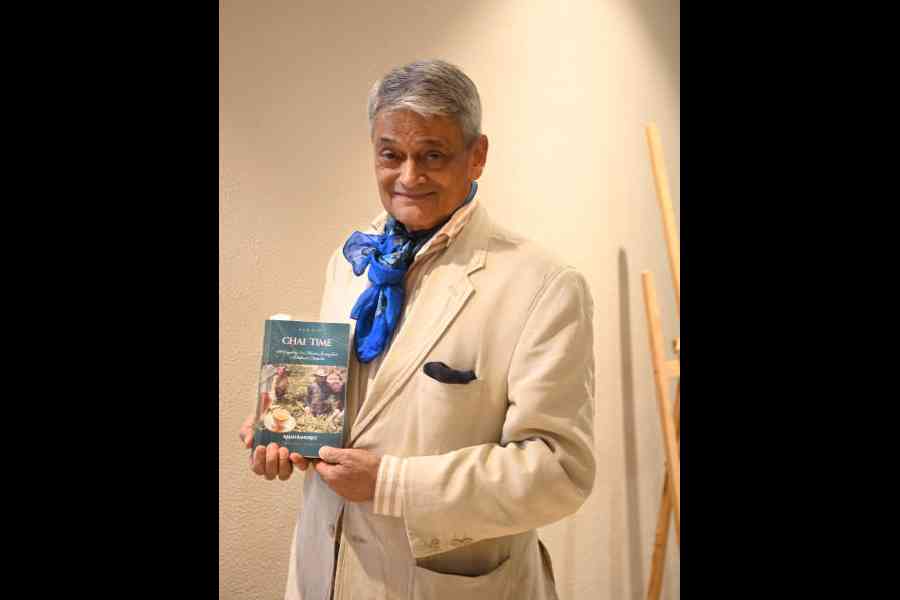

Chai Time isn’t Rajah Banerjee’s first book, but it’s like Darjeeling First Flush — speaks of heritage, unmatched pedigree, has a pleasant note and warms the heart and the soul. Swaraj Kumar Banerjee, who is popularly known as Rajah Banerjee and who is synonymous with organic Darjeeling tea, pours his life in Chai Time: A Darjeeling Tea Planter’s Journey from Makaibari to Rimpocha (Bose Creative Publishers). It’s an excellent chronicle for those who want to know the history of tea estates in Darjeeling right from 1850s under the British, followed by the takeover of political parties and trade unions and the current times. However, Chai Time is still the story of Banerjee, who rose from a fall, who was committed to the land and to its people, who is passionate about the planet and, of course, tea.

Tree planter not a tea planter

“I had a calling when I fell off my horse. No matter how good an equestrian you are — and I’m a pretty good equestrian, I’ve been riding before I could walk — you have to fall. I’ve had many, many falls in my life, some life-threatening, but the one that changed my life was not a life-threatening one; rather, it was revelatory on the soul. When we die, we go to a frequency which is timeless and spaceless, and you can get there either through intense meditation and getting cosmic consciousness, or through what I had experienced,” said Banerjee, talking about his revelatory fall that he describes in the second chapter, Heady Hippie Undergrads, of his memoir. Continuing, he adds: “The trees reached out to me, told me to save them.” He describes the episode of how he convinced his father to permit him to plant trees in the estate. “I’m a tree planter, I’m not a tea planter,” he asserts.

Sustainable score

Banerjee is known for changing the tea cultivation scene by bringing in sustainable practices. “I think we can take full credit for the fact that we pioneered sustainable practices. I don’t like the word organic because biodynamics is 10 times more serious than organic. Sustainability is not an intellectual issue. All sustainable solutions are solutions from the ground up. Because the poorest people, the most marginalised, have to recycle out of necessity. And all I did at Makaibari was look at all my people who are marginalised. So I started with the empowerment of women because women are the most exploited anywhere I’ve been in the world. Women work the hardest, they bend their backs the hardest, and the more marginalised the society, the greater the exploitation,” said Banerjee, who broke the chain of women getting up in the morning to fend for wood in the forest to cook food and introduced them to biogas.

“So, all the mantras and everything that I received are from the gift of the trees. Following what needed to be done, I watched carefully and introduced a non-polluting renewable energy source. She doesn’t have to get up in the morning, she doesn’t have to go through all the ordeal before going to work in the field. My dream is to free all the marginalised people of the world. There are 664,000 villages in India and 180 million (rural) families. That also means there are 180 million women between the age of 45-50 who are homemakers.”

Monopolisation and malpractice

In Chai Time, Banerjee recounts an episode when he discovered a fake Darjeeling tea in a store in Germany. A similar instance came to light recently when a low-quality tea was being sold as Darjeeling tea in India. Responding to the issue, he said: “Humans generally are avaricious. Unfortunately, most of the commerce is with traders and traders only buy cheap, sell dear. That’s a simple philosophy. The German importers did their bit of multiplication; they bought cheap and sold dear. It’s not the English but the Germans who had monopolised the Darjeeling tea trade for over 100 years. They’re good tasters, they’re good buyers, then they’re wholesalers, and retailers, and bankers. So they wear five hats. So, whichever hat is necessary, they put it on. And they have developed this entire mystique around Darjeeling tea. Darjeeling was completely in their grip until we broke it with our internal marketing. You have to break systems to take it to the next level. Then it becomes an open market situation where talent can surface. So that was done. But unfortunately, post-Independence, most of the gardens have been owned by traders, the absentee landlords. They want to make an investment and see where the profit margin is in a very short span of time. Briefly, they jumped on the bandwagon of switching to organics, but not from the heart. People have now gone to Nepal, producing similar types of Darjeeling tea, sometimes even better and you get it at half the price.”

Entrepreneur, activist, et al

Banerjee wears multiple hats. He is a tree planter, an entrepreneur, an environmentalist, a leader and a visionary. Which one does he resonate with most? “I think I’m just a tree planter. The rest have been a gift. They’ve shown me the path to do various things, and I get all my inspiration from trees; I can talk to them. There are so many varieties of herbs, grasses, plants, trees… billions, and they all have one language. While we have only 193 nations and we have 28,000 languages. There’s a community in Italy called Damanhur that communicates with plants. They have their own currency too, which is recognised by the European Union. I’m the Indian distributor for musical plants.”

RimpochA, a new beginning

As our talk progressed, Banerjee, in a heavy tone, mentioned the fateful day when his ancestral home burned down in two hours on March 17, 2017. “I became a celebrity immigrant. I didn’t have a house,” remarked Banerjee, who also took it as a sign to move on from Makaibari and start Rimpocha. “Rimpocha is like the Dalai Lama, you know, it’s the reincarnated avatar. I’m a reincarnated tea avatar. There’s real, ethical, sustainable synergy with low-cost, self-funded, carbon-neutral, regenerative, holistic practices that came automatically as a gift of practising it honestly. So this can be taken and scaled up now, and Rimpocha is doing that.”