Book: INDIA’S FIRST RADICALS: YOUNG BENGAL AND THE BRITISH EMPIRE

Author: Rosinka Chaudhuri

Published by: Viking

Price: Rs 899

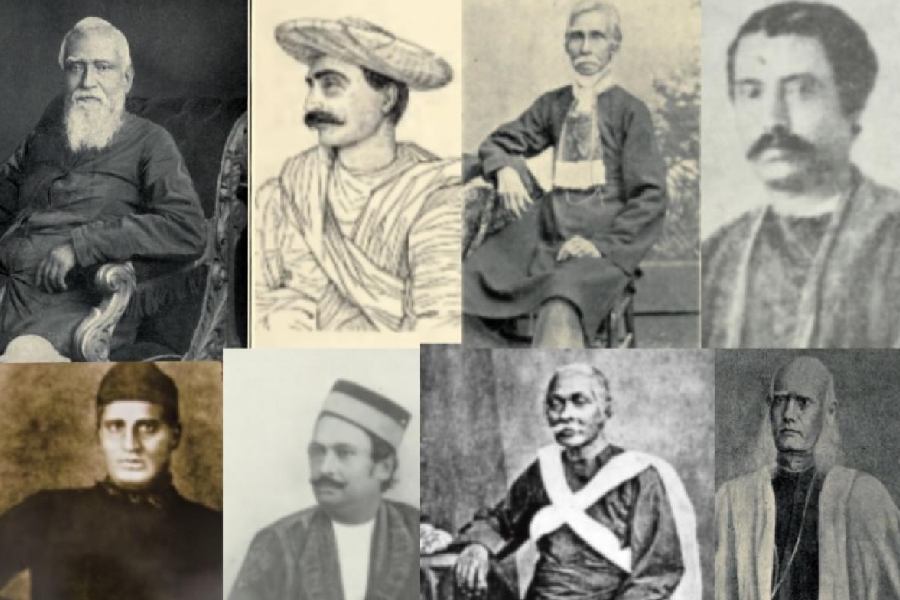

For many of us, ‘Young Bengal’ was a cohort of Hindu College students in the early 19th century under the leadership of their charismatic teacher, Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, who adopted a ‘shock-and-awe’ approach to social and religious reform (involving, infamously, bragging about their fondness for beef to Brahmins). Understandably, they copped a fair bit of criticism for their approach, with the literary scholar, Dineshchandra Sen — prefiguring a tone frequently invoked in today’s India — calling them “anti-national”. Accordingly, many tend to remember the Young Bengal movement as a momentary flashpoint of iconoclastic exuberance in between the more impactful and protracted initiatives of Rammohun and Vidyasagar. That’s why they have not received serious, in-depth scholarly attention up till now. Rosinka Chaudhuri’s book is an insightful, thought-provoking corrective.

For Chaudhuri, the group were “India’s first radicals”, and the “changes they wrought were among the earliest shifts to define modern India as we now know it”. To demonstrate this, she looks not at 1831 — when Derozio was dismissed from his teaching job and his student group dubbed “Radicals” or “the Ultras” in contemporary media — but at 1843, when the group argued for peasant rights, campaigned against judicial and police corruption, sued a British magistrate for mistreating labourers, persisted in challenging racial, gender and caste discriminations, and topped these off by forming India’s first political party.

The group, argues Chaudhuri, thought and spoke in terms — encompassing “equality, inclusivity, the eradication of social and gender discrimination, and a democratic right to freedom of speech” — that were nothing less than the building blocks of the modern life of Indians. Indeed, an 1843 resolution of their party pledged to admit “all persons anxious to promote the good of India”, “without respect of Caste, Creed, Place of Birth, or Rank in Society” — principles that undergirded the ideology of the freedom

movement and the Indian Constitution.

In an influential 1973 article (reprinted in 1985), “The Complexities of Young Bengal”, the historian, Sumit Sarkar, had acknowledged the wide gaps in our knowledge of Young Bengal, its sources being limited to the proceedings of the Society for the Acquisition of General Knowledge, the issues of The Bengal Spectator (edited by Gautam Chattopadhyay and Benoy Ghosh), stray extracts from Enquirer and other notices in India Gazette, The Bengal Hurkaru, and Samachar Darpan quotes published in the Jnananvesana. Sarkar had then conceded that more diligent research was needed to unearth more sources.

Writing half a century later, Chaudhuri keeps alluding to a new archive to open up fresh perspectives — “archival material that has rarely been used”. But this ‘new archive’ turns out to be, substantially, “print material available in detailed press reports and journal summations” in English and Bengali. It’s not very clear if they go beyond the inventory Sarkar had suggested. But that becomes less important when one considers the fundamental difference between their respective approaches. While Sarkar had taken into account the evolving intellectual trajectory of Young Bengal over its lifespan — noting a process of toning down or ‘backsliding’ of political and social radicalism as the group aged and obtained social respectability — Chaudhuri identifies a collective moment in the 1830s and the 1840s that left an indelible imprint on the making of modern India, making any discussion of a subsequent ‘retreat’ secondary.

Sometimes, the book takes a few leaps of faith to buttress the argument about Young Bengal being the harbinger of Indian modernity. Not everyone will be convinced that the act of paying an American bookseller in Calcutta five times the price of Tom Paine’s Rights of Man in 1831, or a shared love for the 1795 hymn to egalitarianism, “A Man’s a Man for A’ That”, by the Scottish poet, Robert Burns, constitutes unimpeachable evidence of a group’s pathbreaking credentials. The assertion that “these were men who, inspired by the radical republican ideals of the French Revolution and the Scottish Enlightenment, attempted to effect change based on a principle of equality”, too, appears a little contrived, at least stylistically.

Yet, Chaudhuri’s most remarkable achievement constitutes establishing that Young Bengal in the 1830s and the 1840s comprised pioneering campaigners in support of peasant rights and was a trailblazer in coming up with the concept of an exploited and oppressed “people of India”. The short-lived party they founded in 1843, the Bengal British India Society, was vociferous in supporting free speech and holding the colonial government squarely accountable for slip-ups and missteps. When one of their own, Radhanath Sikdar, was fined Rs 200 by the British court in 1843 for protesting against a magistrate who had called survey department workers “paharee coolies”, Young Bengal retorted by publishing a detailed account in The Bengal Spectator that unequivocally asserted the “fundamental principles of equality of all British subjects, whether labourers, professional Indians, or white magistrates and collectors.” All told, Chaudhuri pushes back — by several decades and with considerable conviction and analytical rigour — the antiquity of some of the foundational principles that would go on to spawn the ideas of nationalism, citizenship, and modernity.