As I write this article, everywhere I look, there’s a scene of despair and helplessness. The dreaded second wave has brought down India to its knees. News channels, newspapers, social media are full of stories of death, shortages highlighting lack of medical infrastructure and pictures of agonised relatives watching or nursing their loved ones gasping for breath.

How did we get here? All of us are aware of the grave errors we committed during the early part of 2021, which has brought us to this road to perdition. I too have been thinking about how quickly we rebooted ourselves in 2021 and forgot the lessons the year 2020 tried to teach us. We forgot to take simple precautions, abandoned the golden rules of behaviour change (to prevent Covid from spreading) that we all knew, rejoiced too early and now we are beginning to pay the price for it. We learnt nothing but the more important question is why?

The ideas and practices we were supposed to adopt and maintain were simple. They may have been stifling but it required an acceptance of those ideas and we were expected to change our behaviour, for our own safety. Some of us adopted the ideas early on and maintained the behaviour change strictly, some completely negated the idea and never followed the rules. Most of us are between these two ends of the spectrum. As a behavioural scientist, my curiosity led me to ask a question: How does any new idea gain acceptance amongst public? Why has there been a seemingly lack of acceptance of ideas of behaviour change — masking up, avoid congregation, hand washing —amongst the significant proportion in our communities?

For example, we now know for more than 70 years that smoking causes cancer. This idea is not debated now, and it is accepted at a societal and community level. However, it did not happen immediately after the link between smoking and cancer was made. So, the question is how many Kumbh Melas, and election rallies will need to be held, before we, as a nation, realise that it is prudent to skip large congregations, in the face of such unprecedented humanitarian crises?

Of course, those in authority have spectacularly failed in propagating the ideas and leading by example. But on a broader scale, how do ideas of behaviour change diffuse across in communities/nations?

Diffusion versus dissemination

Social science tries to answer this question through the Diffusion of Innovation theory. It was developed by E.M. Rogers in 1962 and is one of the oldest social science theories. The theory attempts to explain how, over time, an idea or a product gains momentum and diffuses (or spreads) through a specific population or social system. Diffusion Theory attempts to understand the natural history of the spread of ideas and actions within social systems. The end result of this diffusion is that people, as part of a social system, adopt a new idea, behaviour, or product. Adoption means that a person does something differently than what they had previously done (that is, perform a new behaviour). The key to adoption is that the person must perceive the idea as new or innovative and it has to be relevant to their context.

Conversation is now dead in the age of social media chats and messages. Also, there is an “infodemic” — we are inundated with unverified news about the pandemic. In this media-saturated environment, concise and scientifically validated information is getting lost

Parallel to diffusion of ideas is the concept of dissemination of ideas. If diffusion tends to relate to uncontrolled natural spread, dissemination has concerned itself with the conscious efforts to spread new knowledge, ideas, policies, and practices to specific target audiences or to a public at large. Both modalities of diffusion and dissemination of ideas have to be successful in order to produce adoption of new behaviour.

The final piece, to complete the jigsaw puzzle, is implementation. It is recognised, as we are now realising at the expense of unfolding tragedy, that even when information, ideas, or policies do reach intended users, and even if they profess that they accept and intend to use them, the effective application tends to wane and deviate from the intended use. We practised the safety measures to avoid Covid surge for a period of time but lost the plot after some time.

So, what does social sciences and communication theories teach us about more effective communication, which ultimately will lead to implementation of mass behaviour change?

Rise of ‘infodemic’

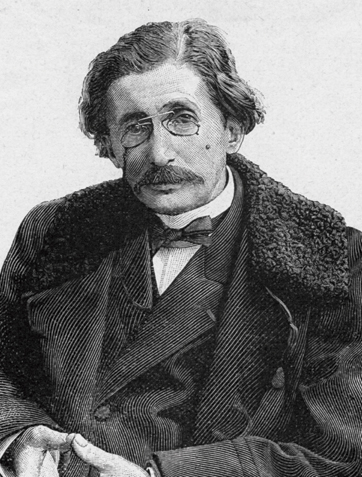

In 1890, Gabriel Tarde, a French sociologist, attributed the basis of social life and advances of society to the desire for imitation inspired by people with original ideas (intellectuals, artists, creators) that spread through human interaction to the less-educated classes (proletarians, farmers). “This original act of imagination and its spread through imitation was the true cause, the sine qua non of progress.”

Gabriel Tarde, French sociologist

Conversation is, as a consequence, the most powerful agent of imitation, of sentiment’s propaganda as well as ideas and forms of action

Gabriel Tarde, French sociologist

conversations as the main channel of influence. “Conversation is, as a consequence, the most powerful agent of imitation, of sentiment’s propaganda as well as ideas and forms of action.”

