The evident Ramzan story is about going drinkless and foodless for 14 hours.

The latent Ramzan story is about living a life – for a little over four weeks – in contrast to custom.

This could well be the biggest message of the month. Adapt. Change gears. Do more with less.

Consume less: There is no breakfast, brunch and lunch. The counter-argument could be ‘But there is the sehri and a lavish iftar.’ My regimen: the sehri comprises two bananas, muesli (teen mutthi) in milk and one bottle of water. In a normal month, this would have been a ‘prep’ for breakfast. I need to live on this diet until 5.47pm. This ‘more with less’ could possibly have something to do with a muted table lamp, soundless neighbourhood and sweeping darkness. Even turning to a second bottle provokes the insides (‘Aur kitna paani piyega?’)

Killing desire: A prominent Ramzan spinoff is a decline in desire. This does not transpire immediately. However, by the end of the first Ramzan week, one is at peace with the world by 6.30 pm. There is no desire to engage. A standard excuse helps me skip social engagements. The desire is to do one’s own thing, which means disappearing into a corner and reading a book (which enhances my respect for all those who venture for evening prayer or Quran reading).

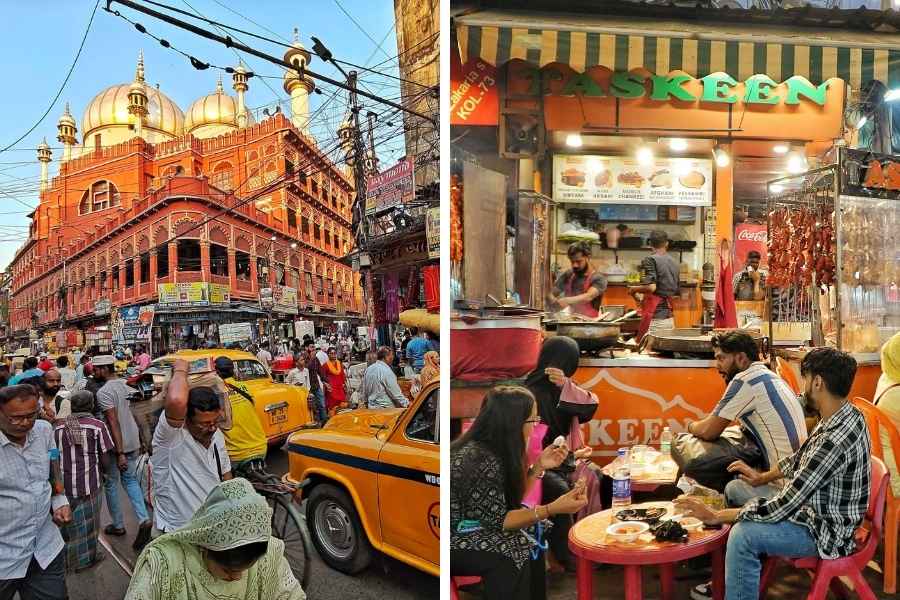

Flexibility: Ramzan is about flexibility. I would normally rise at 5.30am. I now surface at 3.30am (Dalai Lama time). I slurp on sehri and proof-read concurrently. I force-awake myself until 5am (time for the morning prayer) when I can ‘speak’ with my Maker. I sleep thereafter to rise at 8am (unless interrupted by the need to de-bladderise, which is increasing the older I get). I sleep an hour each afternoon. This is my unworthy Ramzan adjustment. Most Muslims pray five times in the masjid. Most Muslims spend three hours at taraweeh readings each evening. Most people keep flitting between dukaan and masjid every two hours. For this month, pre-set schedules are rescribbled; Ramzan alone dictates.

No travel: If you travel, you miss a day (or days of fasting) on account of time differences or by invoking the fasting exemption when changing geographies. One skips travel during Ramzan. One discovers ways of getting clients to say ‘Oh you are fasting? Then can we finish our meeting on the phone?’ I have begun to use the Ramzan shield for commutes as well. The same line works as effectively if someone wants you to travel 15km for a 10-minute meeting.

Energy foods: When we were younger, less wealthy and less spoiled by choice, there was a family focus on energy iftar foods. Some of the things that we would nibble during that one month we would never eat for the rest of the year. These began to get known as ‘Ramzan wala chana’, ‘Ramzan wala sufoot’ and ‘Ramzan wala dal.’ A similar commitment to energy spikes would be forgotten as soon as the Eid prayer concluded.

