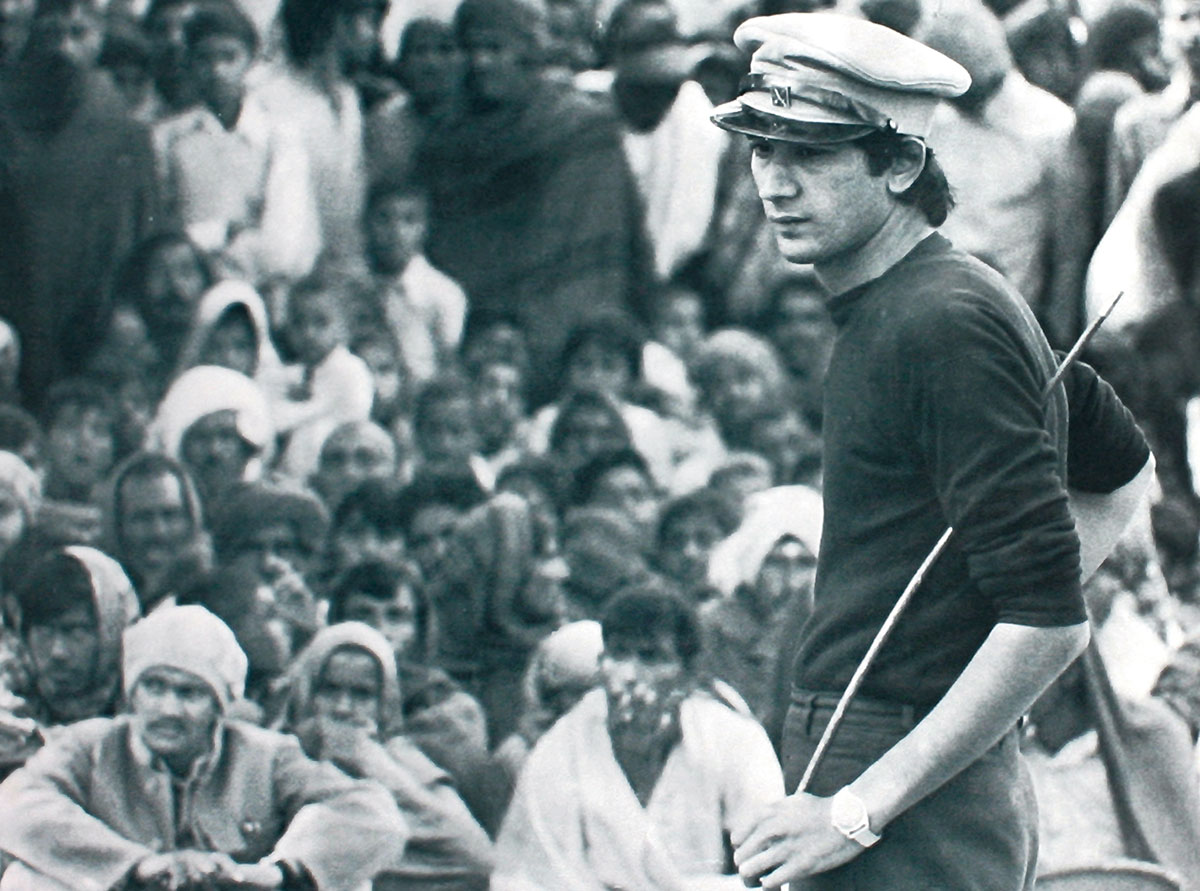

Prasad is right. Not many knew of Hashmi until his death. On January 1, 1989, Hashmi was wounded fatally by a mob led by the Congress’s Mukesh Sharma, when he was staging Halla Bol, a street play about factory workers and their exploitation, at Jhandapur colony in Sahibabad. The play was a solidarity gesture for a Communist friend, Ramanand Jha, who was fighting the Ghaziabad municipal elections. A day later, Hashmi succumbed to his injuries.

Delhi erupted in spontaneous grief. Artistes, filmmakers, common folk, all came together for his funeral. Even the central government was forced to take notice.

Says his wife, Moloyashree, “It was the manner in which he was killed that shook everybody. He was murdered for standing up for the weak. And he was killed while doing his job as an artiste.” Moloyashree was part of the Halla Bol cast on the day of the mob attack, and she went back to Jhandapur two days after her husband’s death and staged the complete play. “We have been holding plays at the same place every year,” she says.

Hashmi worked as an information officer for the West Bengal government when he was in his mid-twenties and his office in Delhi was the hub for creative people from all walks of life, according to his friend and Sufi singer, Madan Gopal Singh. Hashmi was also the founding member of the street theatre group, Janam (short for Jana Natya Manch), which Moloyashree runs now. The group was born following Hashmi’s differences with the Indian People Theatre’s Association or IPTA, of which he was a member.

Some of the better known plays of Janam are Machine, Aurat, and, of course, Halla Bol. Machine highlighted the state of industrial labour and Aurat is about the challenges faced by women in various spheres of life. Though he was a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxists), Hashmi’s friends recall how he transcended the party when it came to theatre. “Even those who were not Communists were part of his group and his main aim was to awaken the common people through thought-provoking performances. That’s what attracted artistes and intelligentsia [to him and his work],” says actor M.K. Raina.

As one of the organisers of the Committee for Communal Harmony at the height of the Khalistan-related disturbances in Punjab, Hashmi took on the menace of majoritarianism too. He also opposed the rise of the Right-wing, which was still finding its feet in the late Eighties.

His brother, Sohail, remembers him as a restless being, “bubbling with ideas”. He would be out on the streets raising awareness about the perils of communalism and the need for peace. Had he lived, many believe, he would have set up an institution for research and study of theatre as a vehicle to transform society.

“Can you tell me about one [other] theatre person who united the artistes and intelligentsia in this country,” asks Sohail. He adds, “Safdar did that after his death and he continues to do it even today.”

Come January 1, Hashmi’s admirers will all be out on the streets of India with his plays, the themes of which remain as relevant as ever. Prasad plans to recite a poem by Hashmi on that day. It is called Bhaichara or Brotherhood. He says, “This is what we need in India today, when communal poison is being injected all across.”

The poem goes thus: “Aaj agar ye desh salamat/Hai toh mere hi bal se,/ Aaj agar mai mar jaaoon toh,/Griha yudh hoga kal se!/Aao, o Bharat desh ke veero,/Aao mujko azad karo.” An evergreen wakeup call. Says Prasad, “We will be doing what he would have been doing.”

People talk of Safdar Hashmi as if he was a man who died at a ripe old age. Posters of Hashmi adorn the tiny Sahmat office in Canning Lane in Lutyens’ Delhi. In his thick glasses, coat-muffler and wide smile, Hashmi looks much older than he actually was at the time the photograph was taken.

On January 2, it will be 30 years since Hashmi was brutally killed. He had turned 34 that year, but had already made a name for himself as a fiery street theatre actor and director. He was also a college lecturer, filmmaker, writer, singer, artist, poet, dancer, Communist activist and an organiser of people. And he excelled in each of these roles. “He became a larger than life figure after his death,” says Rajendra Prasad, a former associate and friend of Hashmi’s. Prasad is currently with the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust or Sahmat; it was founded a month after Hashmi’s murder.

This coming year will not only mark the 30th death anniversary of Hashmi, it will also celebrate 30 years of Sahmat. Over the years, Sahmat has undertaken a variety of activities — performances, exhibitions, publication of books — to underline the idea of unity in diversity of the Indian nation and people.