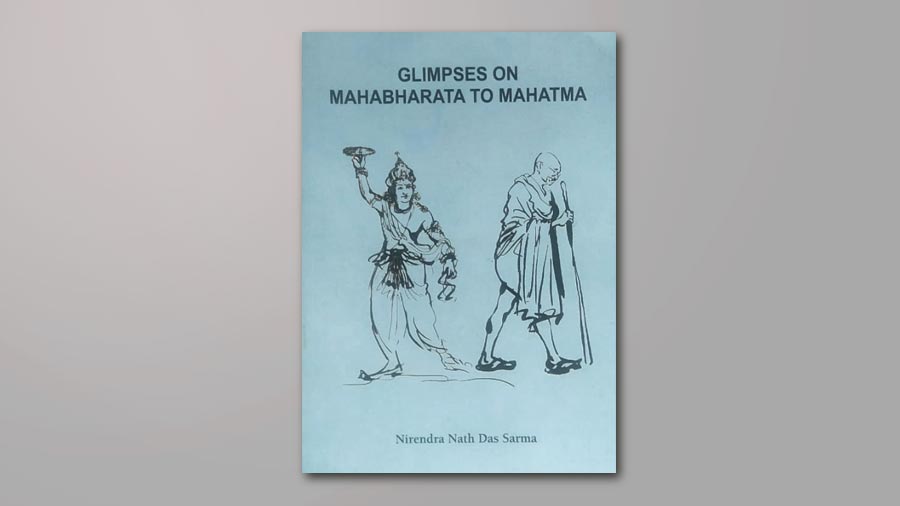

Nirendra Nath Das Sarma was a hundred years old when he started researching his book, Glimpses on Mahabharata to Mahatma. Although the phrase is frequently used as hyperbole, in this case it is simply a fact.

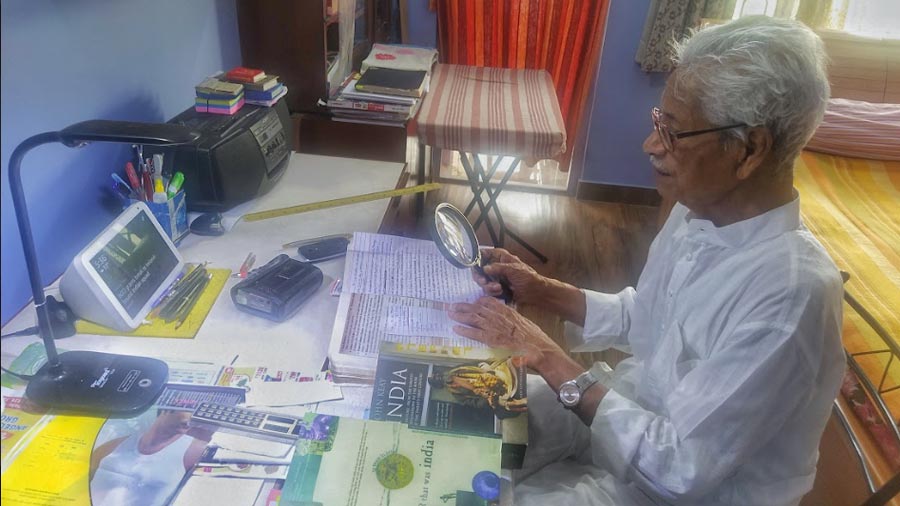

When we visit Das Sarma in his Golf Gardens residence, he’s seated at his desk, poring over history books with a magnifying glass and making incredibly neat notes in his writing pad. One would assume he has more than a passing interest in history; after all his own book traces mythological and historical events which begin with Brahma creating the world. But he’s not of the opinion that his interest in history is particularly absorbing. Now that it’s been more than four decades since he retired, he finds that chronicling the past is a respectable way to spend his days.

‘Glimpses on Mahabharata to Mahatma’ by Nirendra Nath Das Sarma was published in April 2022

We ask him to revisit the past with us. For a man whose lifetime has spanned one world war, two pandemics and Partition, what was life like a hundred years ago?

He smiles. “Simple.”

