After preparing the Partition formula, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of the Raj, requested Mahatama Gandhi for a meeting. Mountbatten told me when I met him, that he felt there was a halo when the Mahatama walked into the room. Gandhi walked out of the meeting when he heard the word ‘Partition’. Mountbatten then called Jinnah. ‘Your Pakistan is a reality,’ Mountbatten said. He once again tried for some kind of link, however weak, between the two countries. Jinnah once again rejected the suggestion. The rest is history.

***

Jinnah never himself gave up his links with India. He wanted to visit India on a regular basis even after Partition. When Prime Minister Nehru wrote to him and asked what should be done with his two salubrious properties, one in Delhi’s prestigious Aurangzeb Road and the other in Bombay’s equally prestigious Malabar Hill, Jinnah responded by saying he proposed living in India for periods of time every year. There was no question of confiscating ‘enemy’ property.

There is one other example that was cited to me by Jinnah’s long-serving private secretary, Khurshid Ahmed. This was around 1948 and Khurshid was sitting at the dining table of the Governor General’s house in Karachi. Jinnah’s sister, Fatima, was also at the table. A young ADC from the Pakistan Navy, whose own family members were apparently killed during the migration, had the courage to pose the question to Jinnah: ‘Quaid-e-Azam, was Pakistan a good thing to have?’ The old man did not speak for at least a minute, which Khurshid said actually felt like an hour. Then he said, ‘Young man, l do not know. Posterity will judge.’

Jinnah was probably less forgiving to himself in private. Khurshid also recounted, how, a few days after Partition and before he left for Karachi, Jinnah responded when he was told of the many massacres (it is estimated that more than one million were killed on both sides). Jinnah’s stunned reaction was summed up in one sentence. ‘They are trying to destroy my Pakistan.’ He had never anticipated, nor could he believe that killings had taken place on such a vast scale.

Mian Iftikharuddin, a rich man who spent all his life in the Congress but then switched to the Muslim League, tells another story of the deeply affected Jinnah who was flown over the region in a Dakota to see for himself the vast migrations that were underway. According to Iftikharuddin, Jinnah put his head in his hands and whispered, ‘What have I done?’ The source for this story was Tahira, daughter of Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, former prime minister of undivided Punjab.

Our own family ordeal was no different from the migration Jinnah viewed from his Dakota. In Sialkot my father summoned the family at our lunch table and announced that he himself was staying back in the newly created state of Pakistan. My elder brother, Rajinder, replied that Muslims would not allow non-Muslims to stay behind. He said he himself had a taste of Pakistan when he was in the medical college at Amritsar. At that time our two communities were evenly divided in the city and the Muslims, who anticipated Amritsar being allocated to Pakistan, would knock on doors to tell non-Muslims to vacate peacefully.

A respectable Muslim family from nearby Jalandhar approached my father, asking him to take their house in exchange for our home in Sialkot. My father repeated to them that there was no question of an exchange, since he was staying back in his home city. Neither he nor they could anticipate that such a peaceful city as Sialkot would witness the forced migration that followed. Sialkot was a good distance from the Grand Trunk road on which so many migrants travelled between the two countries. When I left Sialkot, the environment was peaceful. But when I hit the GT road, I was shocked to see thousands of people travelling in both directions. That was when I finally understood that there would be no going back.

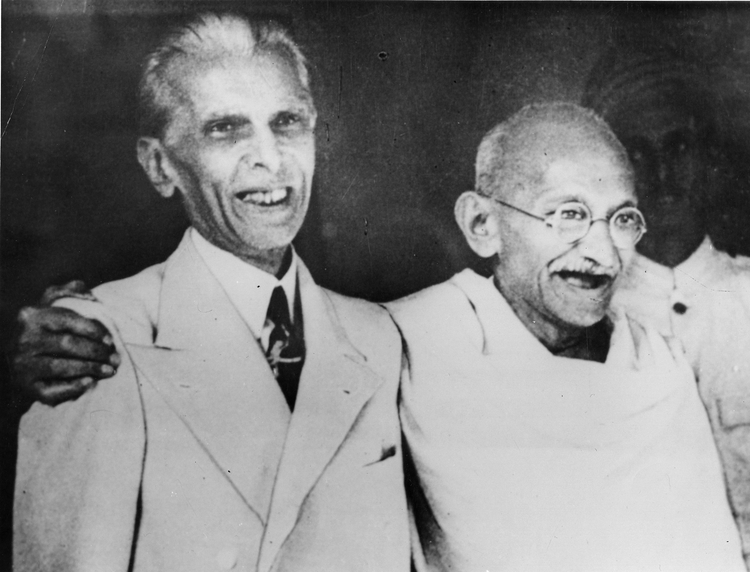

I was in my second year of law college in Lahore when Mohammad Ali Jinnah came to address the students. Habib, my Kashmiri classmate, was an active member of the Muslim League, and had arranged the function. Initially, he did not invite us, the non-Muslim students. But when he realized at the eleventh hour that the anticipated audience would not fill even a classroom, he pleaded with us to come to listen to ‘our Quaid-e-Azam’, the title which Mahatma Gandhi had bestowed on Jinnah. I told Habib that since he had not invited us, we were not planning to attend. Habib was a close friend, so I eventually capitulated and went to listen to Jinnah. The classroom remained partly empty.

