Completely by chance, three very different films I watched recently clicked into one another thematically. The first of these was Marshall, about an early rape trial fought by the lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become the first Black judge of the US Supreme Court; the second was The Brutalist, the much celebrated epic about a fictional, modernist architect, László Tóth, and his obsession with a grand project commissioned by a Pennsylvania millionaire; the third was the biopic about Bob Dylan's early career, A Complete Unknown.

In Marshall, the young Black attorney working for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People is sent to Connecticut to represent a Black chauffeur accused of raping his employer, a wealthy Caucasian woman. It is 1941 and racial prejudice is rife in the New England state; the local judge allows Marshall to be present in court but bars him from speaking; the actual arguments and cross-examinations must be executed by a White attorney, in this case, the reluctantly enlisted Jewish insurance attorney, Sam Friedman. As Marshall investigates the case and the trial unfolds, both he and Friedman are subjected to threats and violence, racial and anti-Semitic. As the movie proceeds, we realise this is as much a buddy movie as a film about a trial infected by racism.

In the much celebrated The Brutalist, a noted Jewish-Hungarian architect survives the Nazi death camps and arrives in the United States of America as a complete unknown. He is given grudging shelter by a parsimonious cousin in Philadelphia before he accidentally crosses paths with a millionaire who figures out how important Tóth used to be in the pre-War European design world. The millionaire takes Tóth under his wing and commissions to him a huge project — a community centre on a hill near his mansion. The relationship between patron and architect becomes a kind of microcosmic portrait of the dynamics between capitalism and art; Tóth's almost lunatic obsession with the on-again, off-again project becomes a metaphor for the way many artists render their work primarily to service their own ego.

In A Complete Unknown, a twenty-year-old Bob Dylan arrives in New York City, a novice singer who worships the legendary Woody Guthrie. Dylan meets Guthrie and Pete Seeger and the latter promotes the young musician's unmistakable talent. Dylan gains fame rapidly, first for his style of singing and, then, for the brilliance of his own songs. As his own fame begins to snowball, Dylan oscillates between his first girlfriend and the already famous, incandescently talented, and beautiful Joan Baez.

As a young student who carried his own Dylan-worship and Blues-obsession to the US and to New York City, it took me a while to understand the very obvious resentment I witnessed between ordinary Jews and African-Americans. A light bulb began to come on when I caught an angry mouthful from a fellow African-American student from the Bronx. I was startled at the anger the man radiated towards me, I who naively identified with Black music and the anti-racist cause. I may have loved Jimi Hendrix and been in awe of Martin Luther King but my fellow student saw in me all the racist Indian (South Asian) doctors who routinely mistreated Black people in the public hospitals in New York. As brown 'aliens', we desis were looked down upon by the Whites, yes, but we, in turn, had also lost no time in installing (or in the case of desi immigrants from Africa, re-igniting) our own naked disgust towards those we called 'kaaliyas'. Before the waves of desi migration hit the US in the late 1960s and the 1970s, it was, I understood, the Jewish community which chiefly consisted this middle layer in the racism sandwich, dealing with but keeping its distance from the 'goys' (non-Jewish Whites) with far stronger prejudice against the 'schwartzes' (the Blacks). In the meantime, sections of White society, such as the good ol' boys of the Ku Klux Klan (many of whose descendants now hold positions of great power in the current American regime), had no problems hating Blacks and Jews with equal ferocity.

