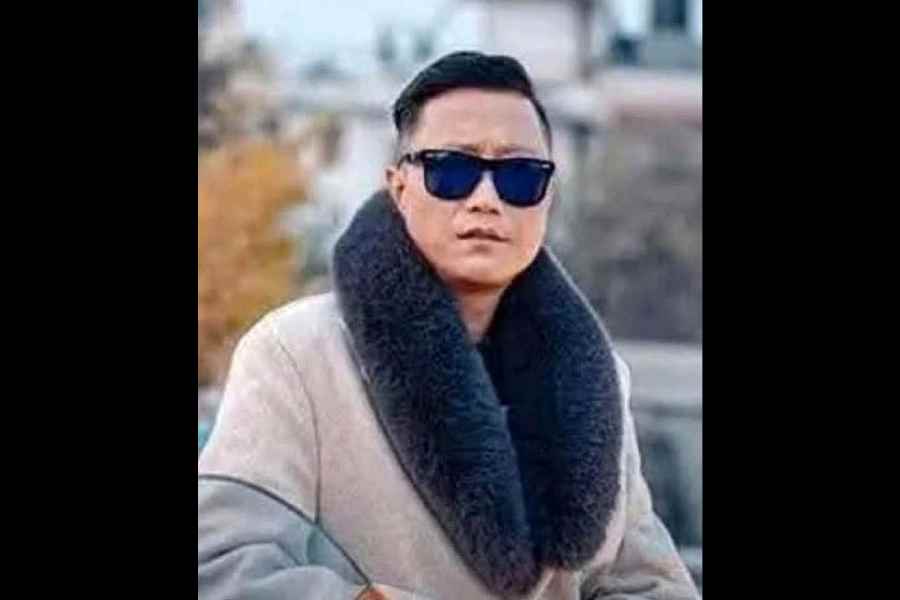

Author, occasional blogger, one-time professor, mother of two and grandmother of three — Neelima Dalmia Adhar has many identities. The writer of the memoir Father Dearest: The Life and Times of R.K. Dalmia, the novel Merchants of Death and the more recent The Secret Diary of Kasturba, a fictionalised biography of the wife of Mahatma Gandhi, Neelima spoke before a select audience at An Author’s Afternoon — presented by Shree Cement and Taj Bengal, in association with t2, Prabha Khaitan Foundation and literary agency Siyahi at the star hotel in Alipore — in conversation with communications professional Supriya Newar. Excerpts....

Mother dearest

My mother, Dinesh Nandini Dalmia, was a Hindi writer who was awarded the Padma Bhushan posthumously in 2006 and had published over 40 books in poetry and prose. She started writing at the age of 12 and was the first female graduate of Rajasthan. She was given the title ‘Rajasthan ki Mira’ because most of her writings were romantic odes in the voice of Mira to Krishna. I often had to edit her work. She had this awful scrawl and nobody could read it. I think, partly it was that which filtered into me and made me the writer that I was to be. My mother was alive when my first book was being written and gave me a lot of insight into my father’s life, into things that happened much before I was born. But I have to admit that after I wrote the book, she asked, ‘Do you really want all of that to go?’ and I said, ‘Too late now, Mom. Ab toh likh diya, ab aisey hi jayega!’ I think she was a little unhappy about some of the parts in the book, especially the candid parts about her. But I think she forgave me.

MOHANDAS, THE HUSBAND

To be able to write about Kasturba Gandhi and to write it in her voice, like a diary rather than a linear narrative from womb to tomb, I wanted to get into the folds of the trauma, the conflict she had in her mind, to be able to deal with the ordinariness of the extraordinary man that she married. She was living with Mohandas, she wasn’t living with the Mahatma. In all such iconic figures’ lives, the first casualties of that ordinariness are the wife and children. So I lived Kasturba, I spoke her voice, I lived Harilal, I emoted with him very deeply. I often used to read out excerpts of my book to my children, my son and my daughter, and my son said, ‘You could well have titled this book ‘Mother Dearest’.’ I’d go as far as to say Gandhi would not have been ‘Mahatma’ had it not been for Kasturba. She is not the image that Richard Attenborough had painted, of the blink-and-miss Kasturba clad in a khadi sari who is a puppet. She was vocal, passionate, self-confident and fearless.

It wasn’t difficult to write her thoughts but I would be lying if I said that I wasn’t brutalised by the story. To write about Gandhi, the cruel father and tyrannical husband that he was, was like reliving a life that I had buried.

Two incidents which I’ll carry with me to my grave are when one of my followers on Twitter sent me a message saying: ‘I read your book and I would like to see a day when, instead of Bapu, we will have ‘Ba’ on the currency note!” And at the Delhi launch, Shashi Tharoor was releasing the book and we were having a heated discussion about Gandhi’s sex life and he was very diplomatic, he summed it up by saying, ‘So, in one word, we should say that Neelima has given Gandhi an ‘Adhar’ card!’

NEELIMA, THE WRITER

I’m a writer, partly by default and partly by legacy, from my mother. The book on my father was more of a journey into myself. The second one was a work of fiction based on a lot of material I had gathered while I was researching my father’s story. I was born when my father was 58 years old and I was the fourth child of his sixth wife. We were 18 siblings. When I started writing, it just flowed out, unchecked. I call it an exorcism. I was able to deal with and remove phantoms from inside of me, which I didn’t even know existed.

My discipline of writing was different for all three books. I wrote the first book in nine months. When I put my pen down for the first time, I had written one-third of the book. Maybe it was some other energy writing in me, maybe my father, maybe some stepmother!

The third book was my most difficult book, because firstly there was lack of information on Kasturba. So I researched for two years, wrote about 30,000 words and then I put the book away. I was absolutely exhausted and burnt out.

I said, ‘God doesn’t want me to write this book, somebody else will write it.’ And surprisingly, I picked up the book again and it started flowing. I kept that discipline, I wrote 500 words a day and I finished it in a year. I was writing sometimes for as many as 18 hours a day. I wasn’t seeing my friends too much and a friend sent me a note asking, ‘Can we meet Neeliba?’

Writing is my soul. I think it was destiny and I would have been very sorry if this had not happened.

MOM & GRANDMOM

I have to say that the core personality that I very preciously guard is being a mother and a grandmother. My children are my best friends, my best critics, the filters to who I am today, the way I dress and the way I talk. I give them total credit for who I am. My children have shaped me more than my parents. And I am surrounded by youngsters. I think that’s the reason why I can claim to be young. My granddaughter says, ‘Nani, Mom never likes to go out with you because everyone thinks you are the masi!’

18 SIBLINGS, 4 STEPMOMS

The ordinary and the saintly are of no interest to me. It’s the wicked and the bizarre — that is what attracts me. I’m not saying I’m the best judge of it but I’m definitely drawn to it. I think part of that I can blame on my life because I had a bizarre childhood. I don’t remember anybody in my peer group or around me in society who had a home quite like mine, in which there were four stepmothers and 18 siblings and a father who went to jail when I was in Class VIII!

FUTURE PROJECTS

For the moment, I’m still consumed by the success of The Secret Diary of Kasturba. The womb is still vacant because I had set myself such a high benchmark. I am not a programmed writer. Something has to grip me, and so hard by the throat that I can’t breathe unless I set it down on paper. Birth and death fascinate me. I have a huge foetal fixation and one of the reasons for that is that I was in my mother’s womb for 11 months. I was born at home as they didn’t want to go to a hospital. Death is something that I have watched very closely. It fascinates me, I fear it and I romance it. I have often thought of writing a book in the voice of death. I’d play death, the narrator.

Text: Rushati Mukherjee

Pictures: Arnab Mondal