As a loyal Bengali, I am always in search of something new to brag about. Recognition, whether international or from near home, always helps keep the bragging juices flowing. UNESCO’s 2021 inscription of Durga Puja as an “intangible cultural heritage of humanity” provided a nice opportunity to beat the Bong gong, as did the recent recognition of Bengali as a ‘classical language’. And yet I keep looking for the next prize catch, as it were. What can be the next Bengali thing that can land some pretty legit laurels, preferably of the UNESCO inscription kind?

Suddenly, an idea occurs to me. Can mishti — Bengali sweets — fit the bill? Can UNESCO be persuaded to inscribe rosogolla and sandesh into the registers of human history?

On the face of it, why not? Food items and culinary practices specific to cultures get inscribed by the UNESCO every year. In 2024, inscriptions were accorded to Arabic coffee, cider drinking in the Asturias in Spain, Malaysian breakfast culture, Estonia’s traditional boiled potatoes with barley, Mulgi puder, the South Korean fermented sauce, Jang, Attiéké, a traditional dish made with cassava tubers in Côte d’Ivoire, bread-baking in traditional Tandir clay ovens in Azerbaijan, the Thai prawn soup known as Tomyum Kung, and particular varieties of artisanal cheese-making in Brazil, sake-brewing in Japan, and cassava bread-baking in several Central and South American cultures. That’s a total of eleven in a single year! Yes, you read that right.

With the winter on its way out and Bengal’s peerless date palm jaggery or nolen gur on its last hurrah this season, this seems to be an odd time to start singing the usual paeans to the region’s sweetmeat-making tradition. However, in anticipation of a possible pitch for inscription, why not start taking stock of the factors that make Bengal’s mishti a strong candidate? The antiquity of the tradition, the cross-pollination of different cultures that it has helped spawn, the diversity of artisanal creativity, and the impressive breadth of its appreciation across the board are, of course, important signposts to flag.

One of Alexander’s army officers, Nearchus, was dumbfounded to see Indians using a stick-like object (likely to be sugarcane) to make ‘honey’ without the aid of bees, so the anthropologist, Sidney Mintz, the author of Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1985), ascribed sugar’s origins to India. The landmark book, Bangalir Itihas: Adi Parba, by the historian, Niharranjan Ray, described one of ancient Bengal’s names, Gaur, as a derivative of gur — jaggery or molasses — because of the abundance of sugarcane plantations in the region. The Vaishnavite ‘Chaitanya’ texts of early medieval Bengal are full of references to a wide range of sweets made with milk, kheer, coconuts, and fruits, most notably dahi, laddus, payesh, and sandesh, which at this time were little more than solid lumps of sugar.

Medieval India’s Muslim rulers introduced the tradition of cooking flour, semolina, rice flour or gram flour with sugar, ghee, and milk — adding nuts and raisins brought from Central Asia — to make assorted halvas, which christened Muslim confectioners as halwais or haluikars. To this landscape, the Mughals added a range of goodies, including jalebi, imarti, gulab jamun, balushahi, firni, and rice pudding or shirbirinj, nearly all of which had Central Asian connections and all of which Bengal embraced and made its very own. And then, of course, came the Europeans, with the Portuguese in Bandel — apocryphally — helping overcome the longstanding Hindu taboo against curdling or ‘breaking’ milk (an offering for the gods) by making chhana and experimentally drowning it in sugar syrup to create the Big Bang moment, the birth of the rosogolla, and to simultaneously spawn the transformational efflorescence of the sandesh! This origin theory is hotly disputed by other claimants from West Bengal, Odisha, and Bangladesh, but isn’t that true of all metamorphic moments in human history?

