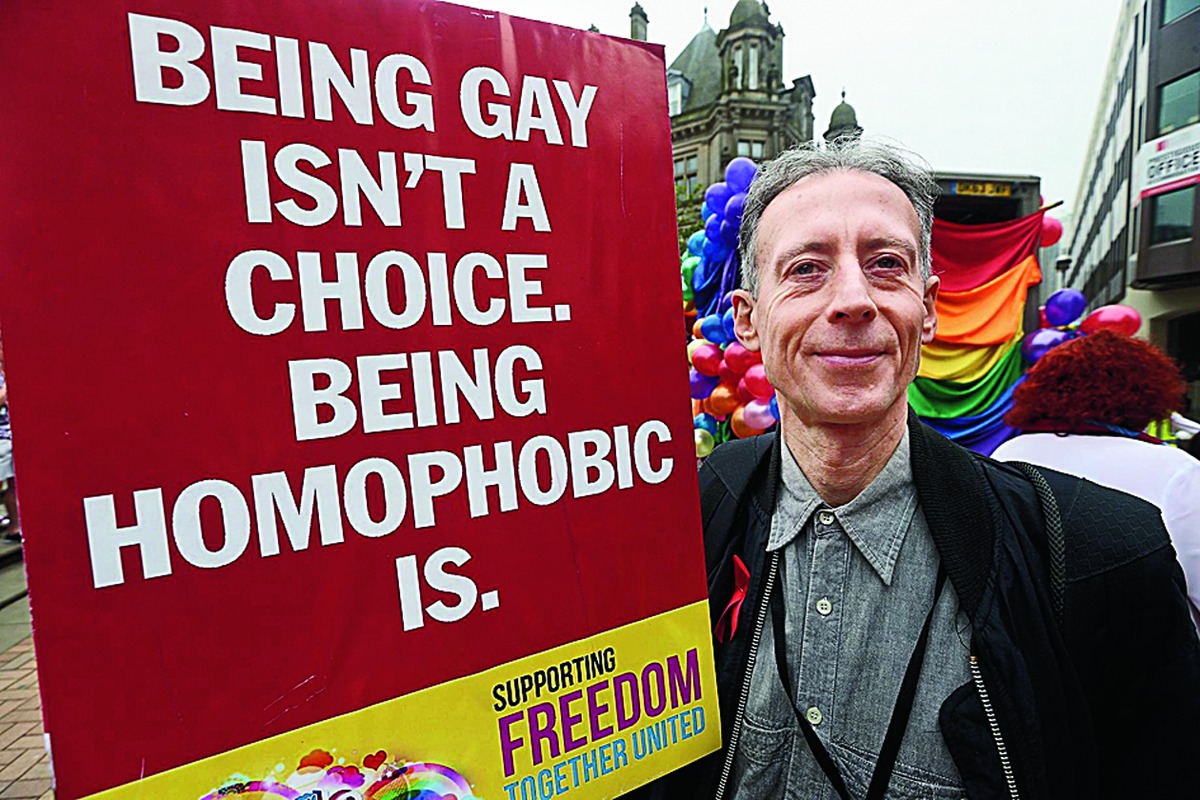

London: Britain's leading gay rights activist Peter Tatchell told The Telegraph he was "delighted" with the Indian Supreme Court's ruling on Section 377 that BBC news bulletins featured prominently as a "landmark judgment".

"I am delighted that the Indian LGBT people in their long struggle have finally got the result they wanted," he said on Thursday after the court's verdict decriminalising adult, consensual gay sex in private.

Asked whether India should now follow the example of Britain, he pointed out: "Till 1991, Britain had the worst laws of any country in the world, some dating back to the last century. "Today we have some of the best laws - it has been the biggest, fastest reform in Britain's history."

Some Indians, such as the author Zareer Masani, have said they left India because they were not free to live as they wished in India, although he did admit in one radio programme that the climate was no longer as rigid in Bombay as it had been when he was a schoolboy.