Snoopy the beagle won’t let him go back to his books until she’s been given a treat

Born on September 12, 1919 in the Faridpur district of undivided Bengal

Nirendra Nath Das Sarma was born on September 12, 1919 in the Faridpur district of undivided Bengal and later moved to Dinajpur where his father was in service to the zamindar – a descendant of Raja Ganesha who reigned during the medieval Sultanate of Bengal. Das Sarma was the fifth amongst nine siblings. One of his abiding childhood memories is coming home to find that his eight-year-old younger brother had drowned. Apart from that, his boyhood was not bleak, even though it was spent in a bamboo hut with a straw roof. Physical activity played a significant part, with boys competing in push-ups, wrestling and balancing on parallel bars. He remembers that through the years, various underprivileged children would be given shelter in the house and encouraged to study and grow up as one of his own brothers.

Lower division clerk at a princely salary of Rs 35

Das Sarma had aspirations of going to college, but unwittingly landed a job as a lower division clerk in the collector’s office. He thought it would be more responsible to take that up at a princely salary of Rs 35, with Rs 10 as a fixed travel allowance. After all, Rs 2 was enough to provide his family with two week’s worth of rice. “I saved Rs 3 a month because I had no addictions,” he says.

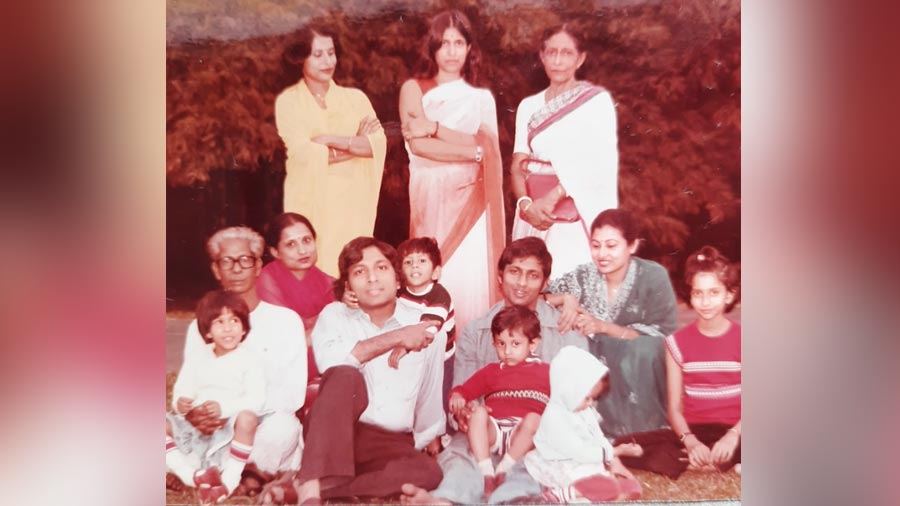

Das Sarma (extreme left) at the Botanic Garden in Shibpur, in 1981, with his family

Dinajpur and Balurghat

He founded a club in 1945 – Polestar – which looked into Hindu-Muslim conflict in the area – the stirrings of which were only felt after news of the Radcliffe Line (demarcating India and Pakistan) filtered down. “But we did not actually feel any communal tension,” he confirms. He goes on to recall that Dinajpur was also protected from the Bengal Famine in 1943, being far away from the towns near the river where crops were being destroyed to keep the approaching Japanese at bay. “We had a lot of rice in fact, and we even hoarded some because we knew there was a famine in Bengal,” he recounts.

