Bidaay Byomkesh. Adieu, Byomkesh! Byomkesh is no more. Then what is it that keeps returning? His ghost? One of the things that Bidaay Byomkesh, the latest film on the famous Bengali fictional detective, Byomkesh Bakshi, is likely to be remembered for is the camp, tall, "effeminate" policeman who, at some point, bursts on the scene dressed in drag. Some shots before that, Byomkesh's grandson, and the hero of the film, gratuitously informs the audience that the policeman is "gay".

Truly mystifying things follow. The plot, slow and meandering has a powerful, soporific effect on viewers, and its absolute incomprehensibility does them in. From the edge of their seats, viewers recede into the depths of their chairs, and some gently snore even as Byomkesh remains ensconced mostly in his pretty home.

The audience is not even told clearly what it is that three generations of Bakshi males - the aged Byomkesh, his son Abhimanyu and his researcher-grandson Satyaki - are all staking their lives for. What is the problem? Not being told this, as far as the convention of detective stories goes, is an unpardonable crime. Ambiguity is fine in characters, but the plot should be intelligent.

The audience leaves with the message that in some complicated way, sexual deviance is related to moral deviance. Such information is out of place anywhere now, but more so in a Byomkesh Bakshi story.

True, Bidaay Byomkesh is an extrapolation. Directed by Debaloy Bhattacharya, the film is only based on the idea of Saradindu Bandyopadhyay's detective whose first stories are set in the 1920s. (Can we expect a prequel soon?)

Bidaay Byomkesh places the detective, who calls himself "satyanveshi" (the seeker of truth, and not "detective" or " goyenda", the Bengali for detective), in contemporary Calcutta. The city, now "global" in its outlook and technology, can challenge Byomkesh, but of course the light of pure reason emanating from him will dispel all darkness.

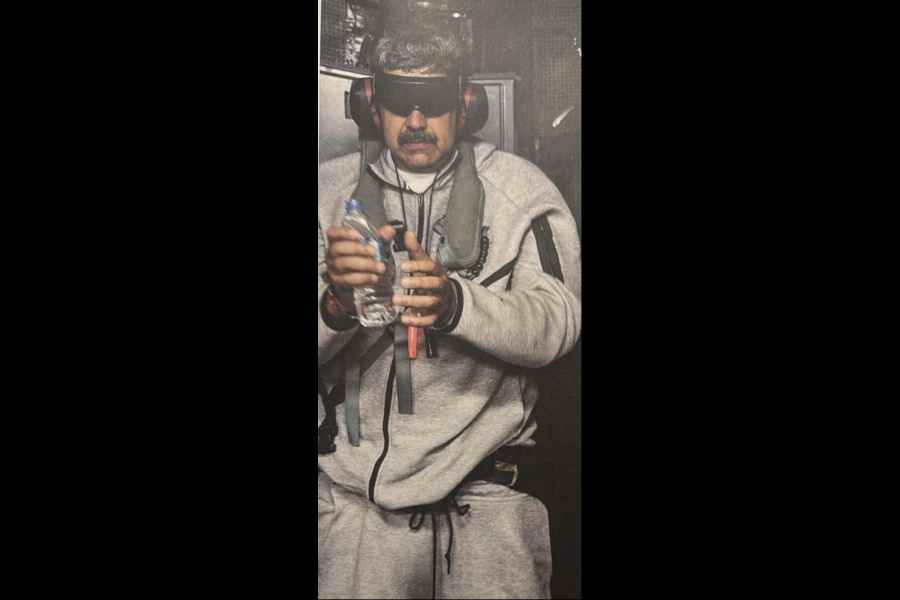

The light has been emanating a lot of late. According to one list, Bidaay Byomkesh is the 13th Byomkesh film in Bengali to be released since 2009. Abir Chatterjee - the veteran of six Byomkesh films so far and the most popular actor currently to play the detective - is Byomkesh in this film as well. Chatterjee also plays Satyaki, Byomkesh's grandson, who looks set to take over Byomkesh's legacy. Another Byomkesh flick featuring him will be released this year.

Bidaay Byomkesh does not mean what it says. Byomkesh is dead, long live Byomkesh.

So what makes Byomkesh tick on screen? One obvious reason is the success of the films. Success begets success in popular culture, reminds Mainak Biswas, who teaches Film Studies at Jadavpur University. But there are other reasons too.

Saradindu, popular novelist, short story writer and screenplay writer for Hindi and Bengali films, wrote his 32 Byomkesh stories between the 1920s and 1970. Scholar Sukumar Sen, in his introduction to the edition of Byomkesh stories brought out by Ananda Publishers, writes that Satyanveshi, the story that introduces Byomkesh and Ajit, his friend, assistant and amanuensis, is set in 1924. (It inspired the 2015 film, Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! directed by Dibakar Banerjee.) The 33rd Byomkesh story Saradindu started to write in 1970 was Bishupal Badh, but he died the same year, before he could finish it.

The timeline of the stories, from "the pre-independent to the post-independent" decades, ensures a kind of Bangaliyana or Bengaliness that directly feeds into Bengal's nostalgia industry, says Biswas.

Bangaliyana can be interpreted as a certain kind of traditional behaviour, lifestyle and culture attributed to Bengalis of yore, rooted more in a romantic idea of the past than in history, and being manufactured wholesale by the market and the media, including contemporary Bengali films. Exactly the impression that you retain from Bidaay Byomkesh.

Many Bengali films now are pegged on this past. "If we have nothing to look forward to, we have to look back," says Biswas. "The films become a matter of period reconstruction and Byomkesh's films are no different," he adds. Into this vision of the past, a figure like Byomkesh's injects thrill and adventure. In fact, more.

