I am far from being the only one who has had problems with the shipping containers of post-modern theory that got dumped on our shores between the 1950s and the 1980s. A lot of it was useful no doubt, exciting even, opening up as it did new ways of thinking and looking at the world. From Barthes we learnt to interrogate language and signs in a way never done before; from Lacan we learnt to complicate an already problematic (for us, South Asians, among many others) Freud; from Derrida we understood that we must always take apart hitherto blindly-accepted philosophical ideas, to deconstruct them and see if they could be put back together in the same shape and function; from Foucault we learnt to look at the circuitry of power as being partly controlled by the faulty, erratic switches of knowledge.

One of the most interesting people from this unruly stable of Francocrat, thinker-thoroughbreds was Jean Baudrillard. Whereas it was easy to become irritated by the Occidocentric blinders of so many of his biradari, Baudrillard’s ideas of Simulation and Simulacra, his take on the effects of mass media, his contention that history had ended (by which he meant the disintegration of a way that a lot of the world used to look at the past) and why this was not such a great thing (as proclaimed by people like Francis Fukuyama) all seemed to speak directly to the lived experience of us, desis, as we traversed the rocky terrain of the late 20th and the early 21st centuries.

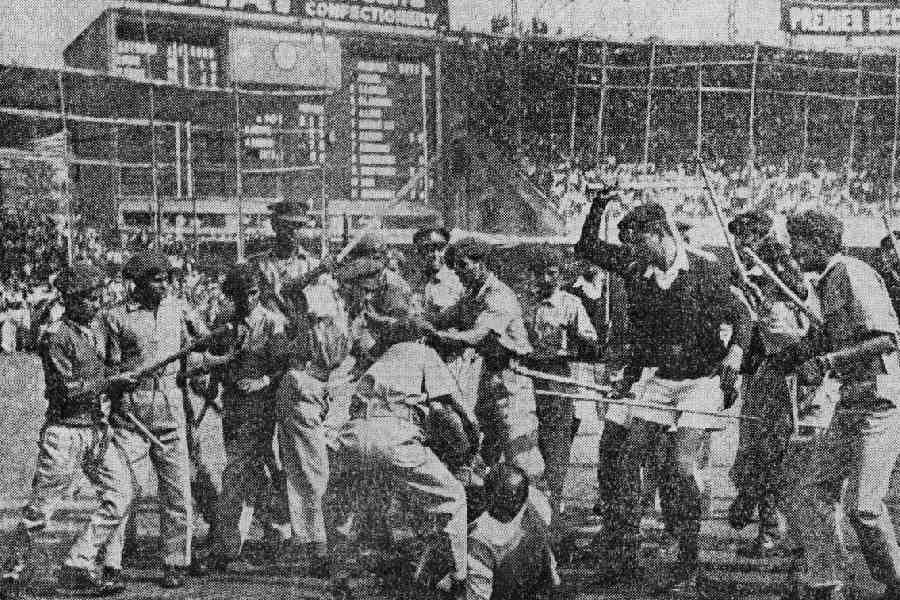

Perhaps it is useful to look at the disaster of Lionel Messi’s visit to Calcutta last Saturday by keeping some of the Baudrillardian notions within touching distance. But first, a little non-Baudrillardian history — the Messi Fiasco (as it may one day be called) is hardly the first time crowds and sporting events have combusted in our city. In fact, as Calcuttans, we wear the memories of the various flare-ups at sporting venues like soldiers wear campaign badges. There might have been other such incidents earlier, but the first one, the ur-riot so to speak, was, of course, at the Eden Gardens on New Year’s day 1967, during a Test match against the West Indies (picture). The organisers had oversold the tickets (reportedly 80,000 for around 59,000 places). Unsurprisingly, the ticket-holders wanted to come in and occupy seats, including the temporary bamboo stands, except that there were no seats to be had. Riots, arson and mayhem ensued as another sporting ‘GOAT’, Gary Sobers, and his team managed to escape from the stadium. The rioting spread to Esplanade and buses and trams were burnt. The match was almost called off. Sobers’s former captain and mentor, Frank Worrell, also happened to be accompanying the team and he had to convince the Great Gary to resume play after a day’s break (the rest day taken early) and beat India by an innings.