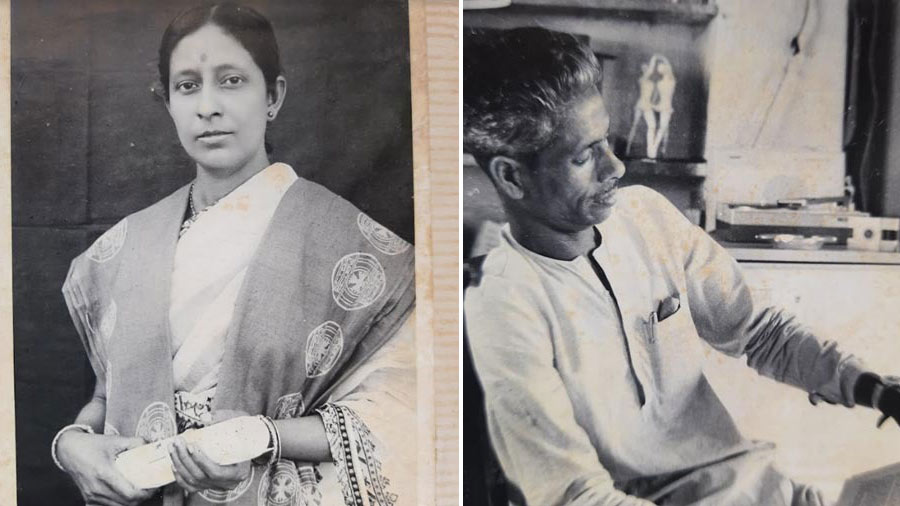

Even though the people of Dinajpur remained relatively unscathed in the upheaval of Independence, Das Sarma moved to Balurghat in 1947, skirting the edges of Bangladesh. He married a young girl, Bina Sen, who used to visit the house because her sister was married to his eldest brother. Bina managed to fulfill for herself what her husband had been unable to do – procure a college degree. After a degree in Bengali from the University of North Bengal, she also completed a degree in Library Science from Jadavpur University. She went on to become a librarian in Dinajpur, where she would lure her sons to study by promising them an irresistible combination of bonde and jhuri bhaja!

Nirendra Nath Das Sarma and his wife Bina Sen, who was secretary of the Agrani Mahila Samiti in Balurghat till they moved out. Das Sarma helped his wife with accounts before the annual auditing

Three sons and a daughter were born to Bina and Nirendra Nath. “It was my mother who was charismatic, but I remember my father to always have been hardworking and sincere,” says their son Abhijit Dasgupta, who is now retired from the merchant navy. His father used to keep a strict schedule, where he’d be in office at 8am and return for lunch, after which the children wouldn’t see him again until 9 at night. On the days he’d volunteer to sit down with homework, he was prone to losing his temper with his truant sons, which only made his wife annoyed with him for running low on patience. “But when it was time to go to bed, it was Baba who would fan us until we fell asleep. We didn’t have electricity in the house in those days,” reminisces Dasgupta.

Nirendra Nath Das Sarma — steeped in his books all day

At his desk, 12 hours a day, except for IPL breaks

Even now Das Sarma maintains a fairly regimented life. He’s given up on meat entirely, though he likes his fish, a regular supply of mishti and will occasionally overindulge the shukto. He is often seen working at his desk for 12 hours a day, poring over history texts and making notes for himself, with pens he likes to choose himself. He insists on a particular kind of refill instead of just replacing an old pen with a new one as is the custom these days. Sometimes, when Snoopy the beagle can’t distract him from his books, a riveting game of cricket can. In fact, he finds IPL particularly exciting.

“My back will give out if I sit in one position for so long… sometimes I feel like I’m the one who's a hundred years old!” laughs Dasgupta, and one is forced to draw humorous parallels to Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles.

Das Sarma with his son Abhijit Dasgupta

Das Sarma also manages to make his son, who is almost seventy, feel like an irresponsible teenager. “I find myself still having to answer to my father about where I am and how late I might be!” exclaims Dasgupta. Once a parent, always a parent. The tables here remain unturned, for Das Sarma himself likes to remain noncommittal about his whereabouts — his family have returned home on more than one occasion to find that he’s slipped out to take a stroll around the Golf Gardens neighbourhood, and then he bristles upon being scolded.

Das Sarma flanked by his son, his daughter-in-law Vibha and the family beagle, Snoopy

‘I am not going to die,’ he wrote

Das Sarma did in fact have a brush with death. In 2012, what seemed like a minor breathing issue spiralled into various complications in the hospital. In the throes of his rapid decline, he was able to communicate with his family only in writing. “I am not going to die,” he wrote in trembling handwriting. Weeks later he emerged from the ventilator and insisted on being brought home, and it was at home that he slowly regained both strength and speech.

These days he watches the events of the world unfolding with an air of disbelief. He proposes two solutions to the country’s abiding problems. “Population control and education. Once enough people have been educated, the population problem will sort itself out. These days, even I find it hard to grasp all the new developments. I can't imagine how hard it must be for the illiterate and the poverty-stricken.”

He recalls visiting Jodhpur Park (now a bustling neighbourhood in South Kolkata spilling over with cafes) years before he moved to Kolkata in 1977, and being struck by how bare the surroundings seemed to be. The same area, 2km away from where he now lives, has become unrecognisable to him.

(Left) Bina Sen passed away in August 2016 at the age of 92; (Right) Das Sarma moved to Kolkata in 1977 and eventually retired from his post at the Calcutta Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA)

What would he have done differently if he’d known he was going to live for more than a hundred years? “I would have learnt computers if I knew I was going to live this long.”