It is a decidedly odd combination. Akin to the proverbial chalk and cheese, if you will. Yet, an old Bengali cookbook, Bipradas Mukhopadhyay’s Pak-Pranali, which dishes out recipes from 19th-century Bengal, insists that mutton and bitter gourd — you have read it right, dear reader — make for perfect companions on a dish.

The offspring of their dishy companionship, Karalar Dolma, would, in all probability, lead to a temporary ceasefire in the simmering culture war between vegans and carnivores in India. Both sides are likely to be bamboozled by this concoction. How on earth, meatloathers and eaters alike would wonder, can bitter gourd stew in the company of mutton? This sense of wonder, though, is the sign of a national amnesia. The fact that food can be truly secular, in keeping with the Republic’s pluralistic moorings, representing elements of seemingly conflicting genres, vegetables and meat in this instance, is something that foodies in New India may have forgotten. Karalar Dolma, then, ought not to be seen merely as a dish; it ought to be savoured as a mnemonic treat, one that reminds India of its fraying pluralist, representative ethos.

That, however, is not the only contribution of Karalar Dolma, or so insists the creator of ‘Golpo-Dadu’, an Instagram handle that ostensibly rescuedMr Mukhopadhyay, his singular book, and its recipes from oblivion. March, which ushers in Spring, it can be argued, is the month of maladies. This is because its colourful hues notwithstanding, basanta, which heralds winter’s retreat in the face of a fiery, approaching summer, is synonymous with many a seasonal ailment — small and big. From chickenpox and mumps in children to allergies, asthma, and gastroenteritis in adults, March brings home an array of ailments — including the occasional pandemic: Covid-19, which upended modern ideas of public health, treatment as well as ways of living and working, was, incidentally, declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization this very month five years ago. Not everyone would remember that over 100 years ago, another March had unleashed the horror of the Spanish flu on the world. Bitter gourd-mutton, Bipradas Mukhopadhyay’s Pak-Pranali claims, could serve as a robust defence against some of March’s afflictions, at least the minor ones.

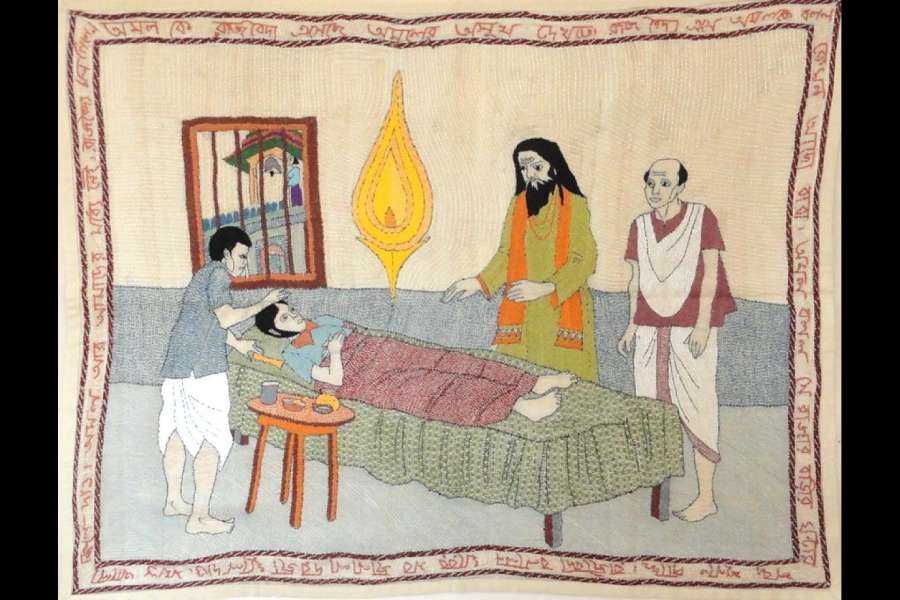

Not only mortals but the gods, too, seem to have taken note of the March Maladies. In fact, the Hindu pantheon has a specific goddess with the power to bring down the heat associated with fevers of this time and season. Sitala, the cool one, could not have climbed the strictly hierarchical divine order had it not been for her association with ailments that are the bearers of febrility: poxes, especially the dreaded smallpox, malaria and suchlike. Even though “Sitala Mangal” does not quite occupy a pride of place in the tradition of Bengal’s Mangal-Kavyas, poems of benediction/religious texts that were composed between the thirteenth and the eighteenth centuries in honour of indigenous deities, especially those that dominated social life in rural Bengal, an old abstract in The Journal of Asian Studies points out that an examination of the aetiology of diseases would suggest that the emergence of poxes in the form of epidemics in colonial Bengal’s countryside in the nineteenth century had led to a churn in Sitala’s fate, with the divine lady with her cool, healing touch emerging as a central figure in Bengal’s socio-religious consciousness. That she remains a potent force even in modern times was revealed during that pandemic-afflicted March. Deepsikha Dasgupta’s piece, titled New Diseases, Old Deities, unveils a telling scene, that of a mask, the only ‘antidote’ available before the discovery of Covid vaccination, being cast aside by a devotee while entering a Sitala temple. The gesture was not only suggestive of the pandemic’s inability to puncture the faith in Sitala’s powers of convalescence but was also indicative of an intriguing inference that was drawn by Dasgupta: in India, the coronavirus pandemic had witnessed a confounding coexistence between enhanced biomedical understanding of modern disease and a religious imagination that seemed to have been nourished, instead of being vanquished, by the democratisation of scientific information in the public realm.

Pestilences, rather than benign seasonal ailments, have had the power to spur the imagination, especially the literary imagination. Nights of Plague, Orhan Pamuk’s exposition of the bubonic plague and its orientalisation in literary works that preceded his, including Albert Camus’s celebrated The Plague, is but one example of the novel responding to the undercurrents — social, economic and psychological — of pandemics. Two of the finest literary explorations, albeit in different formats, of the human tragedy that is associated with such duress, are perhaps Rabindranath’s play, Dak Ghar, as well as Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s short story, “Pnuimacha”.

In comparison, minor maladies such as seasonal fevers and flu, the ones that bring suffering but do not necessarily snuff out lives, seem to have received scantier reflection from thinkers and writers. (“Leela Majumdar’s “Pilkhana”, wherein a child struck down by a contagious illness is taught about the values of companionship, fortitude and, ultimately, liberation by a spectral elephant trainer and his herd of lovable, ghostly pachyderms and Satyajit Ray’s “Sadanander Khude Jagat”, where Sadananda, frail, sickly, but with a fine sensibility, befriends ants, are exceptions that come to mind.)

But Spring illnesses, especially those that strike us in childhood, can be formative, even emancipatory, experiences. I remember my grandmother nursing me, a child emaciated by chickenpox, with stories of her — our? — ancestral home that now falls in another country. Since then, I have not been able to dissociate the duality and the elusiveness of the idea of home, of belonging, with a feverish longing that was, I now realise, literal and metaphorical. The realisation that the passage of time can seem infinite, because of its slowness, and, yet, unfold within the transient, blink-and-you-will-miss brevity of a single day, was also brought to me, decades before the March lockdown and our subsequent work-from-home existence, by a bout of flu during which, I remember, I used tofollow the unhurried movement of a sliver of light from one chequered squareof floor tile to another. Such revelatory experiences would undoubtedly becommon in a collective register of individual reminiscences of seasonal, childhood afflictions — if only there wereto be one.

Karalar Dolma, Bipradasbabu assures us, can keep the March Maladies at bay. But in doing so, it may rob us of an enlightenment, which, even though it dawns in the wake of an illness, lingers long after the malady’s banishment.