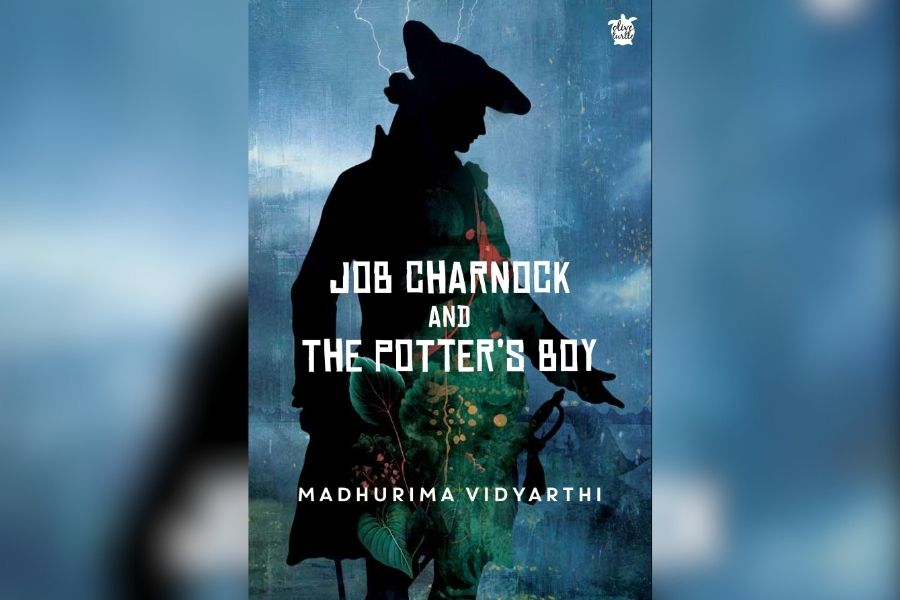

Set in the 1680s, during the waning years of Aurangzeb’s rule, Madhurima Vidyarthi’s novel, Job Charnock and the Potter’s Boy (Niyogi Books), is framed around the life of Jadu, a 12-year-old potter’s son who becomes an inadvertent witness to history. He is drawn into the political and emotional whirlpool of an area in transition — a Bengal that is on the verge of becoming centred around Calcutta — after a personal catastrophe forces him to leave the humble life he has known.

The novel is not a historical epic, but a quiet reorientation of history. It does not bluster across timelines or trumpet colonial conquest. Rather, it hears the sounds that are below the surface, such as the disintegrating world that a youngster inherits, the silence of tidewater, and the snap of wet mud. In doing so, it offers one of the most poignant fictional engagements with early colonial Bengal in recent memory. Job Charnock and the Potter’s Boy is not concerned with simple dichotomies of coloniser and colonised, or empire and resistance. Unlike many historical books, it does not romanticise a city’s origin story. Vidyarthi adopts a different strategy, using the perspective of a kid who lacks a set language to understand the gradual and frequently violent changes occurring around him.

At the age of 12, Jadu witnesses the demise of his parents who were innocent bystanders in the conflict between the East India Company and the Nawab of Bengal. His entire existence is upended by this moment, which puts him in survival mode. This adds a certain layer of silent compassion to the story. Jadu does not judge or interpret. He observes, absorbs, and endures. Ever as he finds himself entangled in a flurry of events.

Jadu stays at Sutanuti from December 1686 to February 1687, and spends a lot of time on the river. He then travels from Sutanuti to Hijili and again to Sutanuti, until March 1689, when he finally meets Job Charnock, the man responsible for his tragedy. It is at this point, however, that the plot slackens a bit.

A portrayal of history through the lens of the grassroots

Some readers may also find themselves wanting more complexity from secondary characters, a deeper sense of inner life from those who surround Jadu. At times, the writing leans too heavily on historical exposition. But these are minor notes in a novel that largely succeeds in its vision.

What Vidyarthi accomplishes with precision is the portrayal of history through the lens of the grassroots. The East India Company is present, but it does not occupy a central position. Job Charnock is not the protagonist. He appears at the periphery — opaque and inscrutable — a man with power but little emotional dimension. This deliberate narrative choice serves as an act of reclamation, reminding the reader that history, though narrativised by power, is essentially about the marginalised.

Job Charnock discovers Sutanuti by accident, but he is so enthralled by the location’s tactical possibilities that he challenges the Nawab’s troops in full force. It is as much a tale of incredible guile and greed as it is of unwavering perseverance and resilience. But the book is not about Charnock as a historical figure. Rather, the focus is on the effects of his actions, which ripple through the lives of those least documented — artisans, boatmen, traders, widows, children. Charnock’s impact is shaped not only in courtrooms or treaty halls, but also in kitchens, riverbanks, and potter’s sheds.

When Jadu watches the river shift its banks or listens to the cautious murmurs of those around him, we sense how deeply lived histories are not linear, but ambient — absorbed into the textures of daily life. Jadu eventually becomes one of Charnock’s aides, but Charnock himself remains more of a distant presence than a dominant figure. It’s through Jadu’s gaze that Charnock’s strategies and ambitions unfold, making him a catalyst rather than a hero.

Reconstructing a forgotten chapter of Bengal’s colonial past

Vidyarthi’s strength as a writer lies in providing mundane yet sensory details without being ornamental. In rendering texture such as the grain of clay under fingernails, the smell of damn jute, the dense stillness of humid afternoons, she evokes an atmospheric melancholy — not of despair, but of irreversible change.

The novel lingers on in gestures: a shared meal between strangers, the weight of silence in a crowded boat, the careful way Jadu learns to listen before he speaks. These moments acquire meaning slowly, much like the city that begins to rise around him.

In the ‘Author’s Note’ at the end, Vidyarthi states, “While trying to adhere to accepted chronology, the temptation to exercise creative licence is often too great to be overcome.” A significant character in this regard is Job Charnock’s wife, whose interactions with Jadu are symbolic of a coming-of-age novel as her death and his attainment of manhood are subsequently interwoven.

By juxtaposing imagination against historical events, Vidyarthi successfully paints a picture of the struggles that were never documented. She gives a voice to the rustic and unnoticed, reconstructing a forgotten chapter of Bengal’s colonial past.

The novel leaves behind no grand proclamations, only the silent echo of footsteps across soft, shifting earth. It reminds us that cities are not only built by men of power, but also shaped by those who carry clay, grief, and memory in their hands.