"Getting beaten on a story is bad enough, but waiting to get beaten on a story is unbearable."

- Ben Bradlee in A Good Life: Newspapers and other Adventures

From the signature opening bars of CCR's Green River, Steven Spielberg throws us into Vietnam. Copters whirling the skies, barely visible from the swampy terrain of thick forests, you can't even make out if it's night or day. Body bags lined in the foreground, the sound of gunfire working up an eerie rhythm with the pattering of rain. Under a tent is a man typing away furiously. The opening sequence of The Post takes you back to the proxy Cold War that never seemed to end.

The executive editor of The Washington Post, Ben Bradlee's admission comes upfront in Chapter 13 of his memoirs. It is about the agonising days preceding the publication of stories in The New York Times based on the Pentagon Papers, a 47-volume, 7,000-page top secret study of America's military and political involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967 - in short, a record of the lies perpetrated by consecutive governments to fight a war they knew the US could not win.

The Post's meticulous construct is framed around the dramatic events, spanning all of 17 days in June 1971, when NYT is restrained from publishing further reports on the Pentagon Papers; The Washington Post was till then eating humble pie by publishing rewrites of the NYT expose, managing to get 4,000 haphazardly arranged pages of the papers and then trying to put together credible stories for the next day's edition within six hours of deadline. Watching over them is Big Brother, a vindictive Nixon administration, turning on the heat by threatening to bring on criminal espionage charges amid a near-revolt of Post journalists when confronted with company lawyers urging restraint. In between, there are frenetic trips to several courts, arguments, sleepless nights preparing depositions in defence of the freedom of the Press against the government's national security argument and finally, the Supreme Court ruling, six-to-three, in favour of the newspapers' right to publish.

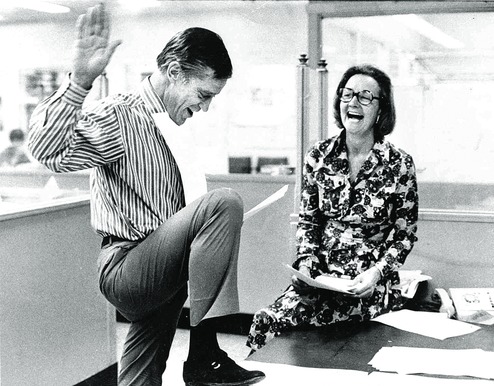

Yet at the heart and soul of these quick paced sequences, captured eloquently in wide angled shots of soothing blue-grey hue by cinematographer Janusz Kaminsky, is the coming of age of Katharine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post, a happy and content homemaker and mother of four, who was thrust into the job after the suicide of her husband, the legendary Phil Graham. It falls on her to take the final call, a decision on which will hinge the very existence of the paper, that, to compound matters, was in the throes of going public, not to mention the sundry television and radio stations they owned.

We all know what she ultimately does. True grit if there ever was, she was it. Yet, what was it that made her say yes? It all boiled down to the understanding that the Post was in the job of doing the "public's business", as she writes in her expansive, Pulitzer Prize winning memoir, Personal History.

"...the material in the Pentagon Papers was just the kind of information the public needed in order to form its opinions and its choices more wisely. In short, we believed the papers were so useful to a greater understanding of the way in which America became involved in the Vietnam War that we regarded their publication not as a breach of the national security, as the administration claimed, but, rather, as a contribution to the national interest - indeed, as the obligation of a responsible newspaper."

Not losing sight of a newspaper's mission is perhaps easier for an editor. But for a proprietor, with one eye on revenue and profits, the economic realities that keep a journalist enterprise running, it is way more complex. Bradlee, therefore, knew from start that publication of the Pentagon Papers was the one shot the Post had to be catapulted into the ranks of the mighty NYT. "Failure to publish without a fight would constitute an abdication that would brand the Post forever, as an administration tool of whatever administration was in power," he wrote in his memoir.

So, was there a clincher at inflexion point? There was, in the form of Edward Bennet William, a lawyer whom both Graham and Bradlee describe as one of the best and most respected. A friend of Bradlee's, William is not featured in the movie. But, it was he the editor turned to. Interrupting the divorce hearing of the then president of McDonald's being held in Chicago, Bradlee got to talk to him on the phone, even as the lawyers and journalists argued at his Washington home that had been turned into a temporary newsroom. Bradlee gave a 10-minute lowdown on the crisis at hand and waited for what he remembered as 60 seconds of deathly silence on the other end.

Then William spoke: "Well, Benjy, you got to go with it. You got no choice. That's your business."

Bradlee narrated this conversation to everyone, including Graham. The utterance of the word "business", held the key. It is the government's "business" to withhold. It is the free media's "business" to publish. "That's what newspapers do: they learn, they report, they verify, they write, and they publish," Bradlee would write later revisiting those tumultuous times.

That would not be the last time a newspaper would act as it is meant to. Immediately after the Post's publication of the story - steaming off its hot metal printing press - many others like the Chicago Tribune and The Boston Globe did so too in solidarity. In India, we know how several newspapers stood up to censorship of the media during the Emergency. Many of them still hit the stands, trying every day to not lose sight of that shining legacy.

It's chilling to hear President Nixon talking about keeping out the Post's reporters and photographers from the White House in the aftermath. Not because the movie uses original recordings - Nixon had all White House phone conversations taped, remember - but because it is so today. Authoritarian leaders the world over will continue to think the same way and make it their "business" to muzzle the media. And newspapers must find the way to raise their voice and be heard.

Before the roll of The Post's end credits, we see a dark corridor lit up only by a security man's flashlight, and a door bolt masked with white tape so that it doesn't close.

The shadowy scene is tightly framed, Spielberg's doff to cinematographer Gordon "Prince of Darkness" Willis of All The President's Men. A burglary is in progress at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, a reminder that Watergate is about to unravel.

Within the cosy confines of the plex screening The Post that Sunday evening, the audience clapped gently, as if overawed by the stirring homage to purposeful journalism that it had just witnessed. I admit I was. Of the 50 journalist friends I messaged that night, one seasoned veteran said she was already at a screening, confessing hours later how she did feel happy and proud of her chosen profession.

A story about events in 1971, oddly about a paper that did not scoop, but followed up, on a rival's story, The Post is a call to arms to journalists the world over in year 2018. The Washington Post is no longer with the Graham family. Yet, its story is a reminder to us about the job we do.

Ask the question. Find the answer. Write the truth.