Next in the sequence would come the melee that took place when Pelé visited Calcutta with the Cosmos team in 1977. The trouble started at Dum Dum airport itself. There might have been other smaller upheavals but the next moment of note in this sorry series is March 13, 1996, when there was no problem of seating at Eden Gardens. A crowd of 110,000 people watched India implode against a relentless Sri Lanka in the semi-finals of the World Cup. As India teetered on the verge of defeat, the local crowd displayed the sporting spirit for which our city is so famous — they lit fires in the stands and threw bottles at the blameless Sri Lankan outfielders. Clive Lloyd, who had retired by then as the greatest West Indies captain, was the match referee. Lloyd had been a rookie member of Sobers’s Eden Gardens team in 1966-67. Twenty-nine years later, he had no hesitation in stopping play and awarding the match to Sri Lanka. If you imagined that this humiliation would have taught the Calcutta spectator a lesson, you could not be more wrong – three years later, this whole scenario repeated itself when Shoaib Akhtar and Sachin Tendulkar collided, leading to Tendulkar being run out. The crowd erupted at the Third Umpire’s decision and continued to be volatile when Sourav Ganguly got out a bit later, almost ensuring a Pakistan victory. The crowd was ejected and Pakistan won in an almost empty stadium.

A connoisseur of Calcutta’s sporting riots could point out that while the modes of expressing anger might be similar, the triggers for the incidents described above were slightly different. Some other argumentative Calcuttans would counter by pointing at the similarities across nearly six decades: while the 1996 and 1999 flare-ups had to do with India losing, the first Eden riot and the two football-related outbursts were directly related to administrative incompetence, corruption and to sporting officials and police hogging the proximity to the great sporting icons, not allowing worshipping fans even a clear look at their heroes. Whichever way you slice it, if you do the generational arithmetic, some of the young men running amok in 1967 would now be the grand or possibly even great-grand fathers of the people who smashed up Salt Lake stadium on Saturday.

What is it about Calcutta and its (largely male) spectators that bring about these incidents? After escaping Calcutta, Messi visited jam-packed stadiums in Hyderabad and Mumbai with no trace of any violence in either city.

While it set a precedent and carved itself into the public memory, Eden on New Year’s Day 1967 could be seen as an outlier. Perhaps the only continuity to be found, though an important one, is that people in this city and state carry and pass on generational trauma centred on deprivation and scarcity. This argument struggles against the fact that all over the world violence has erupted in and around football stadiums when there has been a botch-up with tickets for big matches. And, yet, there still seems to be something peculiar to our city vis-à-vis such moments. Here, Lacanian psychology is of little help, while Derrida’s jousting with language also fails us. Barthes and Foucault are somewhat relevant when you look at the significations of sport, specifically cricket and football, and the power relationships among the (often nepotistic, corrupt, media-avaricious) administrative bodies, the police, the politicians, media people and mega-star players.

However, when all is said and done, Baudrillard still provides the most useful modes of approaching this. Certainly, after the spread of TV and, now, the internet, it seems that the ‘ordinary punter’ comes to the stadium already carrying a simulacra of victory; that the quality of the real match, or quaint notions of being ‘sporting’, has no value — the punter is there for a win and if, for some strange reason, reality doesn’t deliver what is already programmed by the media, then all hell breaks loose, first in his mind and then on the actual stand or ground. In the instance of Pelé but especially that of Messi in Calcutta, maybe the crowds were demanding not just to be let into the ground, or to see and touch the idol, but to be allowed into history itself, to temporarily escape from the feeling of not just insignificance but actually not being real, of feeling two-dimensional; maybe they were demanding to burst into a reality that is recognised by the world, a hyper-reality if you will, of becoming 3D from 2D; and from there into a palpable hologram of themselves, moving from a kind of non-existence to a simulacra of immortality.