The Calcutta General Post Office (GPO) standing at the intersection of the Koilaghat Street and Netaji Subhas Road (formerly Clive Row) is one of the most iconic and enduring monuments of Calcutta. Designed by Walter B Grenville, the building with its distinct white dome was completed in 1868.

The General Post Office

Every day, hundreds of people walk up and down the staircases of the GPO. They are always in a rush and hardly ever stop to look at the steps on which they trod. If they are on the eastern staircase and stop to look carefully on the steps, they will observe something interesting. Barely visible at first glance, line of brass plates will be seen on the stairs. One would hardly realise these lines represent the remnants of a major chapter of the city’s history. These lines are all that remains of the first Fort William built by the East India Company in Calcutta.

Job Charnock may have been the most famous of the early Englishmen to come to this part of the country, but contemporary accounts hardly speak highly of him. To be fair, by 1690, when Charnock made his momentous landing at Sutanutee (somewhere between present day Nimtolla burning ground and Ahiritola ghats), he was already in his late years and probably didn’t have much enthusiasm left for affairs of the trade.

Certainly when Sir John Goldsborough arrived in the city on August 12, 1693, he found Charnock departed and things in complete disarray. Goldsborough immediately banished Charnock’s incompetent successor Francis Ellis to Fort St George (present-day Chennai) and appointed Charles Eyre, Charnock’s son-in-law as the new head of Company's affairs in Bengal.

Brass lines of Old Fort William at the General Post Office Wikimedia Commons

Goldsborough was appalled at the haphazard way of building construction and selected a suitable piece of land, which was surrounded by mud walls on all sides and a brick house was built here, as the new Government House from where Eyre was to function. This building was the genesis of the future fort. Records of the time seem to suggest that this strip of land was located to the north of present-day Custom House on Strand Road.

Charles Eyre started work on the fort in 1696. He was also the man who in 1698 signed the lease of agreement with the Sabarno Roy Chowdhury zamindar family, awarding the rights of the three villages of Sutanutee, Gobindapur and Kalikata to the Company.

While his father-in-law received the most plaudits from future generations of his countrymen, it was under Eyre’s stewardship that the Company consolidated its presence in their new citadel in eastern India. In 1700, Bengal became an independent presidency, answerable directly to the Company’s board in London. The fort was named after King William III in 1700. Construction completed two years later. Although technically a fort, the original Fort William was not designed as a military bastion. In those early years, the Company was still in the position of a humble trader and had not become the all powerful ruler of the lands. It was more a merchant settlement than an impregnable war base.

The GPO, the Customs House, the East India railway office building, and some other adjacent Government buildings of today largely represent the contours of the first Fort William. Fairlie Place, Netaji Subhas Road, Strand Road and Koilaghat Street represent its north/east/west/south boundaries respectively.

It needs to be remembered that today’s Strand Road was back then in the depths of the Hooghly. The river extended up to the eastern part of today’s Strand Road and its waves lashed the walls of the fort. In the early years, construction happened in phases primarily dependant on availability of funds. Eyre’s successor, John Beard (Jr.) constructed the north-east bastion (Eastern Railway offices on Fairlie Place today) in 1702 and a new factory/Government House in 1706. In 1709, the magnificent St Anne’s Church was consecrated as a place of worship of the fort’s residents. It stood outside the walls of the fort compound.

Lack of sufficient funds meant the church was never well maintained and in 1722, major restoration work was required. Only two years later, a bolt of lightning badly damaged the wooden structure. The spire of the church is said to have crashed during the dangerous cyclone that hit the city on the night of October 10, 1737. But the death blow was to come some 20 years later. On June 16, 1756. Bengal’s new Nawab, Siraj-ud-daulah arrived with his huge army on the outskirts of the city. Against his orders, the company’s governor, William Drake, had ordered external work on the walls of the fort.

Siraj-ud-daulah

The enraged nawab decided to teach the Europeans a lesson. Not built as a military stronghold, Fort William was ill equipped to take on the nawab’s forces. Governor Drake along with top officials cowardly escaped on ships before the main attack fell. Defence of the fort was left to John Zephaniah Holwell, a company official who had 500-odd soldiers of whom more than half were amateurs.

