When I first came across Diego Maradona in a packed pub in Central London on a hot June day in 1986, I ran away. That day, I was walking around the city with two desi women friends, neither of whom had the slightest interest in sport. I myself had only recently, in 1983, rekindled my own passion for cricket, having been in the America zone for a few years before that. In June 1986, I was returning again from the United States of America, which was not only a cricket-free but then also a football-free cosmos, and had stopped by in London to hang out with one of the aforementioned women who was a close friend. During my stay, our concentration was on reading postmodern tracts by and about Foucault, Derrida, Barthes et al, and then finding a series of congenial drinking spots in which to argue about them loudly. In between, we would stumble into cinemas to watch a few films. Therefore, I was only fuzzily aware that something like the football World Cup was going on in Mexico.

On this day, however, the match in Mexico City had caught my attention. It was a quarter-final between England and Argentina, two countries which had been at war just a few years previously. In 1982, coming back from the US to India, I had also broken journey in London to see another friend. The Falklands War had just ended and I was narrowly dissuaded by the London friend from bringing along and wearing one of the Viva Las Malvinas t-shirts, which were widely available for purchase on New York’s streets. The friend’s dissuasion surely saved me from grievous bodily harm, for the t-shirt was a provocation to any British nationalist: Las Malvinas was what Argentina called the Falkland Islands; the phrase was a war cry against what the Argentinians saw as illegal British occupation. In 1986, even after four years, there was a decent quantum of bad blood between Thatcher’s England and post-dictatorship Argentina, and this quarter-final promised more than just football.

My friends, however, were a determined pair, and no piffling football was going to come in the way of us starting the day’s serious drinking. And no, they were certainly not going into any pub filled with white men shouting at TV screens. Nevertheless, while passing one of these pubs I heard a huge roar and decided to duck in to see what was happening. My friends agreed with bad grace to wait outside, instructing me to hurry up. I entered the pub just in time to see what would become probably the most replayed segment of sporting footage ever: a blue and white striped cannonball rammed through a clutch of white-clad defenders and rose to meet the ball in front of goal, as the man jumped his hands were in the hands-up position near his head, the ball rocketed into goal, the England players started beating their wrists and shouting at the referee who was unmoved, the goal stood — Argentina 1:England 0. At each replay of the ‘goal’, I could hear glasses smash in the pub, someone punched something wooden and the wood gave way, in the jostle of bodies near the door someone noticed me, a thin, brown-skinned man with longish black hair. I then felt several eyes train themselves upon me.