More than 130 years later, Tarde’s ideas appear justifiably dated. He wrote this before the emergence of widespread literacy and before the development of most of the mass media. “Conversation” is now dead in the age of social media chats and messages. Also, there is an “infodemic” — we are inundated with unverified news about the pandemic. In this media-saturated environment, concise and scientifically validated information is getting lost.

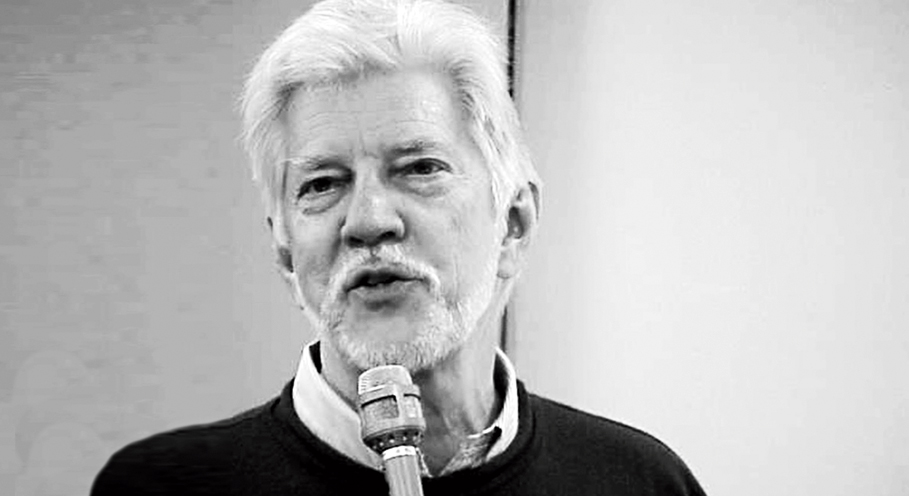

Moving on to more contemporary times, the author Malcolm Gladwell gives some cogent explanation about diffusion and dissemination of ideas, in his bestselling book, The Tipping Point. He offered an interpretation of the process by which a given idea, product, or behaviour could become a part of the mainstream. He used the term ‘tipping point’ to explain how certain phenomena spread out to an entire group or population when a critical mass of people has been reached. Gladwell defines tipping point as “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point”.

Malcolm Gladwell, the author of The Tipping Point, used the term ‘tipping point’ to explain how certain phenomena spread out to an entire group or population when a critical mass of people has been reached. He defines tipping point as “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point”

As with some of the earliest diffusion theorists, Gladwell compared a bestselling product or popular practice with a virus that eventually provokes an epidemic. The irony of his using virus as a metaphor, under these circumstances, is inescapable!

To spread the virus of opinion or practice, beyond a minority of a population, the idea needs to be promoted by at least three types of people — connectors, mavens, and salesmen. All three of these might align roughly with what diffusion theorists call early adopters of ideas.

Connectors are people with good social skills and professional experience in a variety of different fields that make them unique in connecting many diverse people whose lives would not otherwise intersect. Bureaucrats, policy makers and politicians will fall under this category.

Mavens are experts in specific fields (in this situation infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, public health specialists) who like to share their knowledge and to help other people make choices.

Salesmen are people with outstanding personalities and impressive persuasive powers to influence what others buy or accept. We have a plethora of stars whom we love, idolise and devote our attention span to. They fall under this category.

An idea that receives the attention of these three types of people will likely succeed, according to Gladwell. However, he also emphasises the contribution of interpersonal networks. Media-saturated environment have made people more cynical to the messages that is conveyed by the media. Hence, standard public interest messages are increasingly ineffective in sparking trends and creating opinions.

It is under these circumstances that a synergy between interpersonal influence, mass media messages, actions and words of “salespeople” is desperately required to produce longer-term behaviour changes, which are required to keep us safe. I feel that in order to orchestrate a change in our behaviour, we now need multiple skilled musicians playing the music together like an orchestra. Each one has to do their bit, to produce a symphony, which reaches our consciousness and propels us to change. It can only happen if there is a political will to make it happen and as a community we accept the cost of not adopting is simply untenable.

E.M. Rogers’s Diffusion of Innovation theory attempts to explain how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and diffuses (or spreads) through a specific population or social system. We practised the safety measures to avoid Covid surge for a period of time but lost the plot after some time

The research on influencing people to bring about behaviour change highlights the need of synergy at multiple levels. The connectors, mavens and salespersons have to sing from the same hymn sheet. The framework of how to do it exists within the field of communication and social sciences. Evolution and survival, which is at stake now, necessitates adaptation. It is a formidable challenge but hopefully achievable.

Dr Jai Ranjan Ram is a senior consultant psychiatrist and co-founder of Mental Health Foundation (www.mhfkolkata.com). Find him on Facebook @Jai R Ram