Book name- 38 LONDRES STREET: ON IMPUNITY, PINOCHET IN ENGLAND AND A NAZI IN PATAGONIA

Author- Philippe Sands

Published by- W&N,

Price- Rs 899

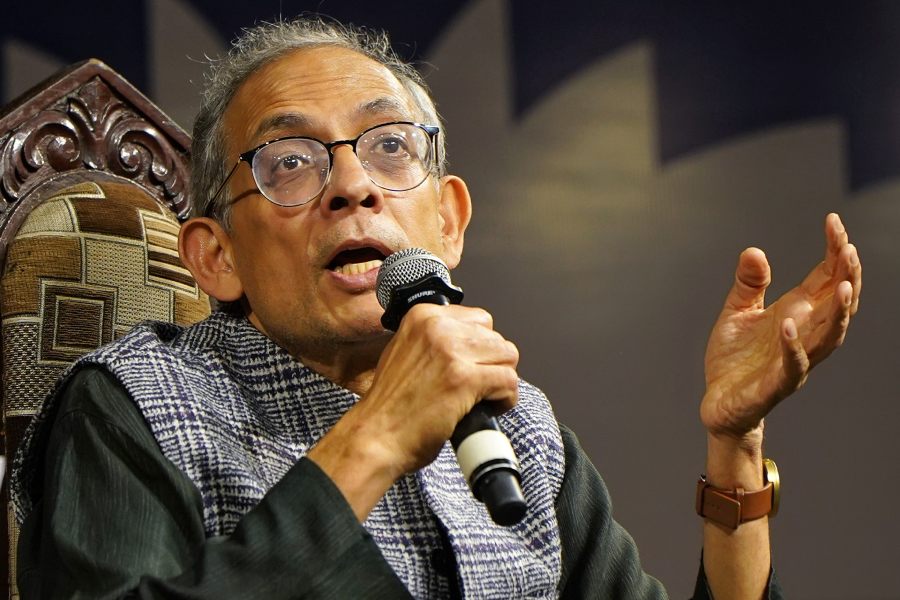

This book captures two parallel stories: the arrest of the Chilean president and military dictator, General Augusto Pinochet (picture), in London in October 1998, and the prolonged legal proceedings to extradite him to Spain to face charges of genocide and torture; the other story is of Walther Rauff, a Nazi war criminal, who had resettled in Chile after the Second World War and successfully resisted attempts to extradite him to Germany.

The Pinochet extradition case is better known. The general had come to power in a coup in 1973, which had overthrown and killed an elected president, the socialist Salvador Allende. As president, Pinochet presided over a military dictatorship notorious for its gross violations of human rights. He retired in 1990 as Chile began a long trek back to a democratic form of government. But in effect, he had immunity from legal processes and charges being brought against him in Chilean courts. He was arrested while holidaying in London in 1998 following an extradition request from a court in Spain for his role in specific acts of torture.

The arrest and the legal proceedings that followed constituted in Philippe Sands’ words “one of the most important international criminal cases since Nuremberg”. The legal principles involved were weighty. The principle of universal jurisdiction had been acquiring recognition internationally. Pinochet’s supporters, however, argued that as a former head of State, he had diplomatic immunity. Pinochet also had defenders in Britain which had greatly valued his support during the Falklands War.

The case of Walther Rauff is equally engrossing. A former German navy officer, he worked his way up the Nazi hierarchy and was closely associated with efforts to liquidate Jewish populations. As the war ended, Rauff was arrested but he managed to escape, first to Syria and then to Ecuador where he also apparently struck up a friendship with Pinochet who was posted there as a Chilean military officer. Rauff finally settled down in Chile — incredibly, he had briefly worked for Israeli intelligence and when in Chile, more regularly for West German intelligence. His past caught up with him in 1963 following a West German request for his extradition for his role in the genocide of Jews. Rauff’s defence was that he was just someone following orders. After 123 days in custody, he was released as Chile’s Supreme Court ruled that on account of a 15-year statute of limitations in its domestic law it had no jurisdiction over acts committed in 1941.

The Pinochet extradition proceedings in London dragged on much longer. In the intervening 500-plus days, the case underwent numerous twists. The final outcome remained inconclusive in that the legal issues of jurisdiction and immunity were never substantively addressed by a judicial verdict.

Pinochet died in December 2006. Although dogged by criminal cases in Chile, he never really faced judicial accountability. Rauff had died in 1984 — without being held accountable for his role in the extermination of Jews in Nazi Germany. Both narratives underline how ‘impunity’ characterised these parallel life stories.

The amount of detail Sands has gathered is staggering and may engulf some readers but the book manages to equitably combine strong moral indignation with a very

clinical telling of two interesting stories wherein accountability failed and impunity prevailed.