Normalise: The Ramzan challenge lies in getting through the work of the day as if nothing has altered. For just about everything that the month warrants from mortals, there is a change or adaptation except one: ‘business as usual.’ Day after day. The shop must open on time. You need to swipe your card in at 10. You need to address family needs the way you did. The world doesn’t care if your only permitted resource is oxygen.

Giving: Ramzan comes with a belief. The Maker magnifies the ledger impact of anyone who donates this month. Muslims are smart; they dispense their zakat — alms calculated at 2.5 per cent of wealth — in Ramzan for the multiplier book entry. Homemakers pass the word around on who could be a recipient for the food rations to be given out (which is ironic because if the recipients are likely to be Muslims, then they would be fasting and eating less). One presumes that Ramzan increases foodgrain giving and inventorisation, only to be consumed in the later months. The sad part is that the same liberals seldom contribute cash or kind in the other months, but not a word of that here.

Overcoming a hump: This is another achievement biggie. The bogey (Urdu word ‘havva’) starts building a fortnight before: ‘Ramzan is coming.’ It is like that winter in Game of Thrones: to be feared. By the eve of the Great Month – that last breakfast – the image has been built of the mountaineer who looked up at the peak from Everest Base Camp and wondered ‘How will I ever…’ For all those who step into the first day unintimidated, chip day after day at the edifice, and tell others ‘This too shall pass’, I bow to them. They should be appointed life counsellors.

Un-TV, un-music: There was a time (during a modest existence in Mission Row Extension) when the matriarch’s ruling was ‘No TV, no radio.’ For a month, Kishore Kumar would be stilled; the only time the TV would be permitted would be to see Test match highlights (after a fervent arzi that this did not constitute ‘entertainment’). Rules have slackened. Despite no matriarchal policing any longer, there is virtually no music (even though I must concede and confess some Paatal Lok 2 is snatched in between burps for a mood change) at home during this month. It wouldn’t feel right.

No hair oil or Colgate: This will surprise. I grew up in a family, where, if the mother decreed that there would be no Navratna on the scalp or powder under the armpits or perfume in line with a larger spirit of enforced austerity, then so it was. When I mentioned this to my friend Iftekhar the other day, he was surprised. He used attar on his sleeves alright during Ramzaa, but added as if to compensate: ‘I don’t use Colgate.’ We Muslims need to speak with each other more often.

Testing the body: I call Ramzan the ‘Thermostat month’. How will you know whether your body is resilient unless you test? How will you know that you still have some semblance of the camel DNA from your Paleolithic ancestor unless you dare? How will you convince yourself that ‘I will last it’ if your aircraft crashes in the Andes and the reconnaissance team is still a week away? I won’t say I won’t quiver in the sub-zero, but I will keep telling myself ‘Relax, just pretend it is four rozas back-to-back.’

Sounds: I do not live in a Muslim neighborhood, so cannot testify about the muezzin’s capability. But Shaheera told this: ‘I go each evening for taraweeh and there is this young man who recites there – no musical accompaniment obviously – and he moves listeners. When he recited Surah Ikhlas, most of the assembled were in tears. Just words. Just tune. Just throat. And he took you to another level.’

Winning mind battles: Ramzan is a mind battle. The fasting does not trouble. Lailatul Qadr does. It is that date of the month when the faithful need to be in prayer through the night until the lower arc of the sun rises completely above the horizon. Which means: no sleep, not even a nap, not even lying down (matriarchal diktat). In non-Ramzan circumstances, this would have been like a night out with friends when no one wanted to return home. Except that after you have consumed your iftar and downed barley water, the body slips into rebellious ‘go slow’ from 6.15pm for a journey that is to last until nearly 6am. The mind starts playing games (‘Oh, this is going to be a long night, so skip it this year, just this year’). The 11.30pm seductive whisper is ‘Go and pray the rest at home’. The post-sehri 3.30am Satan won’t accept defeat (‘You’ve almost won, you deserve a nap, you’ve earned it.’) At 5am, Satan unleashes all weapons of isolated destruction (‘Ahh, that sweet taste of the light sleep, how I could caress you with it, if you just step into my arms, my child’). Mom, I hit the bed only at 5.49am this year. You won.

If Ramzan were just three months a year, the poor would not go hungry, food would be abundant, fruit growers would climb out of poverty, farms would be converted into forests, vehicular and air travel pollution would decline, the world would decarbonise, the desire industry would seek a government bailout and savings would rise.

I have another sneaking feeling. We might even be happier.