“...[R]evolutions are the only political events which confront us directly and inevitably with the problem of beginning.” — Hannah Arendt

Shaheen Bagh has captured the imagination of all those who are interested in democracy. No matter what the outcome of Shaheen Bagh and other anti-CAA protests across the nation will be, their place in India’s political history is already sealed.

The philosopher, Akeel Bilgrami, even goes on to argue that “no leader” in the history of 20th-century India — M.K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, B.R. Ambedkar or Maulana Azad — had “managed to do” what ordinary Muslims, especially women, have done: marrying popular pluralist religious practices with “the codes, rights and provisions of the law and of the Constitution”.

Yet, the extraordinary poetry that is being written by the largely ‘spontaneous’ and ‘leaderless’ anti-CAA protests has to confront, at some point, the mundane prose of leadership and organization. If this task is not undertaken, the efflorescence of democracy that the 70-year-old Republic is witnessing will remain stillborn.

The responsibility for the enormous task cannot be placed only on the protagonists of the story so far — Muslims or Muslim women. Any fundamental deepening or reinvention of democracy requires a substantive participation of society as a whole. That is why to expect Muslims only to bear the burden of protecting Indian democracy is the worst free rider problem of a political kind.

After all, the protests cannot, and should not, be restricted to be merely about the CAA-NRC, but have to be about extending Indian democracy in new directions at a time when it is facing its greatest crisis. Recent events suggest that it will face further shocks under the brazen onslaught of religious majoritarianism; the latest terrifying violence in Delhi is the inevitable outcome of open incitement to vigilantism by ruling party leaders and a completely mute police force.

In 2019, protests for democracy erupted across the world in various countries like Ethiopia, Egypt, Chile, Bolivia, Lebanon, Iraq, Spain, Hong Kong and so on. This is not unique as democratic dissent has been growing over the years as some recent global examples like the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement and Black Lives Matter show us. Until CAA-NRC, it was really anomalous that there were no large-scale movements against the systematic targeting of Muslims by the present regime in India, which culminated in the abrogation of Article 370.

What is crucial is, as the scholar, Erica Chenoweth, argues based on empirical data, that presently, nonviolent resistance is the most important mode of challenge to governments, representing “a pronounced shift in the global landscape of dissident activity.” From the 1940s onwards, nonviolent resistance began to gain strength, and achieved the highest success rate of 70 per cent around 2000. Shaheen Bagh is thus a classic demonstration of the global trend towards eschewing violence in the struggle to establish or reclaim democracy.

But why we cannot remain at the level of romanticizing Shaheen Bagh as a spontaneous movement only (“without the eminence of great leaders to shape it,” as Bilgrami calls it) is because the power of the State that it is contending with is simply of an extraordinary magnitude. This power will go to any extent to decimate a nonviolent movement. As Chenoweth shows, the success rate of nonviolent resistance has dropped to 30 per cent recently; one of the main reasons for this is that authoritarian leaders have developed “sophisticated techniques” to counter nonviolent resisters. What better illustration of such techniques than the one targeting, through fake news, the women of Shaheen Bagh as mercenaries on hire?

While Bilgrami is obviously referring to mainstream political parties when he hopes that “leaders don’t enter and ruin the political possibilities of resistance” at Shaheen Bagh, it would be Panglossian to believe that they can lead to substantive political changes without some form of new, or renewed, leadership to fuse together multiple sites of struggle. This was exemplified by the Occupy Wall Street protests, which were praised by commentators for their horizontal organization and the inclusion of a wide range of views without a central leadership or definitive demands. Nevertheless, the movement, while playing a stellar role in raising awareness of economic inequalities, also dissipated (with very little actual gains) once it confronted the massive force of the State, which controls the levers of legal violence.

Scholarship on protests shows that the critical factors in nonviolent movements succeeding even against violence by the State are organizational ability and links to broader democratic campaigns. Hence, the need for a stronger leadership and the larger civil society participating in the CAA-NRC protests seems vital. Here we see a sliver of hope through the Sikh community’s amazing support to Shaheen Bagh, the protests’ multireligious character in at least a few states, and the new inter-communal spaces being forged, like a Christian church opening its doors for Muslim prayers, or a mosque hosting a Hindu wedding in Kerala.

As the philosopher, Hannah Arendt, argued, all revolutions are about ordinary people creating new public spaces of freedom, like the French Revolution revolutionary clubs, the Paris Commune of 1871, the Russian Soviets of 1905 and 1917, and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. What is forgotten, despite the surge of global protests, is that the power of the State cannot be contended without the protests acquiring a pan-class character. As the scholars, Dahlum, Knutsen and Wig show, based on over 100 years of data from around 150 countries, industrial workers are the vital agents of democratization, even more crucial than urban middle classes.

Yet, this is where Indian democracy is facing a severe crisis; despite the highest unemployment rates in 45 years and extreme agrarian distress, the voices of the most exploited of economic classes — workers and farmers — are being scattered in the absence of a unifying leadership. The hollowing out of the mainstream parties that represented them, the deradicalization of the communist movement, and declining trade unionism are all parts of the story that has led to the right-wing appropriation of the most pressing issues of livelihood to the cause of the promised utopia of religious nationalism. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the National Register of Citizens cannot be seen in isolation from this. Therefore, the large protests at Malerkotla, Punjab, where farmers, workers and students came together, and the Dalit-Bahujan participation in CAA-NRC protests in Maharashtra offer one template for the future.

