Poila Boisakh or the first day of the Bengali calendar year is based on Bangabda or the Bengali year.

British administrators in India used the Gregorian calendar based on the astronomical solar cycle from the middle of the 18th century. After Independence, India decided to stay with the Gregorian calendar for official work, but there were public holidays based on local festivals and these were calculated according to indigenous calendars.

But when the first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru realised there were 30 different astrological almanacs and too many date-management systems, he set up the Calendar Reform Committee in 1952 and appointed astrophysicist Meghnad Saha to head it.

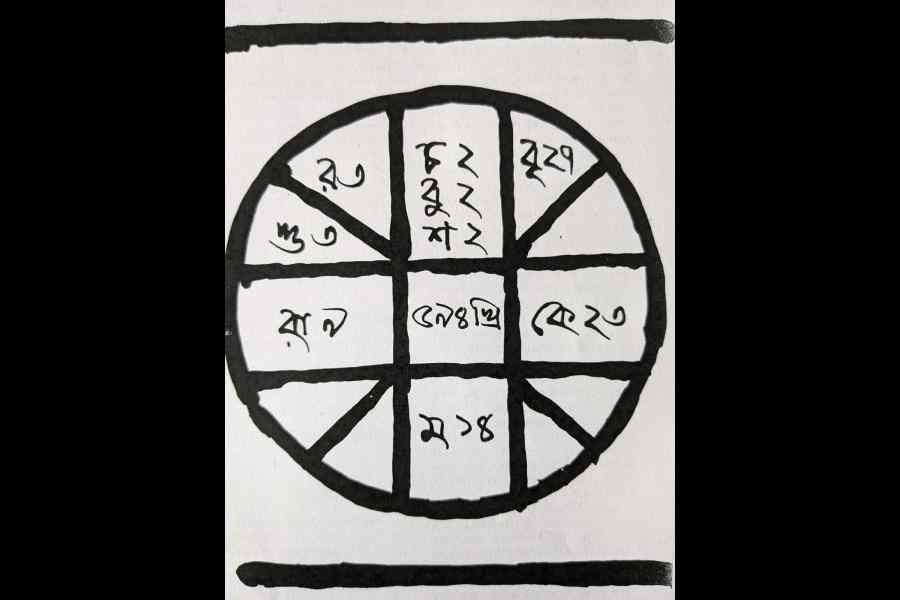

Almanacs or panjikas are annual publications that contain tables of astronomical and astrological events for the coming year. Calendars are based on almanacs. Panchanga is the term for a Hindu calendar and almanac.

The majority of the regional calendars and almanacs are based on ancient astrological calculations that focus on the navagrahas or nine planets, including the mythical demons Rahu and Ketu, who are believed to devour the “planets” sun and moon during eclipses. Among the almanacs, very few follow the scientific calendar based on positional astronomy. The Bisuddha Siddhanta panjika is one such.

The most popular ones such as Benimadhab Seal, Gupta Press and P.M. Bagchi (Bengal), Kalpurush Purnanga, Kalchakra Purnanga, Borkotoky (Assam), Biraja, Kohinoor Press (Odisha) follow a method of calculating days, months and years that is based on astrology.

The Saha committee suggested the creation of a scientific almanac based on accurate and modern astronomical data.

