lights and turned on the television — the air of expectancy was palpable. “The only light in the room was coming from the television and it played against the faces in the room. Eyes strained and pulled at the light but the pattern didn’t change. The room stayed deadly still. Waiting. There was a mental tug of war between the people in the room and the television. The television won. The white glow of the test pattern didn’t snap into the vision of a political candidate. It just whined on. Still the viewers persisted... Anticipation turned to anxiety and then to frustration.” Seizing the moment, Jones told his by now restive audience, “There is no leader! There is no such thing as a national youth movement called TheThird Wave. You have been used. Manipulated. Shoved by your own desires into the place you now find yourself. You are no better or worse than the German Nazis we have been studying.” He went on: “You thought that you were the elect. That you were better than those outside this room. You bargained your freedom for the comfort of discipline and superiority. You chose to accept that group’s will and the big lie over your own conviction. Oh, you think to yourself that you were just going along for the fun. That you could extricate yourself at any moment. But where were you heading? How far would you have gone?” So saying, Jones then screened a documentary on Nazi Germany and ended by announcing that what his students had experienced over the course of the school week was the answer to the question he had tried, but initially failed, to answer, “How could the German soldier, teacher, railroad conductor, nurse, tax collector, the average citizen, claim at the end of the Third Reich that they knew nothing of what was going on? How can a people be a part of something and then claim at the demise that they were not really involved? What causes people to blank out their own history?” Jones ends his 1976 account by saying that none of the 200-odd students who were part of The Third Wave ever admitted to having attended that final Friday rally.

The Third Wave gave birth to an acclaimed 1981 American made-for-television film, The Wave, a novelization by the same name in the same year which, in turn, led to the making of an award-winning German film, Die Welle (The Wave) in 2008. In 2010, a documentary, Lesson Plan, produced by one of Jones’s students, who was part of the Third Wave experiment in 1967, also received critical acclaim.

As we observe the rise of messianic authoritarian leaders across the globe and the apparent willingness of large sections of people to follow them in forming disciplined, exclusive, patriotic, nationalistic communities, a look back at Ron Jones and his experiment might yet yield some valuable insights into our lives and times.