India has walked out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India may have concerns about agricultural products from Australia and New Zealand, but New Delhi’s real worry lies with China.

The Indian social media has been abuzz with calls for boycotting Chinese goods, which have flooded Indian markets. This does not augur well for the country. But a call for boycotting Chinese goods is unwarranted. It is indeed difficult to find Indian products in numerous consumer durable segments. Worse, many of the products sold by reputed Indian companies are made in China.

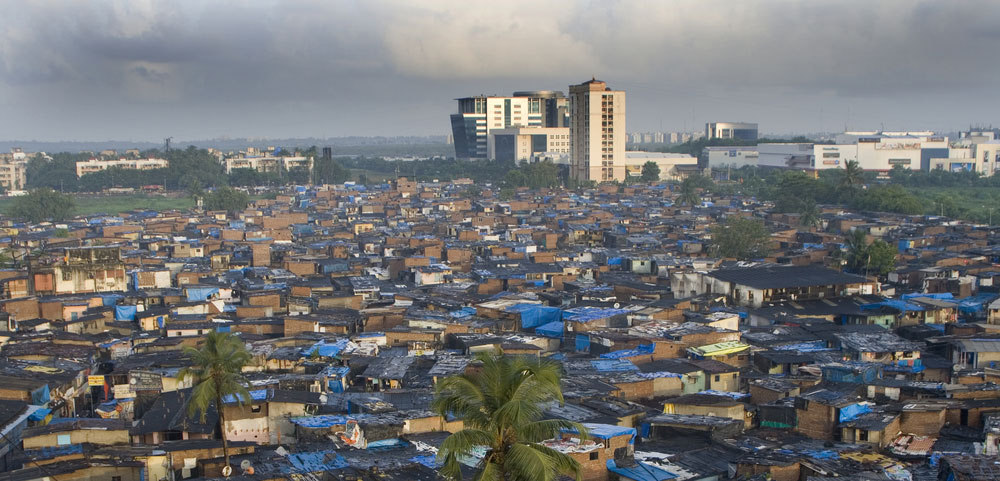

India has been basking in the glory of its ‘success’ in the services sector. Now that our services-led growth model is under stress, we must reflect on what has gone wrong. A study by an economist from Bangladesh has argued that South Asian countries, with the exception of Bangladesh, are experiencing premature de-industrialisation.

After reaching a certain stage of development, nations shed the share of the manufacturing sector in the gross domestic product but India has been doing so prematurely.

In the early 1990s, India adopted what is often called the ‘LPG’ — liberalization, privatization and globalization — policy. However, we ignored the fact that this strategy included elements with differential impacts. It is possible that the level of protection that India accorded to its industries at the time was not enough. Admittedly, it was not easy to attribute the constraints in economic growth to different types of policy domains. India did not face any significant adverse effect from import liberalization not only in the early 1990s but also in the aftermath of the substantial tariff reduction that had to be implemented with the establishment of the World Trade Organization.

However, things changed drastically after China became a member of the WTO. For developed countries, Germany being an exception, it has been quite common to see the share of the manufacturing sector falling with the arrival of China. In India’s case, it was not a decline in absolute size but a fall in the share of the manufacturing sector. While India expected big gains in such sectors as textiles, clothing and footwear, especially after the dismantling of the multi-fibre arrangement, in reality, it found it difficult to even hold on to its domestic market. Even the biggest apologist of free market economics, Paul Samuelson, expressed his apprehension in an article in 1994 that it might not be sustainable. But India did not think that it was necessary to have an informed debate on trade policy and continued with the reduction of import tariffs much beyond what was mandated by the WTO commitments. New Delhi did not think that there could be a case for optimum protection or an optimum structure for protection. This despite the fact that we had a clear example of industrial development with protection. Apart from pharmaceuticals, the automobile sector is the only industry that has shown some success in India — under substantial protection.

The automobile sector is the most protected industry in India today. Consumers do not complain that cars made in India are of poor quality or are expensive. Consumers, however, have serious concerns about Indian products being hardly available in some sectors. This forces them to depend on Chinese products, the quality of which is poor. The Indian automobile industry is offering quality products with competitive prices even in the absence of foreign competition as domestic competition is strong enough. This is one lesson that we have been ignoring.

To be fair to China, it has hardly put pressure on India to reduce import duties. The United States of America, on the other hand, keeps asking India to open its markets, while it raises tariff walls for its producers. In the past, it has been quite liberal in imposing anti-dumping measures on imports coming into the US. Ironically, this has benefited China. The solar dispute at the WTO, in which the US complained against India, is an example. India attempted to convince the US that the complaint would help China but the US was reportedly adamant.

India’s trade liberalization experience in the 1990s was vis-à-vis developed countries that brought some benefits. India maintained sufficient levels of protection too. Then, there entered the dragon in the room. In between 1995 and 2018, India initiated as many as 919 anti-dumping investigations of which 515 were against RCEP countries and 223 against China. This is also an indication of how ill-prepared India was when it came to signing the RCEP.

However, walking out of the RCEP cannot be an end in itself. India needs to engage in serious soul-searching to find an answer to serious lapses. For instance, why is it that India is not competitive enough? Finally, how can we enhance domestic competition in recognition of the fact that trade policy can play an important role in reviving the domestic manufacturing sector?