Book name- PROTO: HOW ONE ANCIENT LANGUAGE WENT GLOBAL

Author- Laura Spinney

Published by- William Collins

Price- Rs 599

Recently, standing at a tea shop in Darjeeling, I asked a shop person about the Nepali word for younger sister. The question was answered. Soon, other customers joined in, saying how their mother tongues, |all Indian languages, had similar sounding words. Those of us with a rudimentary etymological curiosity are aware of such similarities across non-Indian languages too. Linguists may not find it surprising as they

think that these languages belong to the same family. Indeed, there is a family

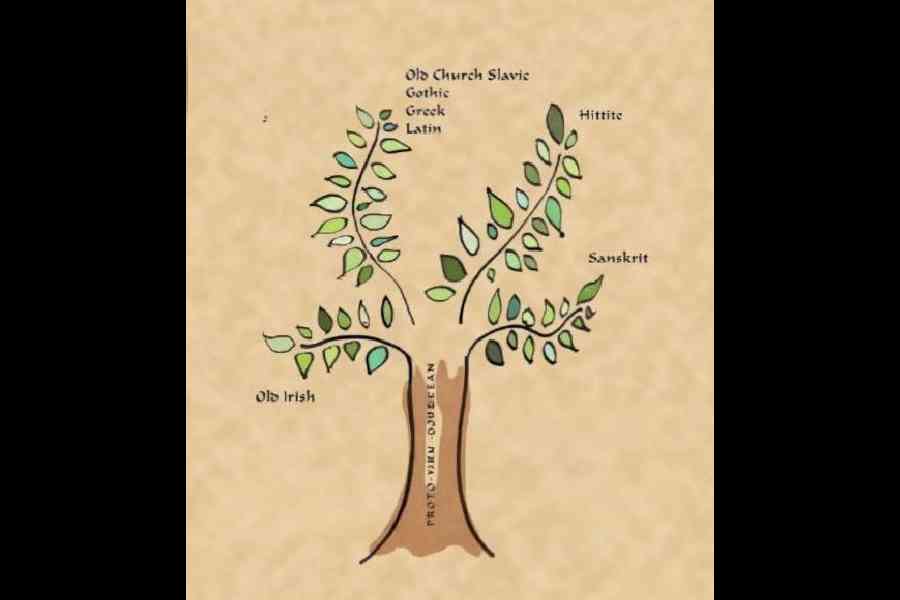

of languages called Indo-European; many of the thousands of extant languages belong to this family. Speakers of this family of languages are found in geographies ranging from Tirana in Albania to Tezpur in Assam. How, then, did this language family flourish in places that are geographically far removed from each other?

Drawing our attention to this mystery is Laura Spinney’s book that traces how the original language from which Indo-European languages have originated went ‘viral’ over many millennia, seven to be precise.

Spinney takes us on a global romp through time and space, criss-crossing

continents and civilisations, civilisations that have vanished without, in many cases, leaving signposts. Even though Spinney, while giving a detailed set of references and notes, asserts that this is not a textbook, it is quite a useful story for both laymen and experts. Using developments in three disciplines — Historical Linguistics, Archaeology and Genetics — deploying reported research as recent as 2024 and even research in progress, Spinney takes us on a journey from Lingua Obscura, the proto language from which Indo-European languages emerged, to the current trajectory of this language family. Some of the languages in the family, like Tocharian, spoken on the ancient Silk Route, have become extinct; some others, like the daughters of Sanskrit, are still around.

Interestingly, Proto, in this endeavour, also becomes a book on history, civilisations, climatology and many other ways to look at human existence.

As a poet in Maithili, I, rightly or, hopefully, wrongly, fear that this language is going to be extinct like many other Indian languages due to disuse in matters of governance, education and commerce. After reading Proto, I had moments of rather dismal, but sober, realisations. The book gives a dispassionate account of the birth and the death of languages over time that we are not accustomed to thinking about given our preoccupation with the immediate present. It also gave me personal insights as to how my Maithili, which is a Maithili that was spoken in Mithila roughly 50 years back, is now considered difficult by the current denizens of Mithila.

The style of the book is engaging, interspersing dry academic debates with real people and places in our time. In a way, it links such academic debates to the questions of here and now: for example, how the current surge of a particular kind of nationalism in different parts of the world is trying to read scientific findings to its advantage; how theories that are not so malleable to meet the demands of the political establishments may not gradually find favour.

The book also becomes a repository of hypertexts that can allow the readers to

dig deep into human evolution, the evolution of societies and cultures, over a long

period of time, thereby creating a sense of kinship across time and space as also disabusing us of the imbued sense of self importance in this long continuum.