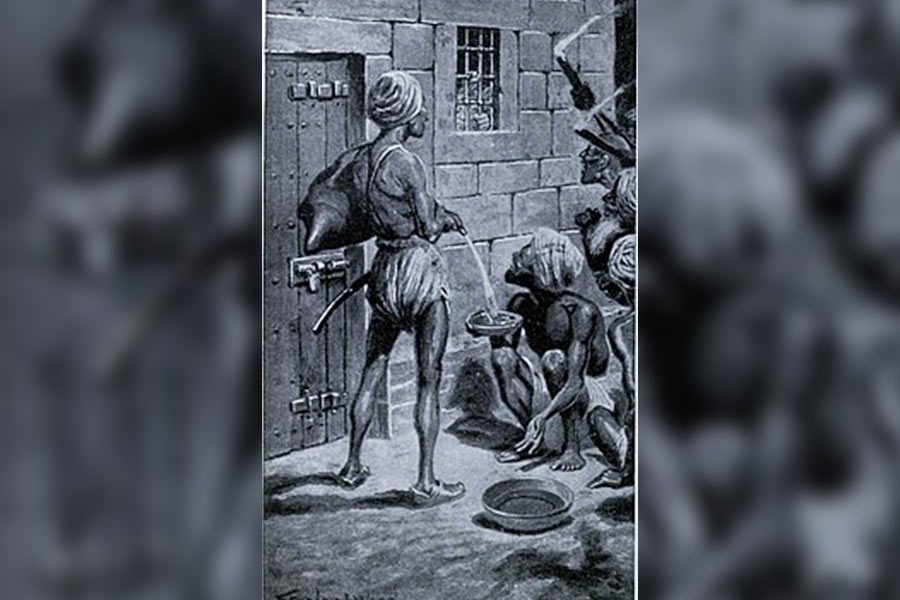

The battle if it can be called that was short-lived. Siraj-ud-daulah conquered the city, his forces ransacking the fort and leaving St Anne’s Church in absolute ruins. The nawab renamed the city, Alinagar, after his grandfather, Alivardi Khan. Holwell and the remaining survivors, a mix of English, Anglo-Indians and some Armenians and few Portuguese, were huddled together into a small 14 feet x 18 feet room. By Holwell’s account, 146 went into the room on a hot sweltering Calcutta summer night and by morning, only 23 survived, giving Calcutta its infamous Black Hole incident. Subsequent historians though disagreed with Holwell’s figure which they considered substantially exaggerated.

Illustration of Black Hole incident of June 20, 1756

The fort remained under Siraj-ud-daulah till January of next year when Robert Clive and Admiral Watson arrived from Madras and won it back.

In memory of the victims, a 15-foot obelisk was put up by the Company which came to be known as the Holwell Monument. The monument fell into disrepair and vanished sometime probably in the 1870s. After becoming viceroy, Lord Curzon ordered the commissioning of a new monument to mark the “massacre” which came up around 1901 (H.E. Buster – Echoes of Old Calcutta).

In the late-1930s, a massive movement erupted, led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, for removal of this monument. Eventually, in July 1940, the colonial administration was forced to remove the monument which was shifted to the campus of St John’s Church, where it resides to this day.

The precise location of the room is estimated to be in an alley way between the GPO and the building to its north, in the north-west corner of Dalhousie Square. Clive correctly surmised that the Fort was poorly defended and chose to construct a new well-fortified one.

The village of Gobindapur was selected as the site for the new fort. The old fort was demolished to build new government buildings. In 1776, the remnant of the St Anne’s Church was handed over to Thomas Lyon who built residential quarters for the Company’s writers there, later day named as Lyon’s Range.

Black Hole Memorial in Kolkata

Over time, the old Fort William gradually vanished from the conscious mind space of the city. All that remains today are the obscure brass lines from where we had started this piece.