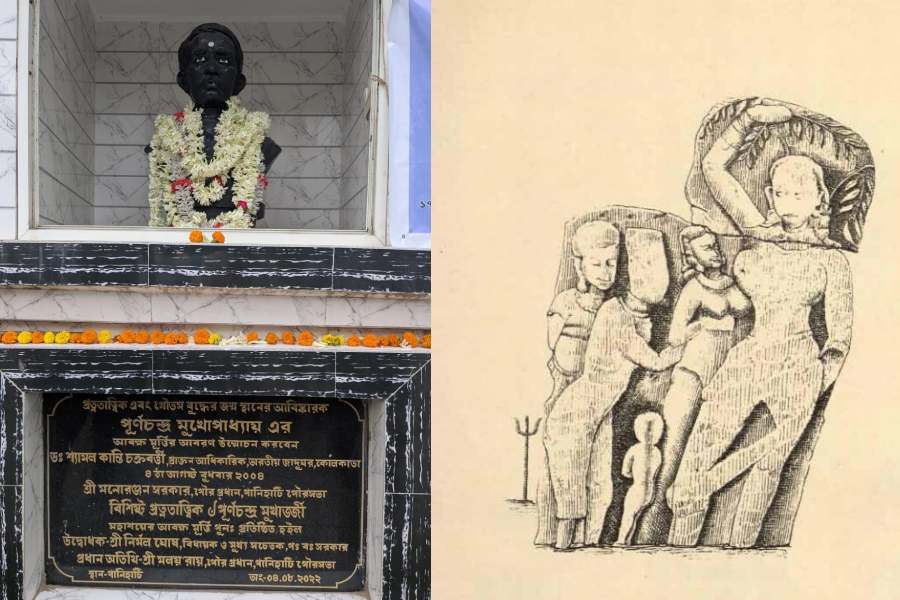

A dozen people peered into a glass case. Most of them had garlands in their hands. And inside the glass case, sitting in a brick-and-mortar kiosk on Panihati’s P.C. Mukherji Road, was a granite bust of a man.

The bust belongs to Babu Purna Chandra Mukherji, who is a pioneering Indian archaeologist, and the road — which is actually a strip of a lane — takes its name from him.

Those gathered are Mukherji’s acolytes — teachers, lawyers, local historians and heritage enthusiasts. They get together every year to offer tribute to the polymath from their neighbourhood.

Mukherji lived here, and died here when he was 53 years old, in his ancestral home named Kapilavastu. Today, an apartment block stands on the space the 250-year-old mansion once occupied.

Mukherji might be an unsung hero in the annals of Indian history but his contribution is widely acknowledged in Nepal, Sri Lanka and several Southeast Asian nations where Buddhism has a robust following. He is revered in these countries as the archaeologist who unearthed several Buddhist relics, including the birthplace of Gautam Buddha.

Sekhar K. Seth, who is a heritage expert living in Panihati, says, “Except among archaeologists, Purna Babu’s unique contribution during the excavation of Buddha’s birthplace at Lumbini in Nepal, and the ruins of Kapilavastu, the palace where he grew up, remains a footnote in history.”

According to Seth, Panihati Municipality named the street after Mukherji soon after Independence, but most people still do not have any idea about Mukherji’s work and times. Two others from the neighbourhood, Koushik Paul, who is a school teacher, and Anirban Ghosh, who teaches Chinese at the University of Wardha in Maharashtra, have taken up the task of raising awareness.

When the archaeology department of Nepal celebrated the 175th birth anniversary of Mukherji last year, they invited Ghosh and Paul to deliver talks on his early years. Ghosh has been in touch with archaeologists and academics at Nepal’s Kapilvastu Museum and Lumbini Buddhist University; both of them have also been working on a collection of essays on Mukherji for the last 10 years.

Mukherji was considered no more than a “petty draughtsman” by his British bosses at the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). A draughtsman, or draftsman, was required to make technical drawings related to archaeological findings and sites. According to Gautam Sengupta, who is a former director general of the ASI, Mukherji was recruited for the North-Western Provinces and Oudh Circle. The circle, which roughly corresponds to present-day Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, was a significant area for historical and cultural sites. Says Sengupta, “Notwithstanding his designation, Mukherji also led several expeditions in the forests of the Terai region and excavated a number of archaeological remains of the Mauryan and pre-Mauryan period.”

Archaeologist and writer Dipan Bhattacharya, who is based in Noida in UP, and is working on a commemorative volume on Mukherji, says, “I have dug up details of his research, his excavations and his field notes.”

According to Bhattacharya, apart from the relics related to Buddha’s birthplace, Mukherji discovered the remains of Pataliputra, which used to be a centre of political, economic and cultural activity in ancient India. “In 1901, he conducted archaeological excavations at Champaran, Darbhanga, Gaya and Shahbad and unearthed several ancient epigraphs. Later, he travelled to Bhagalpur, Burdwan and Baleswar for archaeological expeditions,” Bhattacharya adds.

Mukherji had written down the details of his expedition in Nepal. He had toured the geography instructed by Vincent Arthur Smith, a British Indologist, historian and a member of the Indian Civil Service. That was in 1901. Mukherji wrote: “There is no road in any direction… nullahs and streams are seldom bridged. The cart track is so circuitous… the forests are full of wild animals… as I found one tiger almost attacking me one day near the ruins of Tilaurakot.” Tilaurakot is in southern Nepal.

Smith was the rare British boss who appreciated and recognised Mukherji’s pioneering work. He wrote in the introduction to Mukherji’s report, “...considering the obstacles in his way and the shortness of the time available, I think that Mr Mukherji did very well. His map is quite accurate enough for all practical purposes, and is of great value.”

Mukherji had started his career as an artist and illustrator. He had studied fine arts at Canning College in Lucknow, after which he joined Lucknow Museum as a draughtsman. The museum authorities sent him to the J.J. School of Arts in Bombay for further training.

Mukherji went on to record the glorious art and architecture of Lucknow eventually in a book titled The Pictorial Lucknow: History, People and Architecture. He wrote in its introduction, “Is the past history of Oudh so despicable an affair that no lessons can we derive therefrom for our future guidance? Is there nothing in the dying local arts, especially architecture, which requires enquiring into, and which deserves encouragement?”

Colonial historian Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, who has been writing on Lucknow, its culture and its rulers, from the 1970s, tells The Telegraph, “P.C. Mukherji’s Pictorial Lucknow published way back in 1873 is an important book to understand the city, its people, its art and architecture.”

Bhattacharya believes Mukherji was an archaeologist way ahead of his time. He says, “In the early days of archaeological studies, he had made some outstanding excavations. He even wrote succinct reports whose revelations were proven true in later years when archaeological studies combined with modern technology such as radiocarbon dating.”

Adds Anirban Ghosh, “Despite his monumental achievements, Mukherji spent his last days in abject poverty.” He adds, “Perhaps his contribution was ignored by the authorities and the people because of his strong swadeshi views.”

By that logic, this ought to be Purna Chandra Mukherji’s coming of age in India’s public memory.