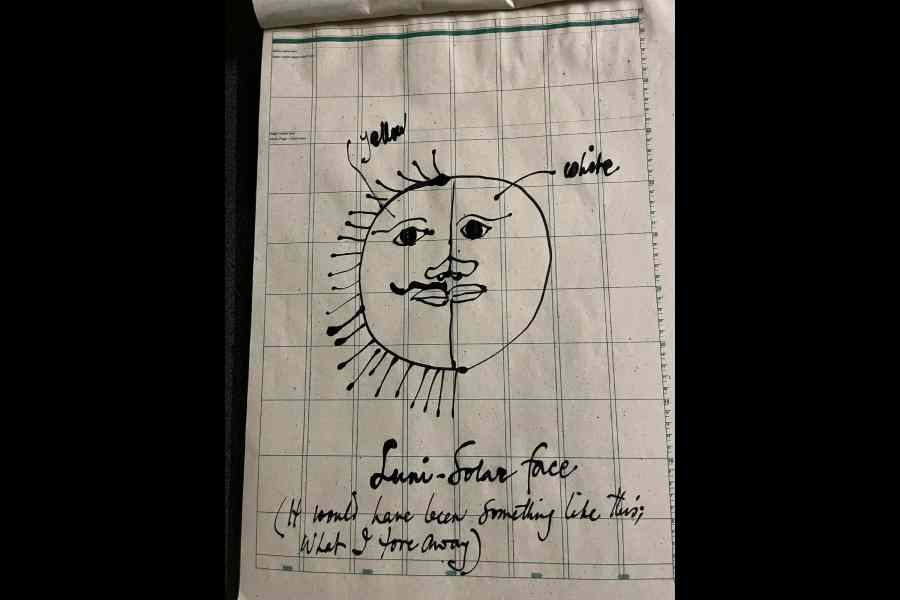

The committee asked for the preparation of the Rashtriya Panchanga, also referred to as the National Calendar of India. It was to use the new calendar system for official purposes and a lunisolar calendar system for socio-religious purposes. Lunisolar refers to a combinationof lunar and solar cycles.

Later, it was decided that work on the National Calendar of India should be undertaken by a special unit attached to a scientific research department of the Government of India. In the 1970s, the Positional Astronomy Centre (PAC) was founded in Calcutta to continue this work.

But there were many issues to work around. For one, most traditional Indian calendars are based on the solar year as calculated by Aryabhatta around 505 AD. The ancient seer was obviously not aware of the precession of vernal or spring equinox — the day the sun is directly above the Equator. As a result, the length of the year as calculated by Aryabhatta was not accurate. Regional calendars observe the vernal equinox on either April 14 or 15, based on his astrological calculation. But astronomical calculation has proven that the vernal equinox falls on March 21.

“To correct this error, the Saha committee recommended that the first month of the year be Chaitra and its first day should be March 22,” Chandan Mazumdar, who is a senior professor at the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta, tells The Telegraph.

But scientific recommendations haven’t been accepted all around, not by the orthodox panjika makers nor the traditional panchanga makers, nor by the common man. This occasionally leads to quarrels. But this year, all have unanimously accepted that we are about to step into the Bengali year 1432 on April 15.

Swapan Kumar Thakur, who is a writer and researcher of folk culture, says, “Bengal had a variety of calendars, many of which were attributed to various kings, such as the Saka ruler Kanishka, Sashanka, Chandragupta II, Lakshman Sen, Bakhtiyar Khalji and Husain Shah.”

The Hindu Sen dynasty rulers introduced the Saka era calendar in Bengal in the early 12th century. Writes Thakur in his recently published book Bangabda o Boisakhi Banga, “We can find mention of Sakabda in several epigraphs on Bengal’s terracotta temples.” Sakabda means Saka year.

In 1203, Bengal was captured by Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turko-Afghan military general who established himself as the ruler of Bengal and parts of eastern India. He introduced the Islamic calendar known as Hijri for official purposes, but Hindu Bengalis continued to use the Sakabda. Although other Muslim rulers of medieval India imposed the Hijri on their subjects, Mughal emperor Akbar decided to break away from the lunar calendar system. He believed it was “inappropriate” for India.

It was he who created a lunisolar calendar — called Tarikh-i-Ilahi in keeping with his pragmatic views. Says Mrinal Kanti Pal Ray, a former director of PAC, Calcutta, “In Islamic or Hebrew calendars, an extra month is added every few years to keep the lunar months aligned with the seasons.” Akbar’s calendar was also to synchronise with the principal harvest season across India in the month of Chaitra.

Akbar wanted to make the revenue system more efficient and organise tax collection at the end of spring. The new calendar year known as Fasli, most likely after fasal or harvest, was fixed on March 21, the date of vernal or spring equinox. It was introduced across India in 1584.

Bengali pundits, who had been unhappy with the lunar Hijri calendar that never agreed with indigenous calendars, accepted Akbar’s calendar. But, they tweaked it based on the Surya Siddhanta, which is the “astronomical text” on which the panjikas are based. Instead of accepting March 21 as New Year’s day, the pundits opted for mid-April.

And that is why Poila Boisakh in Bengal, Bohag Bihu in Assam and Pana Sankranti in Odisha, the first days of the respective indigenous calendars, are in April and not March.

The mosaic of regional cultures represents the wonder that is India. People follow the Gregorian calendar for all official work. January 1 is celebrated as New Year’s day, like in the rest of the world. Yet we wear new clothes and feast on traditional delicacies while wishing each other Shubho Nabobarsha in mid-April.