A short story, written in the Sixties by Raj Chatterjee should perhaps be made compulsory reading for judges.

The story was about a judge, a hakim, who reached a remote village to hold a camp court. On the very first day, he came across a land dispute between two families, which had lingered for several generations.

The dispute often sparked violence and several members of the feuding families had lost their lives. The judge listened to the arguments and counter arguments; went through the facts and posed searching questions. Finally he asked both the parties if they wanted him to give a ruling and end the dispute once and for all. When both parties agreed, he sought the original documents related to the dispute to peruse personally.

That evening, the hakim sahib returned to the tent, had his bath and sat down with a drink by the side of a fire that was lit. He called for the files and then, one by one, set all the original documents of the case on fire. His khansamah reminded him that the sahib must have thought of the consequences of his action. The sahib smiled and said the law was meant for the people and not the other way round. The documents were at the root of the litigation but with all of them gone, the feuding parties would have to accept his ruling, which, he assured his khansamah, would be equitable.

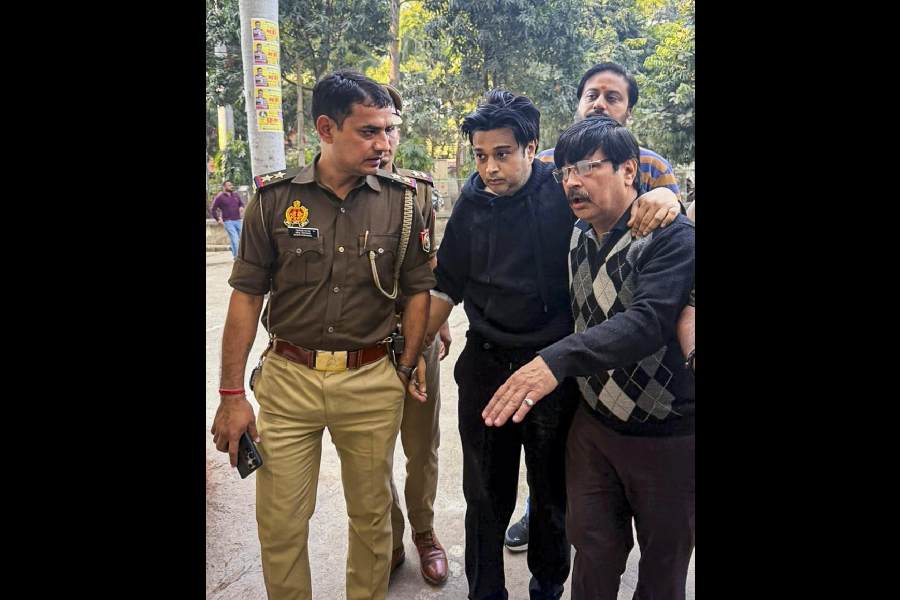

A fable or a fairy-tale, we are reminded of the story by the ongoing travails of Shibu Soren. In three different cases, he stands accused of jumping bail. He is accused of violating prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the CrPC in Jamshedpur and not appearing before the court. The section prohibits assembly of more than five people. The FIR, however, names three people in all, including Soren, and several hundred “unknown” people. One presumes that the two other lesser mortals, named in the FIR along with Soren, have either been punished or will be hounded once the police nab their prize catch.

The five-year- old case must have been rather serious for the Jamshedpur police to rush a team to Jamtara with a warrant! The court, however, is unlikely to ask why the police cannot sleep over the case for 10 more years, if they could do so for the past five.