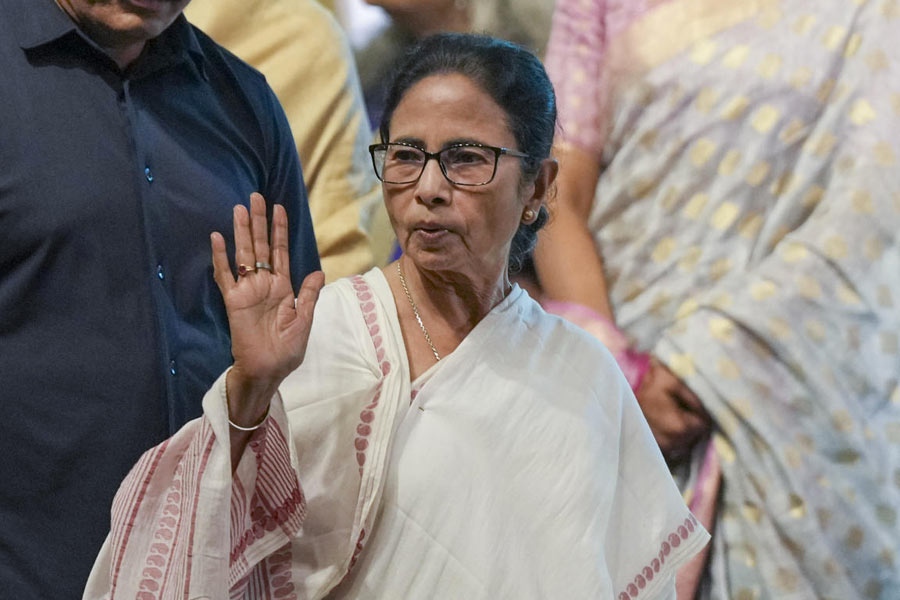

The view that the prime minister being the high priest at the consecration of the Ram mandir signifies the end of Indian plurality and secularism is naïve. Rahul Gandhi sought to visit the birthplace of a 15th-century Vaishnavite religious leader in Assam during his Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra, but was denied permission. A Jagannath temple, spread across 22 acres, is coming up in Digha: it is being touted as Mamata Banerjee’s answer to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s efforts to project her as ‘anti-Hindu’ and a ‘minority appeaser’. Arvind Kejriwal had once asked Narendra Modi to put the pictures of Lakshmi and Ganesh on Indian currency notes to revive the economy. Minority religious leaders often ask their followers to vote for ‘specific’ candidates, while Indian communists thrive on votes from religious minorities. If secularism has, indeed, failed in India, the answer perhaps lies in such phenomena.

The separation of the sacerdotal from the temporal and the confinement of religion to the private sphere never really took off in India. Competitive electoral politics and the subsequent rise of Hindutva marginalised the secular ideal. Even if we concede that secularism became a dominant principle after Independence, it remained highly contentious. A look at the Constituent Assembly debates will reveal the rejection of proposals to incorporate ‘secularism’ as part of the Preamble, something that took place only with the 42nd Amendment in 1976.

The failure of secularism as a policy has been attributed to it being ‘Western’ in provenance, with Jawaharlal Nehru and other Westernised leaders blamed for imposing a concept that was utterly alien to the Indian social and cultural milieu. While conversing with the famous French novelist and art theorist, André Malraux, in 1958, Nehru confessed how he faced an insurmountable challenge in his attempt to create “a secular state in a religious society”. Independent India’s leaders decided that the nation needed to be a secular State to hold its disparate communities together. The intention was noble, but it was bound to be plagued by contradictions. The piquancy of India’s situation lies in its secular Constitution having to contend with a State with expressive religious intent.

Decolonising narratives are now coming home to roost. It is being argued that religion was at the heart of the East India Company’s relationship with India, but the free exercise of religion, the policy the Company adopted in its early days, was challenged by evangelicals in the late-eighteenth century seeking to put an end to ‘barbaric’ Indian religious practices. The bottom line? England, from which we derived many of our laws and institutions, was not a ‘secular’ country when it ruled us.

Previously discredited communal ideologies are now being given a second life, leading to polarising and chauvinistic-nationalistic frenzies: Kashmir, Punjab, Nellie, Meerut, Ayodhya, Shah Bano, Mandal, Gujarat, Manipur are a few examples.

The noisy, rambunctious nature of religious practices now dominates the public sphere. The failure of the Indian State to distance religion from politics and to prevent the rise of a toxic culture that thrives on the memories — real or imagined — of millennial animosities account for the demise of secularism in India.