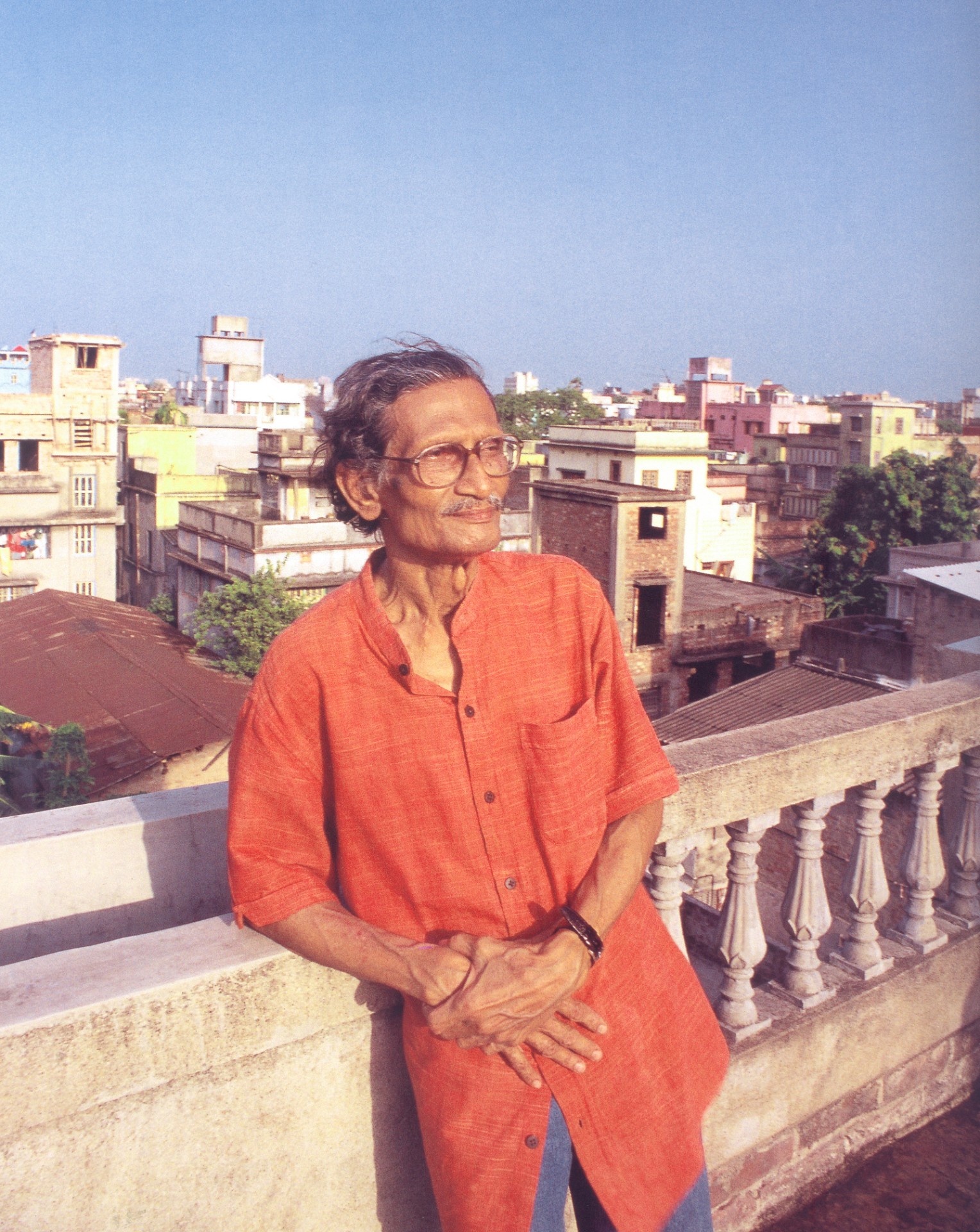

Ramkinkar Baij (1906–80) was the vanguard of modern Indian sculpture along with Sankho Chaudhuri, D.P. Roy Chowdhury and Prodosh Das Gupta. Known for his larger-than-life outdoor concrete statues, Baij broke the shackles of British studio sculpturing taught in the Anglicised curriculum of colonial art colleges. He worked in concrete, a more viable option than the expensive and rare plaster of Paris, which he combined with laterite pebbles from the Khoai (a geological formation native to West Bengal)—an act that rooted his art in and around Santiniketan. These sculptures emulated the artist’s zeal for life and nature.

