The Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 was a historic milestone for the advancement of women’s rights. Representatives from 189 governments came together to establish a global policy framework aimed at achieving gender equality that was outlined in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

In India, civil society organisations hosted a series of transformative grassroots consultations over two years (1993–1995). Supported by various women’s groups, the coordination unit facilitated this process to amplify the voices, agency, and leadership of such marginalised women as women living with disabilities, women living with HIV/AIDS, Dalit women, and single women. The Advisory Committee, which organised the consultations, went on to form the National Alliance of Women, which continues to raise the voices of Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, working-class, and other marginalised women.

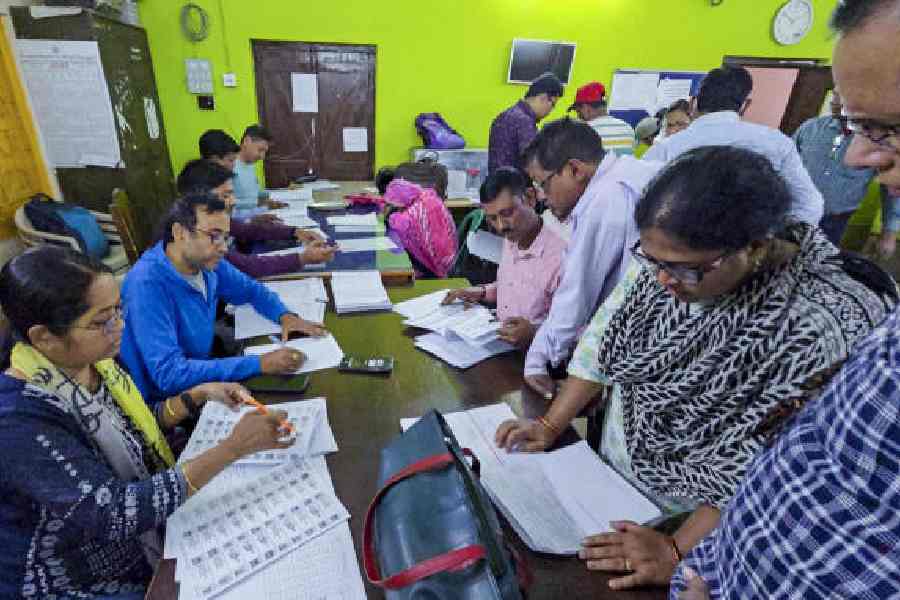

This year, the world will mark the 30th anniversary of the FWCW and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Civil society, under the auspices of UN Women, organised globally to inform the 69th session of the Commission on the Status of Women at the United Nations headquarters in New York in March. As part of this national and global process, the eastern region of India held one of the five in-person gatherings across the country. A diverse group of grassroots women from Bengal, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha came together in Calcutta for a dialogue. Among the concerns raised were the multiple intersectionalities that disempower marginalised women.

Among the many pressing issues highlighted was the criminalisation of child marriage. Young people facing discrimination often marry without parental consent. In such cases, should the parents or the community disapprove of the marriage? The ongoing discussion about raising the legal age of marriage to 21 makes this issue even more urgent. Instead of criminalising underage marriage, the focus should be on addressing its root causes.

Adivasi women spoke of their invisibility and pervasive poverty. The three ‘Ms’ — Mahua (alcohol addiction), Migration, and Maoism — affect their lives significantly. Climate change and deforestation exacerbate migration. The women who remain behind have to manage agricultural labour and household chores despite facing difficulties due to changing production systems and the absence of strategies to cope with new climate realities.

Adivasi and Dalit women and girls also have to deal with alienation. The establishment of separate hostels and shelters for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes leads to isolation and makes them more vulnerable to sexual abuse within institutional settings.

Lesbian and Trans women spoke of being forced into marriage before they understood their sexual preferences, leading to entrapment in an institution that does not address their needs.

In the broader discussion of violence against women, natal family violence was flagged as an overlooked issue. This form of violence takes several forms — physical, emotional, mental, psychological, and financial. Greater discretion in the hands of the police over the registering of cases leaves many women without access to justice. The growing number of single women and the increasing responsibilities women face for their families’ survival demand greater financial and management training for women.

These intersectional and inter-generational dialogues, occurring virtually and in person in preparation for Beijing +30, are crucial to addressing the evolving concerns of women. There must be more spaces for such dialogues to continue.