Today, in modern Britain, it is not unusual to see public displays of affection between couples of the same sex, say, at railway stations. But it was not always thus.

After decades of prosecution, the big change came with the Sexual Offences Act 1967. This stipulated that private sex acts between consenting men over the age of 21 would no longer be a criminal offence in England and Wales, although Scotland did not follow suit until 1980 and Northern Ireland until 1982.

In 1988, Margaret Thatcher, then Prime Minister, had provoked a backlash when she introduced an amendment to the Local Government Act 1988 banning state schools from teaching or promoting the "acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship".

"Section 28" caused widespread outrage and served as the catalyst for a massive surge in gay activism, including the formation of the LGBT rights group Stonewall UK. Section 28 was repealed in Scottish law in 2000, and from English, Welsh and Northern Irish law in 2003.

In 2004, the Civil Partnership Act allowed same-sex couples to enter into same-sex unions with the same rights as married couples.

In 2014, the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013, which recognised same-sex marriages, entered into law in England and Wales. Several gay couples married at the stroke of midnight on March 29, 2014, when the law officially came into effect. This was hailed by David Cameron as his greatest achievement as Prime Minister.

Scotland legalised gay marriage in December 2014. Gay marriage remains illegal in Northern Ireland - a point of contention because Theresa May depends on 10 MPs from Northern Ireland's Democratic Unionist Party for her Commons majority.

Tatchell, 66, who has long been prominent in the fight for LGBT rights, said carefully: "Indian people have to choose their own course to secure LGBT freedoms. But of course I hope that what has happened in Britain and other western countries will inspire India."

Even before The Telegraph contacted Tatchell, he had been quick to tweet his reaction to the news from India: "Historic news! India's Supreme Court has decriminalised homosexuality. This ruling sets free from criminalisation almost one fifth of the world's gay people. It is the biggest, most impactful gay law reform in human history."

He followed his interview by sending The Telegraph his considered statement which added: "I hope it will inspire and empower similar legal challenges in many of the 70 countries that still outlaw same-sex relations, 35 of which are member states of the Commonwealth.

"Ending the ban on homosexuality is just a start. There are still huge challenges to end the stigma, discrimination and hate crime that LGBT people suffer in India.

"Indian LGBT citizens now revert to the legal status of non-criminalisation that existed prior to the British colonisers imposing the homophobic Section 377 of the criminal code in the nineteenth century."

The Telegraph also contacted Stonewall, which plays a leading role in campaigning for the equality of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people across Britain.

Leanne MacMillan, Stonewall's director of International Campaigns, commented: "This is truly wonderful news and a massive step forward for our lesbian, gay and bi siblings in India.

"The momentous ruling comes after nearly two decades of hard-fought campaigning by Indian LGBT organisations and activists, and today we are all celebrating their success. We hope this historic moment will renew the fight for LGBT equality worldwide.

"Our work will not be finished until lesbian, gay, bi and trans people everywhere are accepted without exception."

No account of the fight for gay rights in the UK would be complete without recalling the jailing of the writer Oscar Wilde. His ill-advised attempt to sue the father of his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, for publicly accusing him of being a "sodomite" resulted in Wilde himself being put on trial.

He was convicted of "gross indecency" with Douglas under the 1885 Act, and sentenced to two years' hard labour - the maximum sentence allowed by the law. Physically ruined by the harsh prison regimen and impoverished by legal fees, Wilde died in 1900, three years after his release.

Prosecution of gay men has been far more aggressive in the UK than it has ever been in India.

The "Alan Turing law" is an informal term for the law in the United Kingdom, contained in the Policing and Crime Act 2017, which serves as an amnesty law to pardon men who were cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outlawed homosexual acts. The figure is about 50,000.

Turing, one of Britain's most brilliant mathematicians, was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts. Turing died in 1954, 16 days before his 42nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning. In 2009, Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for "the appalling way he was treated".

The Queen granted Turing a posthumous pardon in 2013.