In the 1950s, the Reserve Bank of India commissioned Baij to make dvarpala (protective figures placed outside the doors of temples) sculptures for its New Delhi offices. For the Yaksha and Yakshi sculptures, he had stone brought specially from Baijnath in Himachal Pradesh at a great cost. Even though the project was delayed, the two pieces showcase Baij’s quality at the national level—the Yaksha holds a pinion and a bag of money, while the Yakshi stands with flowers, agriculture produce and a rudder in her hands.

Grounded and Abstract

Baij’s outdoor sculptures rise out of the ground, much like the termite mounds seen growing out of the red soil of Birbhum. His chosen medium, cement—which could survive the extreme heat and monsoons of Bengal—was difficult to handle. Unlike wax or clay, it hardened quickly and could not be smoothed out. He built each sculpture around metal armatures, applying the paste in clumps and then chiselling away the excess. The result was a uniquely textured surface on his voluptuous figures. Sujata (1935), modelled after fellow artist Jaya Appasamy, is the earliest sculpture he made with cement. Among such works, Santhal Family (1938) and Mill Call (1956) stand out as iconic sculptures, made as a celebration of the working class and the Santhals. Another outdoor work, Lamp Stand (1940) is arguably the earliest abstract sculpture by an Indian artist.

In addition to these large works, abstraction is also imbued in the busts he made. Instead of merely transcribing the physiognomy of facial features, each bust tries to emulate the essence of his sitters. However, this abstraction was cause for scandal, especially within the political community. In 1984, a minister from West Bengal threatened to have a bust of Rabindranath Tagore removed from the town of Balatonfured in Hungary. The statue was later replaced with a different variant, while the original was moved to Room 220 of the State Hospital for Cardiology, where Tagore had received treatment in 1926. Similarly, in 2017, Siddhartha Bhattacharya, a political leader from Guwahati, raised allegations about a Mahatma Gandhi sculpture on the grounds that it did not resemble Gandhi.

Baij seldom paid heed to such detractions, choosing to showcase the prana or life force of his subject rather than a mere representation. His first image of Rabindranath Tagore, The Poet (1937), is one such example. Both symbolist and post-cubist in execution, the face is distorted but still resembles the noble laureate — a narrow head with a profoundly elongated nose, a moustache, a beard that pleats beyond the chin and receding hair that curls inward. Seeing this work upon its completion, Nandalal Bose commented that it resembled a star that should be viewed from a height. A bronze cast of the sculpture forms part of the collection of the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

A watercolour drawing in Baij's expressionistic style Picture source: DAG via Sahapedia.org

Shatadeep Maitra works at DAG, New Delhi. He has worked on major shows including India’s French Connection, M.V. Dhurandhar: The Romantic Realist and as coordinator for the Drishyakala Red Fort museum. This article is part of Saha Sutra on sahapedia.org, an open online resource on the arts, cultures and heritage of India

Yaksha and Yakshini outside the Reserve Bank of India's New Delhi office Picture source: rbi.org.in

Dabbling in paint

In addition to sculpture, Baij was a self-taught draughtsman. Initially, he experimented with the watercolour wash technique taught by Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose. His friendship with fellow artist Benode Behari Mukherjee was crucial in his shift towards expressionism. Mukherjee had attended lectures by Austrian art critic Stella Kramrisch before Baij joined the institution, and passed the knowledge about Western practices to his friend.

Like his sculpting process, Baij painted quickly—ignoring perspective and depth for foreshortening and fluidic patches of colour, where each shape was defined by outlines in dark paint. In works reminiscent of a post-cubist or synthetic cubist style, individual elements of the landscape seem to coalesce into a singular motif. Baij’s oil canvases, undertaken only in the late-1930s, are peppered with texturing similar to the surface of his concrete sculptures.

Unlike artists living in the limelight, Baij was comfortable with his life in interior Bengal. Born to a family of barbers in Bankura, he grew up admiring the region’s folk and popular art. His modernism grew from the celebration of the lives around him and the cultural heritage of the region. Most of us know the man only through his works, and identify Baij as a maverick who upended the norms of sculpturing in India. But for those who lived around him, the man they lovingly called Kinkarda was an occasionally erratic man who loved his cats.