Each summer, the mango returns. More than a fruit, it brings memory, hunger, and home. But its sweetness hides a long story — of land, caste, care, and power.

Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor, planted mango trees along roads for all beings. The historian, Romila Thapar, says that these trees were part of his State’s public care.

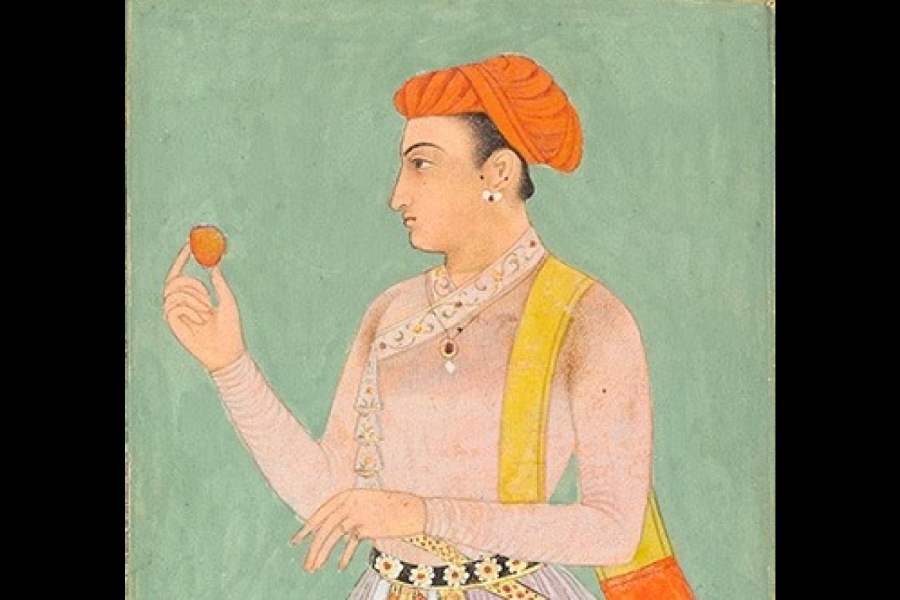

Later, Mughal rulers like Akbar offered tax breaks to farmers who planted orchards. The historian, Irfan Habib, has shown that mango trees were seen as infrastructure. They were not only food, but part of the rural economy.

In Bundelkhand and Chotanagpur, Adivasi and pastoral communities planted mangoes as part of village wealth. Verrier Elwin documented how tribal councils protected these trees. They were not private property; they belonged to the commons. For Dalit and landless communities, mango trees were lifelines. In eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, people still say that the mango is a poor person’s fruit, feeding families when nothing else does. Oral histories collected by Badri Narayan and Gail Omvedt tell us how mango pulp with roti kept people alive during lean summers. Dalit families who were excluded from grain storage or charity turned to trees for food.

The mango also appeared in seasonal rhythms. In Mithila, Maithili and Bhojpuri songs remember women, lovers, and migrants resting under mango shade. These trees witnessed daily life and local justice. Disputes were settled, songs sung, and meals shared beneath them.

This system changed under British rule. The 1793 Permanent Settlement turned land into private property. Commons were enclosed. Mango orchards were destroyed to measure taxable land.

Forests in Bengal and Bihar were logged for railway sleepers. The ecologist, Pallavi Das, notes how mango belts shrank under colonial timber demands. The colonial approach was to cut off food from ecology. Mangoes thus became symbols of decay instead of shared wealth.

After 1947, mango exports became a status symbol. Alphonsos were gifted to diplomats. But local trees disappeared. In Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, cash crops replaced mangoes. Orchards became land for real estate or borewells. In Maharashtra’s Marathwada, drought and farmer debt wiped out orchards. Agro-economists like R. Ramakumar have noted this shift. Trees that gave food for decades were replaced by crops that failed in a few years. At the same time, mango became a luxury. TV ads sold it as bottled nectar. City markets priced it high. The aam was no longer for the aam aadmi.

In Satyajit Ray’s, Pather Panchali, a child steals a mango out of hunger. The moment is small but sharp, revealing poverty, shame, and longing. Tamil films often use mangoes as metaphors for desire. In The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy writes of mangoes being thick with caste and memory while in Saadat Hasan Manto’s stories, mangoes appear in Partition camps as the last sweet taste of home.

India needs a mango policy. Not for trade, but for care. The mango tree is drought-resistant, long-living, and low-cost. It should be counted as public infrastructure, like roads or wells. Schools, railway stations, bus stops should preserve old mango trees. Gram panchayats should plant new ones, especially in Bundelkhand, Vidarbha, and the dry zones of Telangana. Agroecologists like Vandana Shiva have long argued for food sovereignty through local crops. The mango fits this vision. Heritage orchards must be marked as ecological commons. States can offer incentives to protect groves.

Upendra Baxi once wrote that welfare is the “grammar of care”. The mango tree lived by that grammar. It shaded without asking for caste. It fed without asking payment.

The mango can return as the people’s tree. Not as bottled pulp, but as public policy. Not as private orchard, but as a shared root.

Naina Bhargava is founder and editor of The Philosophy Project