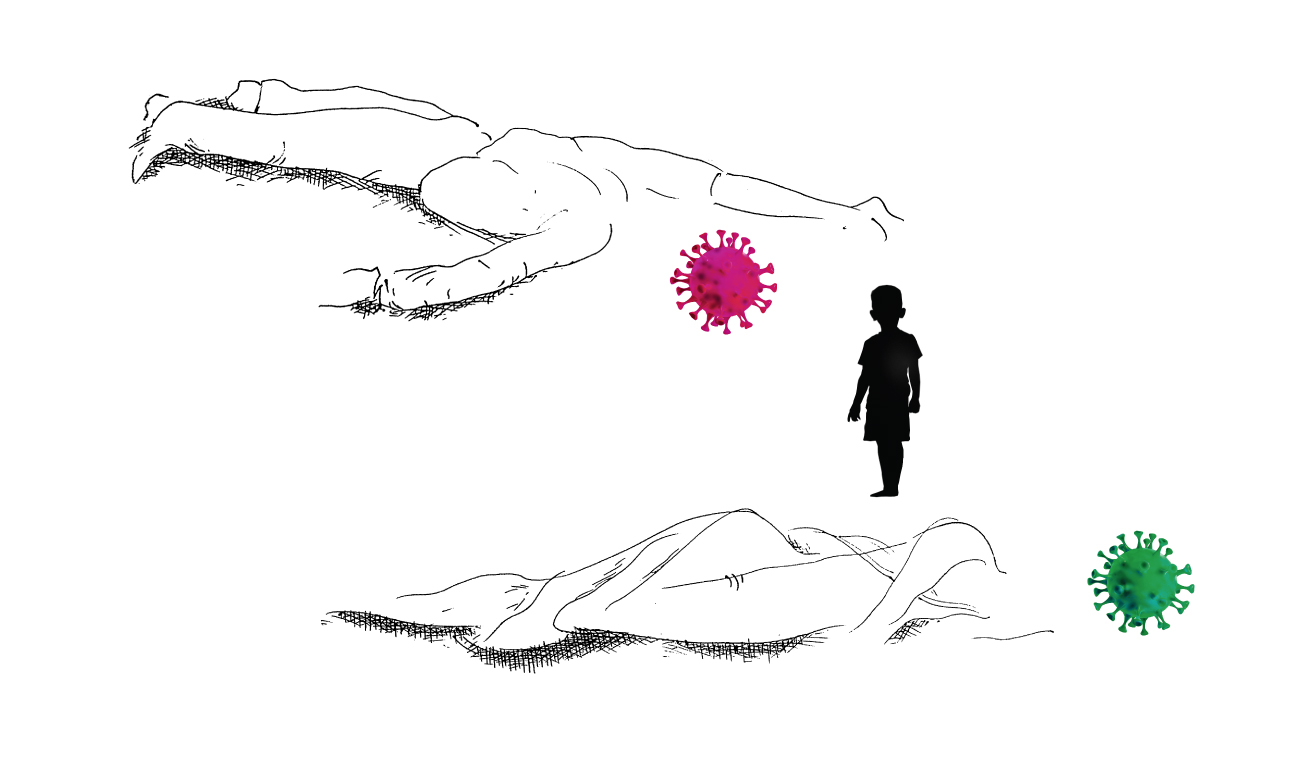

The first time it flashed on the phone, it seemed like fake news — an image of two toddlers orphaned after they lost both parents to Covid-19. Tough to tell the truth about that one, but shortly thereafter came a message on the school WhatsApp group. Someone was reporting how a close acquaintance of her mother’s had died leaving behind her 15-year-old son. The boy had lost his father eight years ago; this was a devastating blow. He was suddenly bereft, no parents, no grandparents, maternal or paternal. There were no close relations he could rely on either. He had no option but to go with the district child protection unit after spending a few days with neighbours who his mother had entrusted him with before she boarded the ambulance. That was the last he ever saw of her.

Soon popped up another case, a 19-year-old in Jaipur who lost both parents to the pandemic over the course of four days. His maternal aunt, a retired schoolteacher who lives in Calcutta, decided to take charge of the boy. “He is above 18 years of age. He is an adult but he is not a grown-up who can take care of himself or spend his life all alone, without any sense of belonging,” said Sumita Mitra (name changed), the aunt of the boy; she has applied for formal custody of her nephew.

According to Sheikh Jinnar Ali, national chairman of the National Anti-trafficking Committee, self-help groups active in rural Bengal have reported many such cases. “It was only last week that I heard of two cases — one of a two-and-a-half-month-old baby and another of a two-year-old girl. Both had lost their parents to Covid. In the latter case, when no one came forward to take responsibility of the child after both her parents died, the hospital informed the authorities,” Ali says.

Whether Covid does or does not hit children hard in the prophesied “third wave” is yet a matter of speculation. Meantime, the pandemic’s current, and second, surge has left many childhoods devastated. The West Bengal Commission for Protection of Child Rights (WBCPCR) has received distressing reports.