This was in 1945, two years before Pakistan was constituted and before the British quit India. Jinnah went over the usual arguments that the Muslims and the Hindus were two separate nations which ate different food, wore different clothes and came from different civilizations. Therefore, the Muslims wanted a separate homeland.

After the lecture, he said he would reply to questions if we had any. I asked him two questions that in retrospect proved to be prophetic. The first was: There was already so much animosity between the Hindus and the Muslims that after the formation of Pakistan on the basis of religion, the two communities would be at each other’s throats. In reply he said that we would be the best of friends. Germany and France fought wars for hundreds of years and yet they now had good relations.

My second question was: What would be the reaction of Pakistan if a third country was to attack India? He said that the Pakistani soldiers would fight shoulder to shoulder with their Indian counterparts against any invaders. ‘Remember, young man, blood is thicker than water,’ Jinnah said.

This was classic Jinnah, asserting one position, only to contradict himself a short time later. His love-hate relationship with India was visible throughout his life. He never forgot that tens of millions of Muslims lived on in India and he felt responsible for the privations they faced.

Years later, when Lal Bahadur Shastri was the home minister and I was serving as his information officer, he confided in me that had the Pakistani troops fought by the side of Indian soldiers and driven out the Dragon during the Indo-China war in 1962, it would have been difficult to say ‘no’ if Pakistan had asked for Kashmir. Would Jinnah have followed a different course of action from General Ayub Khan, Pakistan’s President in 1962? It is difficult to say. If he had, the history of relations between India and Pakistan would have been different, neighbourly and friendly.

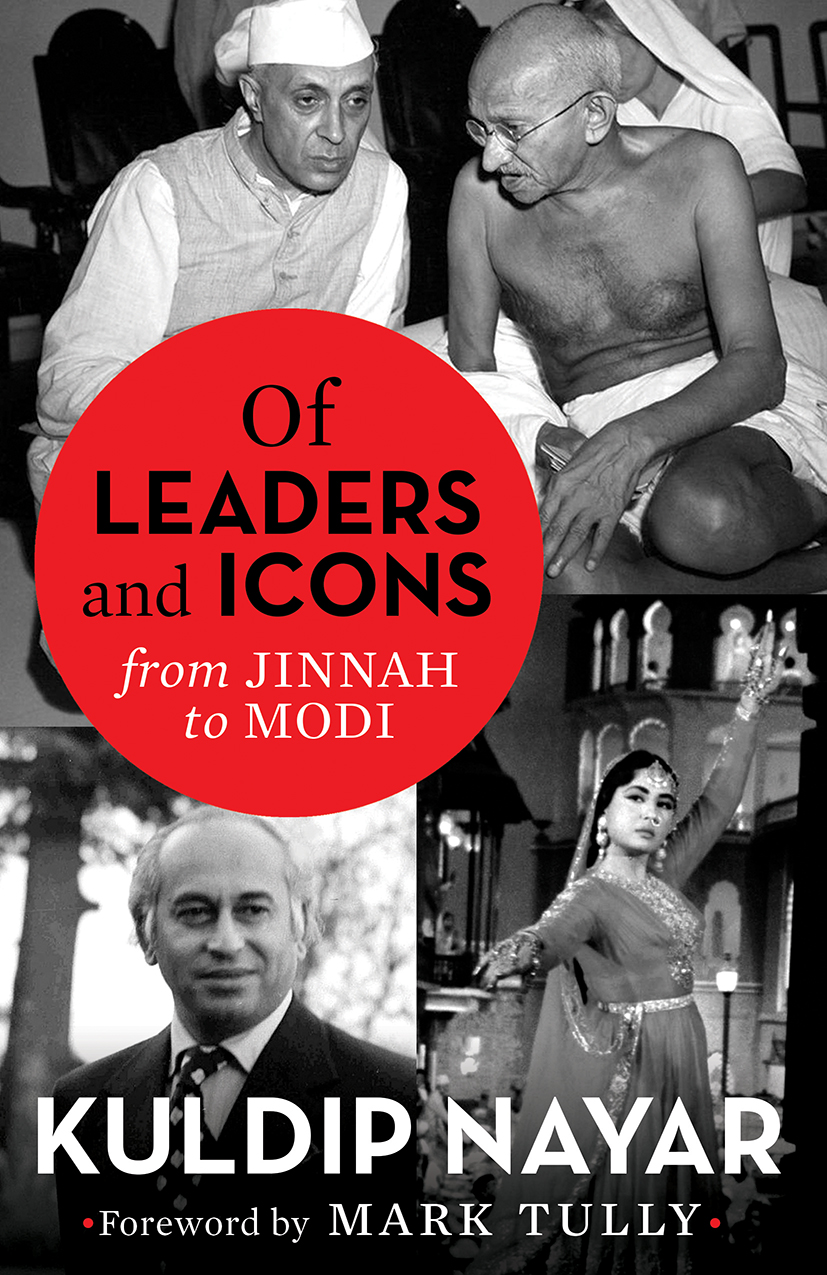

Of Leaders and Icons, from Jinnah to Modi by Kuldip Nayar. Excerpted with permission from Speaking Tiger

Book cover: Of Leaders and Icons, from Jinnah to Modi by Kuldip Nayar Speaking Tiger