The most iconic movements for political freedoms and civil liberties can, without a broader social base or clarity of purpose, wither away and even turn thoroughly regressive — like the one in Egypt after the Arab Spring — or be repressed by the State — the political party that rose out of the iconic Gezi Park protests (which were initially only about environmental issues) in Turkey failed.

Shaheen Bagh and other protests across the nation can cause tectonic democratic effects, especially electorally, only if solidarity with it is broader. The Muslim vote does not matter to the ruling party anyway. This requires openness to the idea of leadership and new political formations even when being terribly aware that many people’s revolutions of the past have been sacrificed at the altar of dictatorial political power. Needless to say, any new political formation that should coalesce in the present cannot appropriate the agency of the women of Shaheen Bagh, or ordinary Muslims (like in the past), but has to be in a creative dialogue with them.

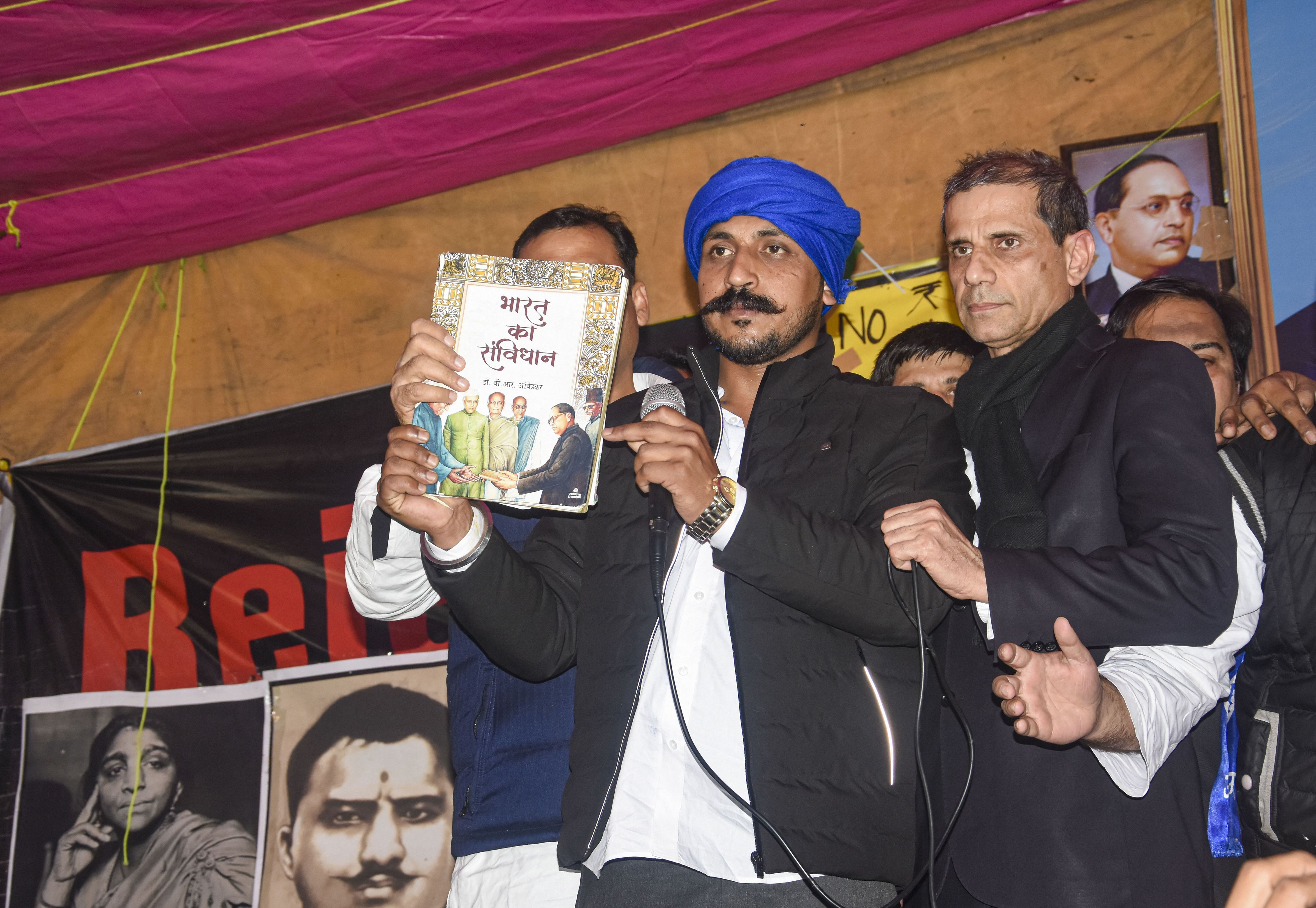

Chandrashekhar Azad, the Dalit leader, reading the Preamble to the Constitution at the Jama Masjid will be one of the emblematic images of the CAA-NRC protests. A Dalit-Muslim solidarity gives Indian democracy new hope. But it is also crucial at a time when the right-wing authored narrative of a perpetual Hindu-Muslim war is capturing people’s imagination to realize that there are no monolithic ‘Hindus’ or ‘Muslims’. Both these communities are marked by layers of severe internal hierarchies, not only of gender but also of caste and class. The logical culmination of the CAA-NRC protests should be a wholescale challenge to these hierarchies through solidarities forged across religions. For that, the luminous poetry of protests might have to be open to the ordinary prose of organization.