Byomkesh is a detective in the classical mould, one of the earliest successful independent detectives in Bengali fiction - the first one, says Sen, was Debendrabijoy Mitra by Panchkari Dey. Byomkesh is a romantic figure, though not exactly because he is married to Satyabati, who, now often played by Sohini Sarkar, appears much more extensively in the films than in the books.

A detective identifies the criminal and restores his environment to its moral order. Detective fiction, in that sense, is a version of the pastoral, in which the audience can assume that the world in its natural state is innocent. This is one reassurance audiences need now more than any other, and certainly in Bengal.

Detective fiction is essentially escapist, reminds Sajni Mukherji, former professor of English at Jadavpur University. Recently other detectives have performed well on the Bengali screen as well. Some, presumed dead, have even been resuscitated. Satyajit Ray's Feluda, Nihar Ranjan Gupta's Kiriti Roy, Sunil Gangopadhyay's Kakababu, Samaresh Basu's child sleuth Gogol, Syed Mustafa Siraj's Colonel Nilratan Sarkar and Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay's Shabor Dasgupta have all made their appearances.

Abir Chatterjee speaks with great enthusiasm about the most famous character he has played. He points at the detective's moral agency. "Saradindu never lost his fan following and Byomkesh remains a superhero off-screen too. He is that rare person with a spine," he says.

However, he also admits the unfailing power of Bangaliyana. "We have not much to be proud of now and Bangaliyana has its own charm, to which Byomkesh films lend themselves," the actor adds.

Even within the ambit of Bangaliyana, Byomkesh has a few advantages over the other Bengali sleuths. Unlike Feluda, he has a more developed inner life and allows his life to be shaped by his social and political contexts.

The story Adim Ripu (Primal Instinct), set in 1946, for example, starts with Byomkesh and Ajit in their Harrison Road home talking about the Hindu-Muslim riots and related familial concerns. Adim Ripu inspired the first film Chatterjee acted in. Titled Byomkesh Bakshi, the 2010 film was directed by Anjan Dutta.

Byomkesh was modelled on Saradindu himself, a tall, handsome man with a shining wit, says journalist Partha Chattopadhyay. Unlike other tall and handsome detectives, Byomkesh is married. The marital bliss he shares with Satyabati is considered to throb with great cinematic potential and has already led to an uninhibited display of poetry, romance and domestic harmony. The other reason for the current Byomkesh wave has to do with the fact that the copyright to Byomkesh stories is available more easily compared to some other detective tales.

But Byomkesh was always a screen hero. In the 1990s, Basu Chatterjee directed a Hindi TV series for Doordarshan, which many consider the best Byomkesh on screen to date. In 1967, Satyajit Ray directed Chiriakhana, with Uttam Kumar as Byomkesh, in which the detective's character was tweaked to make him quite unrecognisable. Perhaps the urge to redo the super-sleuth is an adim ripu, primal instinct? The same thing is being done with Sherlock Holmes, the greatest name in the pantheon.

Holmes, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, has been famously reinvented by BBC in its new series. "It is an attempt to contemporise Holmes subtly," says Mukherji. The first episode, titled A Study in Pink, is a shade significantly different from the original story, A Study in Scarlet, and takes care of a few things. "Set in current-day London, the episode is fast-paced, but that does not mean relationships are not discussed in detail. In half an hour, certain issues are raised and settled - Holmes is not gay, Watson is definitely heterosexual, and certain black people are influential in contemporary London," explains Mukherji.

In other words, the series shimmers with markers of "correct", contemporary identities, but the pleasure of viewing it may not be the same as that of watching the earlier BBC series featuring Jeremy Brett, says Mukherji.

But if Holmes is being opened out, the millennial Byomkesh is going the other way: nostalgia-nourished and homebound, he is being closed in. The films often become just a reiteration of an aesthetic, of a setting. The real problem is forgotten, we are lost in distractions. The nuances of the original, charming stories go missing, says Mukherji. Or even chunks of history.

Dibakar Banerjee's Hindi film, Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! for example, tries to be a noir flick set in 1943. It has a gorgeous Sushant Singh Rajput romping through the dark, seductively shimmering back streets of a pre-World War II Calcutta, even as deadly forces from different parts of the world converge and sexy sirens sizzle and breathe their last.

But, as a critic asks, if the film is set in 1943 Calcutta, with history playing an important role, how can the film be shot without a reference to the Famine that killed about three million people?

Recreating the past is not easy. Interrogating it is even more difficult. But building a set with antique furniture is not hard. Or building an exotic locale. In Har Har Byomkesh, an adaptation of Banhi Patanga, a story of illicit love, among other things, the locale is shifted from Patna to Banaras, which would be more picturesque anyway.

The film, directed by Arindam Sil, features Chatterjee as Byomkesh. Here too, much more than the drama and the playing out of the proclivities of the human mind, the film focuses on the lush interiors of a well-lit mansion. And the final chase - Byomkesh was not given to much action - is conducted to rousing Shiva chants, adding to the detective's character a religious dimension hitherto unknown. Rituparno Ghosh's film, Satyanveshi, based on Chorabali and featuring director Sujoy Ghosh as Byomkesh, also excels in pretty interiors.

Of course, Bengali films seriously lack in new ideas. But to only reconstruct a past as merely Bangaliyana when the hero is Byomkesh, is to also avoid looking at what is happening inside the mind.

Byomkesh may not be dead, but he is not alive either. His uneasy spirit is watching over us.

Something is rotten in the state of Bengal.