‘Et tu SBT?’ These must be the words on the mind of the Bard upon hearing the plan of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust to ‘decolonise’ his legacy. Decolonisation, admittedly, has become a buzzword in recent times, especially after the Black Lives Matter movement, with fraternities, such as academics and students, lodging angry protests against the (mis)deeds of the Empire, including the enslavement, brutalisation, and exploitation of colonised peoples. The desire to re-examine William Shakespeare within the context of colonialism and race is rooted in this sensibility. But such an effort risks inadvertently reinforcing the very structures it seeks to dismantle. Shakespeare’s genius lies in the multiplicity of interpretations that his works can support — think of Yaël Farber’s SeZaR in which he adapted Julius Caesar to reflect a uniquely South African political struggle or, closer home, of Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider that made it seem that Kashmir, its politics and struggles, could be the ideal setting for the play. Any attempt to constrict Shakespeare to the narrow confines of contemporary ideological battles pertaining to race, gender, and colonialism could diminish the richness and the vitality integral to his work.

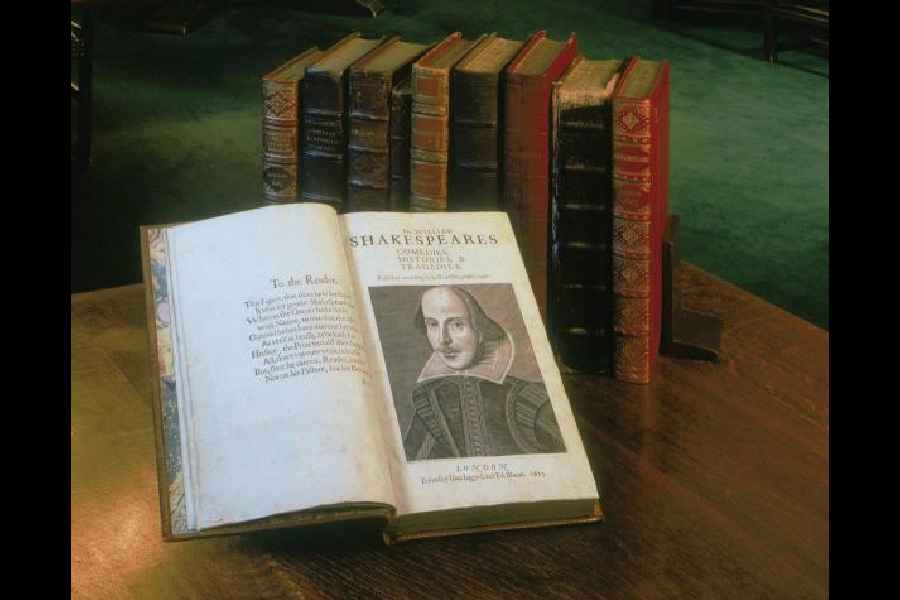

What is even more absurd is the historical incongruity of this quixotic pursuit. Shakespeare was born in 1564 and died in 1616 when the so-called Empire did not exist and England ruled virtually nothing other than itself — in fact, the Mughals had more colonies than the British when the Bard lived and worked. It is true that Shakespeare’s writing has had an appeal for versatile groups, often with dubious motives. There is thus nothing wrong with endeavours to examine the ways in which Shakespeare has been appropriated by, say, racists or colonisers: The Tempest, for example, has been used to legitimise the West’s civilisational project. But to suggest that calling Shakespeare’s ideas “universal” is to privilege a 'Eurocentric world view', as the SBT has done, is to miss both the woods and the trees and focus on the lumberjacks. The argument conflates the imposition of Western power with ideas that might have emerged from within the Western tradition but that have been essential in challenging the edifice of this very power globally. Long before decolonisation acquired intellectual heft, cultures around the world adapted Shakespeare to challenge injustice and speak truth to power.

The greatness of Shakespeare, as argued by James Baldwin — among the foremost African-American authors and civil rights activists — lies in his desire “to defeat all labels and complicate all battles”. Decolonising the Bard’s works is undoubtedly one such complicated battle. While Othello does include some racial prejudices, how many other works of literature from the early 17th century could claim to have a Black man as the protagonist? Shakespeare’s gift was to give all of his characters — even Shylock — depth, humanity and psychological complexity. His work has universal appeal because his portrayal of ideas of justice as well as of human emotions, motives and the conditions that shape these are not rooted in ethnic — European — moorings: they encompass the global. The reason Shakespeare endures is that his creativity transcends racial, national and generational differences and reveals what the world has in common, rather than what divides it.