Says Ananya Chatterjee Chakraborty, chairperson of the WBCPCR, “There is a significant rise in the number of such cases where children have been affected — orphaned or left behind by parents when they have had to be admitted in hospital. We cannot yet confirm the number of such cases but it is much higher this year.”

However, what worries Chatterjee more than the phenomenon of Covid orphans at this stage is the fate of children being left alone or in the care of neighbours while their parents seek treatment. “It is those children whose parents are in hospital who need to be taken care of. One has to understand that many people in the country stay in one room. It is impossible for one member of the family to stay in quarantine. In those cases, we have reached out and helped,” Chatterjee says.

Similarly, a Bangalore-based NGO, Whitefield Rising, joined hands with specialist childcare NGO Dream India Network, Motherhood Hospitals, Rainbow Children’s Hospital and Mission Aahan Vaahan, a migrant evacuation initiative by the National Law School alumni, to open quarantine and Covid care centres exclusively for children.

Zibi Jamal, who is a member of Whitefield Rising, says that three quarantine centres (for boys and girls aged 6-11, girls aged 12-18 and boys aged 12-18) as well as Covid care centres for children between six and 18 months are being operated by Dream India Network. The centres can accommodate over 160 children at a time.

All of these started when reports of children being left alone at home as parents or the entire family needed to be hospitalised began to surface in early May. Jamal says, “We had issued an advisory for parents requesting them to identify the person who would look after children in their absence.”

The advisory said the parent should leave behind an information kit with essential details of the child’s needs and what may need to be done in case of an emergency. “It should have details like medication and allergies the child may have, contacts of the paediatrician or doctor, which school the child goes to, likes and dislikes and, of course, the contact numbers of relatives who can be reached out to if required,” says Jamal.

Chatterjee highlights more general, though critical, issues related to children. She says that since the onset of the pandemic, children have been silent, often unnoticed, bearers of consequences. “Schools have been closed down for an indefinite period, children cannot go out to play, they cannot mingle with their friends. Children have not been in good mental health for a while now.”

And then, of course, there is the issue of migrant labourers and their second dislocation in two years. “Loss of livelihood affects children adversely,” she says. Sonal Kapoor Singh, founder of Protsahan, a Delhi-based NGO, expresses concerns over the mass circulation of information of children being orphaned and that they have to be put for adoption. “We have received an Instagram message which says a two-year-old girl and two-year-old boy have lost their parents. More often than not, these messages are misleading or fake,” she says and adds, “We have informed the district child protection team and they are now looking into the matter.”

But what is worrying, according to Singh, is that such messages will only activate child traffickers. “Already the pandemic has jeopardised children to the extent that some have been pushed into transactional sex, which means these children are used as barter for food and other commodities. Such cases did come up when parents lost their livelihood or when a single parent, who was the sole earner of livelihood for the family, died. Child labour, child abuse and trafficking have increased.”

Singh is quick to point out that while fake news floats on social media, there is a genuine crisis with children and how they have been hammered by Covid; in the majority of cases, the truth does not surface or come to the notice of those who can help.

Dhananjay Tingal, executive director of Bachpan Bachao Andolan, says they have created a helpline number that beleaguered kids or their guardians can reach out to. “Between April 29 and May 12, we received some 416 calls. Of these, 10 per cent children were those who had lost both their parents and another 15 per cent who had a single parent and were in need of support,” he says. Most of the calls came from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh. “Respective state governments should take responsibility for looking after these children,” Tingal says. He adds, “No one should try to adopt a child without routing it through the Central Adoption Resource Authority. Many complain that the process in Cara is lengthy and time-taking. That is only because legal procedures are thoroughly followed. There is no risk involved — not for the child, not for the parents adopting them.”

Newspaper reports say that the Childline 1098 helpline recorded 51 calls between May 1 and May 12; all reported cases where children had lost both parents to Covid. The actual number of such cases will decidedly be far higher. For one thing, Childline 1098 is only one among several helplines. For another, not all cases get reported, the majority probably do not.

While organised and volunteer civil society groups have come forward to lend their support to Covid orphans, some state governments have begun to give focussed attention. The Odisha government reached out to its people to assist the administration in rehabilitating these children. This was shortly after a 45-day-old child was found sleeping by her dead mother in Ganjam district. The government opened a WhatsApp group with all village heads as they are the chairpersons of child protection committees at the panchayat level. Additionally, the Odisha government has announced free education and financial help to these children.

Delhi, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Karnataka have also taken steps for the rehabilitation of Covid orphans. A Twitter post of a 12-year-old girl and her younger sister standing by the graves of their parents probably brought home some of the poignancy of the unfolding tragedy. Help and attention will matter, it will rebuild the suddenly shattered lives of these children. But no amount of rebuilding will fill out the cracks Covid has already scored on their lives.