“I am Omar al-Jmasy. I owe one shekel to a boy named Abdul Karim al-Naireb. Abdul Karim lives on Abu Nafidh Street.

I love you, my dear ones, and I hope that you will not abandon praying, reading the Qur’an and seeking forgiveness.”

*******

“Please don’t cry for me because I feel tortured when I see you cry.

I hope my clothes will be given to those in need.

My accessories should be shared between Rahaf, Sara, Judy, Lana and Batool.

My bead kits should go to Ahmad and Rahaf.

As for my monthly allowance of 50 shekels, I want half to go to Rahaf and the other half to Ahmad.

My stories and notebooks to Rahaf.

I’d like Batool to have my toys.

Lastly, please do not yell at my brother Ahmad.

Please follow these wishes.”

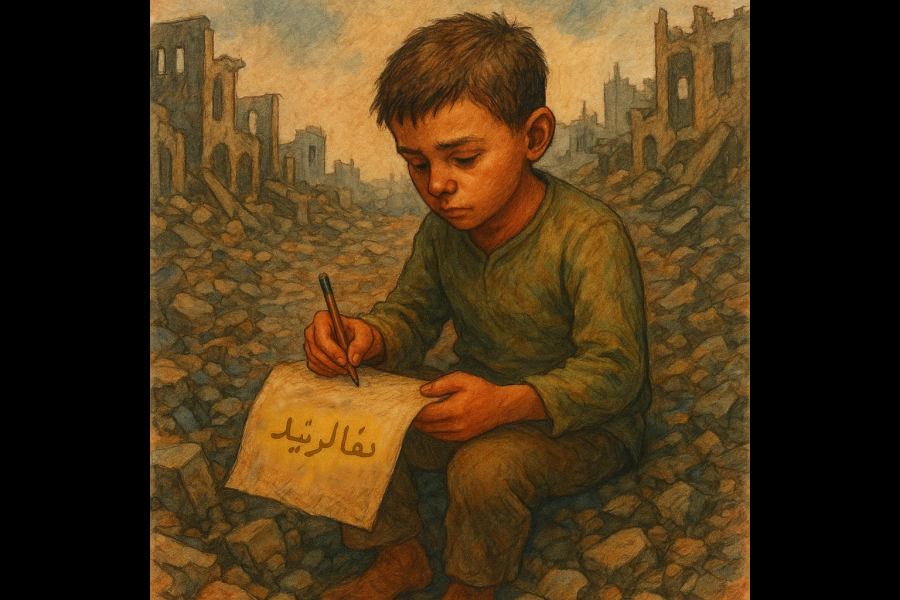

The above-mentioned declarations, as some of their lines indicate, testify to the human willingness — ability — to acknowledge the imminence of death and, consequently, renounce and, thereupon, pass on one’s material possessions. There is a particular — peculiar — historical and legal instrument, created in Ancient Greece and, then, perfected across Roman and subsequent civilisations, that enables individuals to accomplish the latter — the disbursement of belongings. This instrument is the legal will, a deed central to modern codes of inheritance.

The will, it is generally believed, is the preserve of the aged and the infirm. The members of these two constituencies, aware that they are in the twilight of their lives, are generally receptive to the idea of bequeathing their material possessions to their dependants and loved ones, usually their kin.

The wills that were cited at the beginning of this article may, on hurried reading, appear to be mundane in that they, too, demonstrate an acknowledgement of mortal effacement on the part of the testators as well as a willingness to transfer possessions — utterly meagre ones in these instances, a bead kit, paltry sums of money, a story book — to beneficiaries.

But these two wills, by no stretch of the imagination, can be attested as ordinary documents.

The first will, as reported by Al Jazeera and made evident by the text, was written by Omar al-Jmasy. Omar was 15 years old when he penned his will. He died — was killed — soon after, in an air strike last month, after Israel violated the fragile ceasefire in Gaza. Omar’s foreknowledge — not foreboding — and calm acceptance of his approaching demise, his anxiety to be free of debt, even if the debt was of one shekel, his assurance of his affection for his family speak of a dignity, a precocity, mettle — can language, any language, adequately describe Omar and what he felt while writing his will? — that are uncommon in a child as young as him.

The other will, which communicated the same kind of love and empathy for those the writer of the will was leaving behind, was written by a girl. Rasha al-Areer, Al Jazeera reported, was 10 years old when she died last year in the hellfire that has engulfed Gaza. How does one respond to, process, Rasha’s knowledge of the precarity of her young life, her generosity, or, indeed, her infantile protectiveness — nobody is to shout at her brother, Ahmad — in the face of certain death?

Two other conditions — violations — make the wills of Omar and Rasha an exception.

WillJini, a Mumbai-based web portal that assists in the writing of wills online, is of the view that the Covid pandemic has apparently prodded young, wealthy Indians to prepare their wills, thereby challenging the perception that the will is the fiefdom of the elderly. The demographic shift notwithstanding, *this, under ordinary circumstances, could not have been the time for Omar and Rasha — 15 and 10 years old, respectively — to pass on their life’s humble possessions. That act should have come at the end of a long and fulfilling life, one that the children were denied. Their wills, therefore, remain as evidence of time being stolen from the two children.

Secondly, a will, ideally, is an act of volition. But the young hands of Omar and Rasha were forced on that paper by the predations of an adversary; their premature wills thus signify duress, a compulsion, and not volition.

Israel has killed over 17,000 children in Gaza since the beginning of its “limited ground operation” in October 2023. This means that on an average, one Gazan child gets killed every 45 minutes. These, indeed, could be the grim, fecund hours for children scrawling their wills not just in Gaza but also around the world. Children and Armed Conflict, a report compiled by the special representative of the secretary-general of the United Nations, stated that the year, 2023, had witnessed a 21% spike in violence against children under 18. Some theatres of war have turned children from pawns to personnel of war. Between 2005 and 2022, an estimated 100,000 children had been enlisted as soldiers across 20 conflict-ridden nations. Some, the report states, were as young as eight or nine, among which, approximately 40% were girls. With over 70 countries engaged in armed struggles, the grotesque ritual of children having to write their own wills may no longer be an aberration. Instead, these wills, together with children’s war diaries preserved for posterity, could turn out to be of testimonial value — a barometer of depravity, if you will — for the future archivist rummaging through the debris of human civilisation.

Historically, what helped the will transcend its narrow legal contours was its purported philosophical mooring. It was once an attempt, albeit an ineffectual one, on the part of a person to build a bridge between life and afterlife, between absence and a liminal presence. Now, with children having to write untimely wills, assured by the certainty of their perishment, these documents have been invested with the power of a moral compass to measure the immorality of our restive, violent times and spaces — be they Gaza, Kyiv or Kashmir.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in