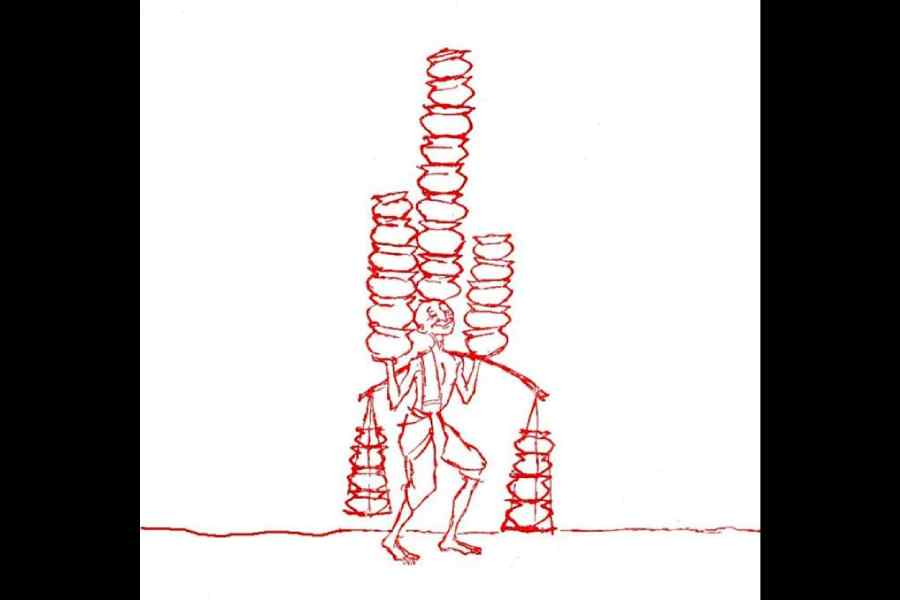

The regional diversity of artisanal craftsmanship in Bengal’s sweetmeat-making tradition is bewildering. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the patronage of Bengal’s zamindars helped the growth of distinctive sweets in many of Bengal’s mofussil towns. Only a few of them have GI tags now — like the Bengal rosogolla, the sitabhog and the mihidana of Burdwan, or the puffed rice moa of Joynagar in South 24 Parganas, with its date-palm jaggery-laced aroma — but many more are no less worthy candidates waiting their turns, like the delectable sarpuria and sarbhaja of Krishnanagar, or the ledikeni of Berhampore in Murshidabad district, a variant of gulab jamun believed to have been named in honour of the Vicerine, Lady Canning, visiting the town in the wake of the Revolt of 1857. The depths of this regional creativity are truly fathomless.

And, of course, Calcutta adds its own creative clout to this bounty, particularly in sandesh, which the food historian, Colleen Taylor Sen, describes as “the emblem of Bengaliness”. Starting from nineteenth-century experimentations in expanding the sandesh’s flavour horizon through the addition of mango, jackfruit, lime, and orange pulp and essences as well as nolen gur, the city’s artisans have gone on to try their hands at saffron, pistachios, rose water, vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, kiwi, and, lately, even rum, vodka, brandy or whisky. It’s little wonder, therefore, to find only Bengal’s sweets — from within India’s vast desert platter — described at length in weighty, authentic tomes like K.T. Achaya’s classic, A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food (1998), or the more recent global compendium, The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets (2015).

Isn’t it possible to compile some sort of a reliable ‘creative economy’ report on Bengali sweets, of the kind that was put together for the Durga Puja by the British Council and West Bengal Tourism in 2020-21 — one that assessed the value of economic activities around the Puja to be in excess of Rs 320 billion and formed a critically important component of the application dossier to UNESCO? The historian, Michael Krondl, who writes extensively on the world’s desserts, including India’s, estimated the ‘Bengali sweets economy’ to be worth around Rs 16 billion in 2003. Merely adjusting for inflation — even leaving aside the seemingly ceaseless expansion of the industry — will raise this figure to around Rs 50 billion today. Surely, a research team can pull off more accurate statistics?

To make a quick visit to the dark side, there are a couple of grimmer facts to grapple with. First, sugar makes people susceptible to diabetes, and West Bengal takes its place, along with Kerala and Tamil Nadu, among Indian states with the highest prevalence of Type 2 diabetes. Second, the milk of cows and buffaloes has one of the highest carbon footprints among the world’s foods. India produces an average of 230 million tonnes of milk annually, the most in the world, more than twice the amount produced in the United States of America and five times that in China. There can’t be any prizes for guessing why and in what form a huge part of this milk is consumed by Bengalis. So, grim as it sounds, there can be little debate on this particular aspect of Bengal’s footprint in today’s world.

But surely, Bengal also has the wherewithal — intellectual and otherwise — to deal with these two red flags. The food technology departments of its universities have done pioneering research to introduce sugar-free mishti to the Bengali palette. Can we find a low-emission version of eco-milk that, in combination with sugar substitutes, would mitigate the dangers of our sugar cravings, keep this unique industry thriving, and ease the furrowed brows of a UNESCO jury? I am ready to wager a couple of years of my life on this — or, well, a couple of weeks maybe?

Jayanta Sengupta is Director, Alipore Museum; jsengupt@gmail.com