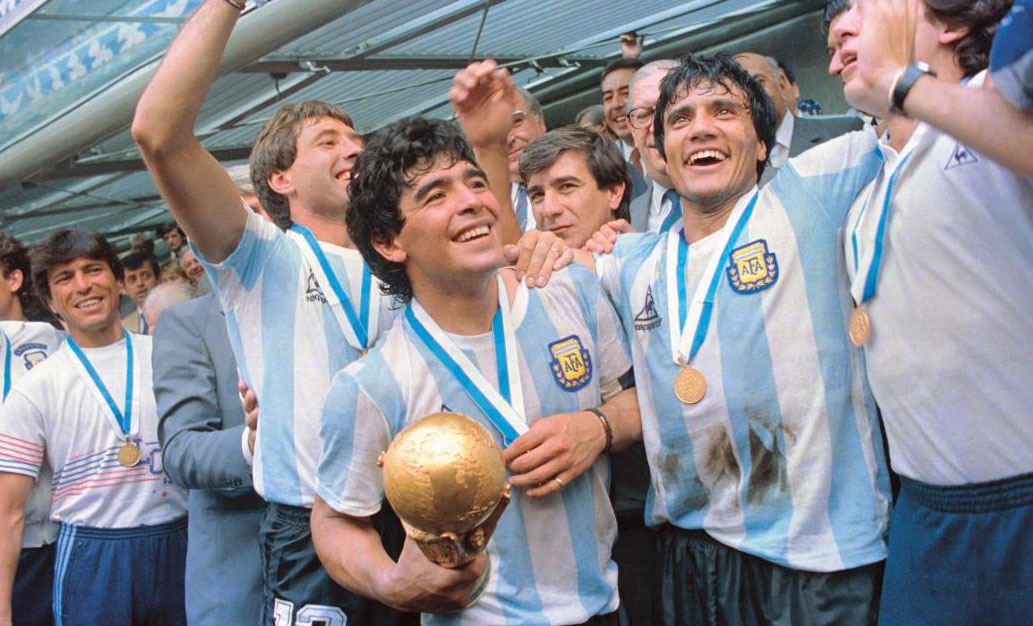

Maradona celebrates his second goal against England during the 1986 Fifa World Cup. (Wikimedia Commons)

I wanted to watch the replay once more, I wanted to see more of this phenomenon I’d vaguely heard about, this Maradona who was supposed to be Pele’s equal. But some life-preserving instinct kicked in, I realized I did not look un-Argentinian enough, and I backed out of the pub and walked away very fast, my friends trotting after me, wondering what had happened. I was nowhere near a TV when, just four minutes later, Maradona slalomed through the English players to score one of his most sublime goals, this time with nothing but his feet. I did, however, watch everything on the news that night, and again and again since then. I remember Maradona inciting these strange contradictory feelings inside me — fascination, awe, elation, all mixed with a kind of repulsion and unease that I couldn’t quite explain.

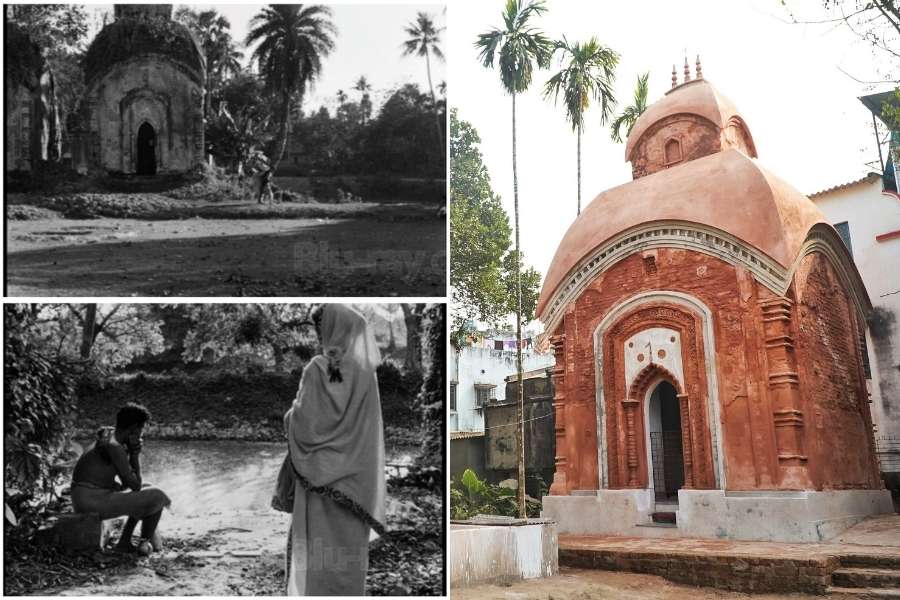

When the title of Asif Kapadia’s recently released film comes on screen, there seems to be an invisible forward slash dividing Diego and Maradona. Indeed the whole film explores the schism between the angel and the devil residing in this one man, the indescribable talent and the street-thug’s ferality, the loving son and brother and the monstrous egotist, the supremely intelligent footballer and the unbelievably stupid celebrity. As he has done with Senna and Amy, (about Ayrton Senna, the racing car driver, and Amy Winehouse, the singer), for Diego Maradona, Kapadia has gathered an ocean of archive footage and delved deep into it, gathering both basic building blocks and gems with which to construct the story. In fact, in the 2 hour 10 minutes of the film, Kapadia has himself filmed perhaps one shot — a slow aerial sweep over night-time Naples — with everything else being archival footage, from grainy, early 1960s, black-and-white film of Villa Fiorito, a shantytown at the edge of Buenos Aires, where Maradona grew up (a place that very much resembles slums in Calcutta or Bombay), to home videos on to news footage of gangland murders in 1980s Naples. The growing ubiquitousness of the VHS video camera in the 1980s is what makes Kapadia’s film, because along with Maradona’s rising fame comes the deeper and deeper insertion of attention, both wanted and unwanted, licensed and unlicensed.

