The new Superman’s trunks — I hope Lois Lane and Wonder Woman will not mind this confession — have been on my mind.

Those with an interest in the cultural evolution of the Man of Steel across the decades — this columnist is one — would remember that the classic red trunks had been got rid of by the makers of the angst-ridden, darker Superman portrayed by the actor, Henry Cavill. James Gunn, the director of the mint-new Superman flick that was released this month, has, however, made the Kryptonian wear his signature red trunks, once again, apparently to recapture the comic-book icon’s traditional look that had been jettisoned by his predecessor, Zack Snyder.

Whether Superman — correction, his creators — wants to keep or drop his trunks is not the point though. What would be of interest to admirers and analysts of this comic-book creature is the choice of the colour of his trunks. This is because Superman’s red trunks are, arguably, the only remaining symbolic relic — clue — in his costume that whisper that this much-loved extra-terrestrial had begun his career on Earth as a — you are reading this right, dear reader — left-wing, radical vigilante.

Thanks to endless references in cinema and comic series, generations of admirers of the Man of Steel think that Superman’s backstory is that of an alien with a heart of gold who dropped from the skies — quite literally — on a Kansas farm after he was flown out by his Kryptonian parents from a dying planet. Nourished by the yellow sun and earthlings, he goes on to become many things: America’s mightiest fictional hero, an emblem of American ideological values, and, in geopolitics, an instrument of US soft power as well as expansionism.

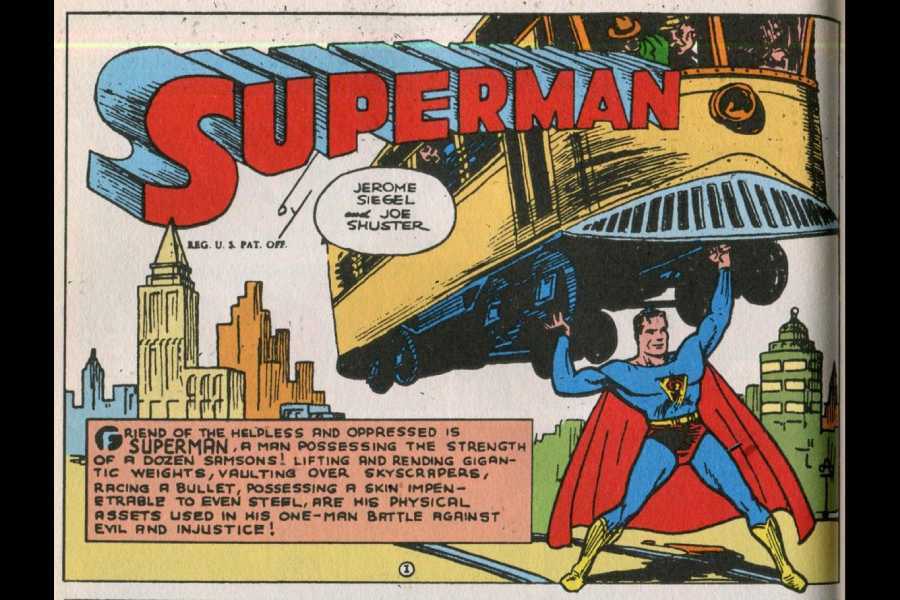

But it had all begun on a different note — as has been pointed out recently in an excellent piece in the BBC by Nicholas Barber, who argues that in contrast to being America’s Mr Nice Guy, Superman originated, in the America of the 1930s in the Action Comics magazine, as a figure who was decidedly socialist in his ideological bent and political choices and quite violent in his actions. Barber quotes Paul S. Hirsch, the author of Pulp Empire: The Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism, who calls Superman a “violent socialist”. The writer of comic books and historian, Mark Waid, goes a step further and describes Lois Lane’s lover as a “super anarchist”.

The early comic books, in fact, bear evidence of Superman’s pronounced red streaks. In the 1930s, he battled not aliens or Lex Luthor but gun racketeers, domestic abusers, an orphanage boss known for his cruelty towards children, a politician who buys a newspaper and turns it into a broadsheet for propaganda, a mine-owner playing footsie with safety standards, a real estate mogul who sabotages his rivals’ projects and so on: in other words, Superman was speaking up, in an America lacerated by the economic sufferings and moral degeneration inflicted by the Great Depression, on behalf of the subjugated aam aadmi just like a left-wing sympathiser.

It is surprising that Joe Shuster, who created Superman along with Jerry Siegel, chose a blue suit for their creation. Given his socialist leanings, Superman would have done justice to an all-red suit, trunks and all.

The sociological analysis — Barber’s article provides this — of Superman’s socialist sympathies is equally revealing. Shuster and Siegel were both immigrant Jews to America. Shuster’s parents hailed from Rotterdam; Siegel’s family had had to flee anti-Semitism in Lithuania. Their experiences of persecution and penury sharpened their progressive and liberal beliefs that they subsequently channelled into the character that they created. The possible reasons for the genesis of Comrade Clark Kent are quite instructive. America’s then incipient comic industry, an emerging axis within the US’s expanding edifice of cultural production, was peopled with the victims of a myriad forms of exclusion. Jews, immigrants, people of colour, women, social constituencies that found the doors of mainstream industries and occupations shut for them, propelled the fledgling comics industry with their creative powers and their life experiences of ostracisation. Little wonder then that the Man of Steel of the 1930s was a vigilante and an ideologue rolled into one.

So why did Superman change his spots — from red to blue?

Barber provides tantalising possibilities while answering this question. The phenomenal success of Superman as a commercial product made it impossible for him to retain his radical inclinations. He was thus tamed down — journeying, in a manner of speaking, from Left to Centre. The Second World War also brought immense patriotic fervour and consequent pressure upon America’s cultural outliers to deradicalise. Ironically, it was only by discarding empathy for the man on the street that the fraternity of artists like Shuster and Siegel was able to gain a toehold in the idea of belonging to the American mainstream. Then, in post-War America, emerged the spectre of McCarthyism, the sting of which led to Superman becoming decidedly avuncular. DC’s dubious treatment of Shuster and Siegel — the artists lost the legal battle against the company to reclaim their copyrights on Superman — may have also done its bit to transform the icon’s conscientious, pro-people heart.

This real, rarely-discussed backstory of Superman leads to some intriguing conclusions. For instance, it appears that the founding visions of our cultural icons — made and remade by the shifting tides of politics, ideology and commerce — could, in many instances, have been markedly different from what they are today. Superman’s legacy is a case in point. The values that this supposedly All American Hero fought for, literally and figuratively, in his early years — diversity, equality, inclusion, immigration — would horrify the American Establishment in the Donald Trump era. The contemporary comic book aficionado, scholarly or lay, should try and dig up more on the micro-histories and evolutionary arcs of not just Superman and his Western brethren but also their Indian peers — Bahadur, Bhokal, even ostensibly benign ones like Suppandi and Shikari Shambu. A number of surprises could await us in this endeavour.

The other issue pertains to the sad eclipse of the creator by the creation. Superman has certainly devoured not just the revealing legacies of the two men who nurtured him to life but also their struggles and ideas of justice. This is a quirk of history and ought to be acknowledged. It would not be a travesty of justice — is justice not what Superman stands for? — to suggest that Shuster and Siegel perhaps have a greater right to wear the crusader’s red cape than Superman.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in