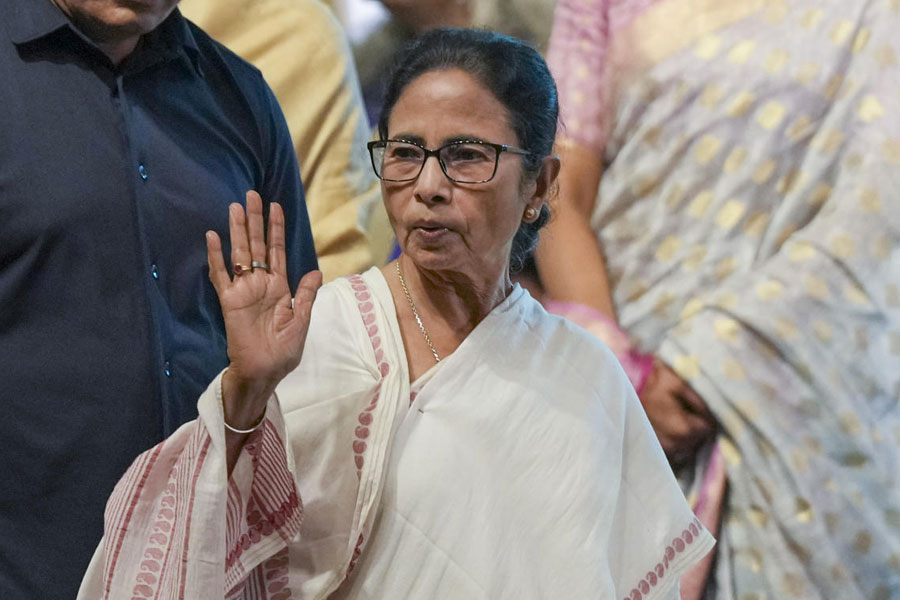

The Bengal chief minister’s recent outreach to the fraternity of doctors at various levels of seniority — her first engagement since a segment of young doctors led a spirited protest after the rape and murder of their colleague at the R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital last year — can only be described as placatory. During her interaction, Mamata Banerjee made a number of telling announcements. Her government, for instance, announced a pay hike for junior and senior residents. Ms Banerjee also permitted government doctors to engage in private practice within 30 kilometres of the hospital where they are posted, raising it from the current limit of 20 km, even though she did remind senior doctors to adhere to the mandatory eight-hour work shift in government hospitals. These interventions need to be looked in the larger context: and that context is political. It must be mentioned that Bengal had witnessed unprecedented public participation in the protests led by a section of the junior doctors after the horror at the R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital. Ms Banerjee cannot afford to alienate either this constituency or public sentiments a year before crucial assembly elections.

But Ms Banerjee’s largesse should not deflect attention from the many weaknesses that plague Bengal’s healthcare sector. Some members of the Junior Doctors’ Front have taken the opportunity to state that crucial demands that they had put forward remain unmet. Embedded corruption in healthcare, a large number of vacancies in government hospitals, the demand for a central patient referral system that would facilitate the streamlining of patient flow towards appropriate hospitals and specialists are issues that demand immediate intervention. These are not the only warts. The alleged existence of ‘lobbies’ within the medical system with disproportionate influence, poor doctor-patient ratios, especially in rural areas, paucities in healthcare infrastructure in Bengal’s hinterland, the resultant tendency of district and rural health institutions to refer patients to hospitals in Calcutta, leading to clogging — these structural impediments cannot be addressed with attempts to mollify health practitioners. National Family Health data have indicated that in Bengal, an estimated 69.6% of households depend on public healthcare facilities. Their improvement, and not populism, should be Ms Banerjee’s priority as health minister.