If anything, the football itself is but an abhushan of the film, the various moments from Maradona’s playing career adorn the film even as they help provide the impetus to the unfolding of a great, grungy, modern tragedy. The narrative isn’t linear. The film begins with raking the viewer with different aspects of the legendary career: Diego Armando Maradona playing, DAM driving to the massive Napoli stadium, DAM as a teenager (looking spookily like a young Sachin Tendulkar, or vice versa), receiving a trophy and so on. The concentration of the film is Maradona’s time at Napoli when he takes the near-relegation team to the top of the Italian League and plants it there. This time also spans the two World Cups where Maradona is at his best, 1986 and 1990. This is also the time of his many affairs, his dalliance with the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia, his growing ensnarement by cocaine and then the final rejection by the Italian and, more crucially, Neapolitan fans when his Argentina sends Italy out of the World Cup in the semi-final at Naples.

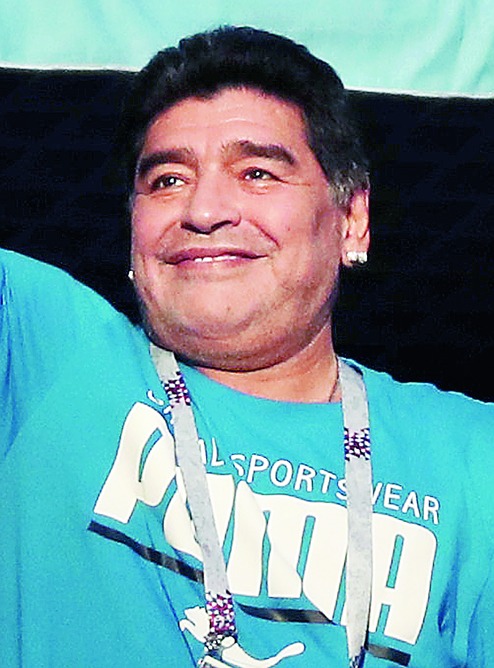

Asif Kapadia's film on Maradona explores the schism between the angel and the devil residing in this one man, the indescribable talent and the street-thug’s ferality, the loving son and the monstrous egotist, the supremely intelligent footballer and the unbelievably stupid celebrity (Shutterstock)

It is no surprise that Maradona would have been the most documented and most video-filmed celebrity of his time. The admixture between the monumentally egotistic self-regard and the almost pornographic fascination with everything about DAM gives us some amazing moments: Maradona when training alone with his physio; Maradona receiving injections in his back; Maradona’s heel being cut open; Maradona and team-mates in the post-triumph dressing rooms, almost naked, sweat and champagne flying into the lens; Maradona’s daughter at about two being taught by her dad to say ‘____ you, Milan! ____ you Juve! We are going to kill them all’; Maradona distraught in court as the Italian prosecution closes around him for various misdemeanours, ranging from drug use to tax evasion.

In the portrait of this messy, garish, sungun-lit circus of a life, Kapadia nevertheless displays a strict minimalism and narrative rigour. The period of DAM’s long fall from grace is not dwelt upon, we do not see him in the disastrous 1994 World Cup, we do not see him hobnobbing with Fidel Castro. At the end, we cut straight to recent times, to the hulking, hobbling, square shipwreck of a man in his late 50s, thinking back to what was, what could have been, and how he arrived where he is.

In that fleeting, crazy moment in the London pub in 1986, I could not have known that I was witnessing but one key moment of the epic that was unfolding, but I did realize I was watching something and someone special, a genius who would trouble the world in various ways before he was finally done.