In that outlier of a radical-liberal New England college, I acquired close friends who were African-American and Jewish and a roommate, Ethan, who was Jewish but not particularly a friend. When I arrived in America, my sympathies largely lay with Israel, steeped as I was in the history of the Holocaust and the post-World War II narratives that stemmed from the death camps and the formation of Israel as (I imagined) a democratic, liberal, secular, socialist outpost surrounded by a jungle of reactionary Arab despotisms. Ethan was the first indication that there might be something flawed in my understanding of what was going on in western Asia. Any argument I might put forward about the rights of Palestinians to their own State was met with anger and an unmoving assertion that these people needed to be “pushed into the sea”. 'Islam' wasn't something that was playing too widely in the America of the late 70s and the early 80s but the events of 1982, with Menachem Begin's invasion of Lebanon, had already begun to pry the bricks out of Israel's liberal-democratic facade: if young Ethan wanted to shovel an entire population into the Mediterranean, my 60-something landlord in New York, Mr Chill, informed me that he was taking a holiday and going to Israel “to kill some Arabs”. It's only later I realised that for the ignorant, ageing yokel, I too might have been an Arab or was only vaguely different from one.

There are, of course, great examples of Blacks and Jews working together to dismantle racial segregation and being killed for their efforts. Dylan's own songs, so many stemming from the Blues, so many championing anti-racist figures and causes, are yet another example of people overcoming the stupidities and the viciousness of their communities. But now, as you see a Black lawyer and a Jewish lawyer getting pally in 1940s America, you can't help suspecting some forced joinery in the scriptwriting. While Marshall may have been a great man, you also see the corruption of a Clarence Thomas, an associate justice of the US Supreme Court, awaiting people in the future. Today, when you see a young Dylan singing “Masters of War” in a Greenwich Village basement, you realise with a small shock that the Netanyahus with their Pegasus worms and Israeli weapons systems are as implicated by the song as any Putin or anybody in the US military-industrial complex. Now, when you see the tortured nightmares of a death-camp survivor in a film like The Brutalist, when you see the faint light at the end of the tunnel (an image used by so many films about the Holocaust), you stop yourself from digesting that sign of hope; when you see the architect's niece and son-in-law saying they're emigrating to Israel, you also see their grandchildren completing a macabre circle, committing remote-control genocide by drone and missile.

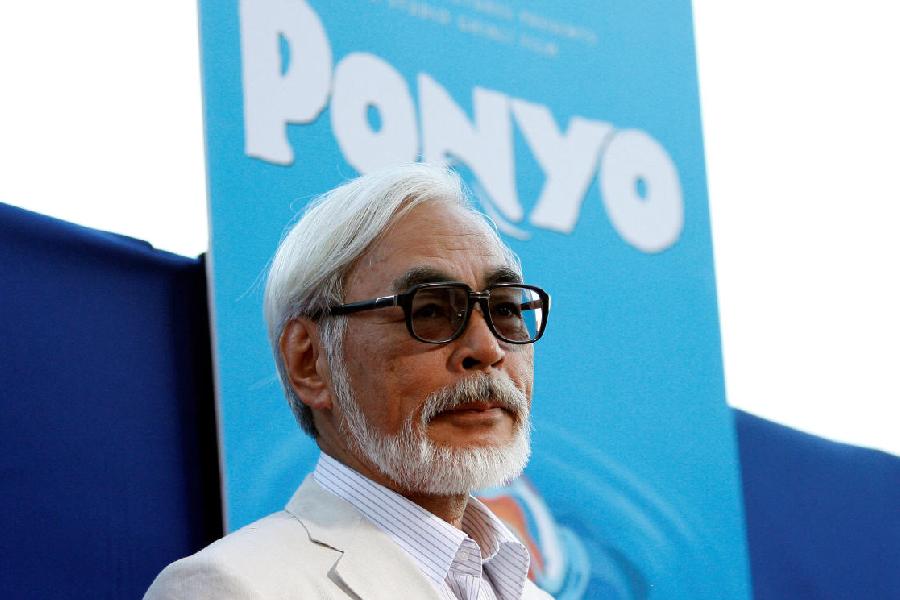

![Stills from the films, 'The Brutalist' [left] and 'A Complete Unknown'](https://assets.telegraphindia.com/telegraph/2025/Mar/1742262585_new-project-2025-03-18t070756-217.jpg)