Book name- INDIA: 5,000 YEARS OF HISTORY ON THE SUBCONTINENT

Author- Audrey Truschke

Published by- Princeton

Price- ₹1,299

Audrey Truschke’s book is yet another addition to the growing corpus of textbooks on the subcontinent’s history. In 2023, we had A New History of India, edited by Rudrangshu Mukherjee, Shobita Punja and Toby Sinclair, whose newness derived largely from its exploration of visual material as well as from its emphasis on India’s global dimensions and attention to the more peripheral regions like the Northeast that have tended to suffer historiographical neglect. In this case, too, we have the pleasure of encountering new elements integrated into a thoughtful and elegant narrative that makes a strong case for knowing India and its exceptional diversity evolving over time and for doing so with the help of discrete stories that are rich and replete with meaning and of recovering voices, especially of subordinate groups and women, from poetry, myth and artefact, to layer the narrative. With excellent bibliographic suggestions and extracts from primary — albeit selective — sources, the book is a must read for one and all. At a time when selective representations have been weaponised for stoking hatred and divisiveness and for papering over the extraordinary complexity that characterises the Indian historical experience, it is vital that readers confront genuine historical imagination, empathy, and analysis which this book is a perfect embodiment of.

For the sake of convenience, the review will identify some insights from specific chapters dealing with large thematics such as antiquity, medieval and modern transitions. In the chapters that look at India’s ancient past, Truschke examines a range of archaeological, textual and linguistic sources to weave a narrative that highlights the salience of constant migrations, the power of caste and segregation, and the power of language — of Sanskrit as a language of political communication replacing Prakrit by the second century AD. What stands out in these sections is the attention paid to the voices of the marginalised; in the chapter on Buddhism, for instance, the author chooses to look at the Therigatha to reflect on women’s status in the Buddhist order. The implicit interrogation of caste-based exclusion runs through the narrative but is always plotted in context, thereby avoiding a presentist bias. However, southern India, barring the references to early devotion and to the Cholas and to greedy Brahmins pulling a scam in temples and embezzling funds, remains somewhat under-represented.

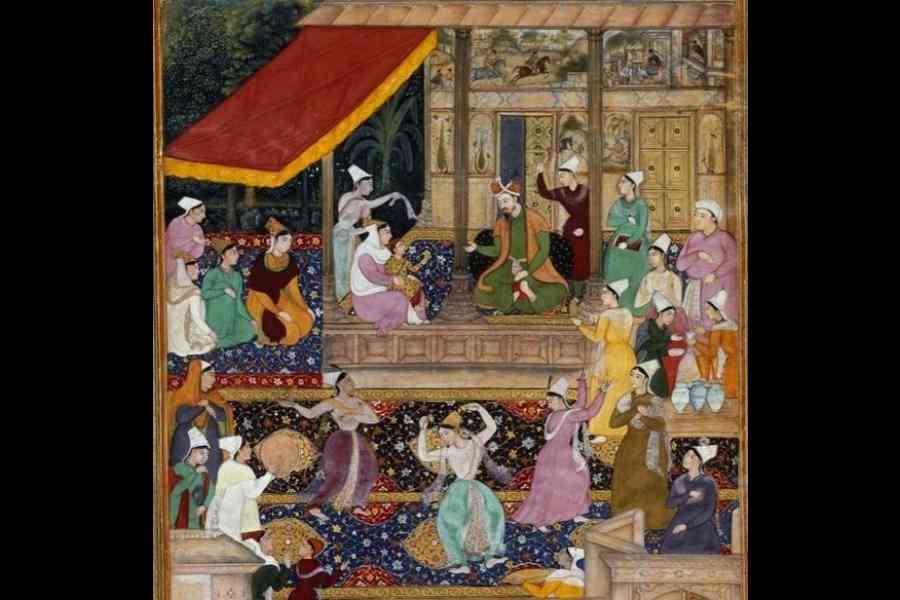

The emergence and the articulation of an Indo-Persian culture are addressed by chapters ten to sixteen. Here the author’s expertise in the field of Mughal cultural history is evident as she skilfully synthesises existing scholarship on political and commercial transformation in India under Muslim rule and introduces new elements in our understanding of the cultural ecology of Indo-Islamic rule. The irresistible appeal of Delhi under the Delhi Sultans and Mughals for merchants, migrants, mystics and mercenaries is captured evocatively just as the hegemonic influence of Persian as the language of power is highlighted, mirroring the story of Sanskrit in the previous sections. What stands out in the treatment of Indo-Islamic rule is the use of prosopography, the life stories of men like Gawan and Amber, through which Truschke attests the rich story of migration, mobility and transformation. Equally important is the author’s engagement with caste and its steady evolution over time, captured especially effectively in the chapter on the rise of Maratha and Nayaka war lineages in the 17th and the early 18th centuries. This documents not only the assertion of backward castes and their claims for Kshatriya identity as in the case of the Marathas, or a grandiose celebration of their status as in the case of the Nayakas, but also looks imaginatively at the representation of caste tensions in plays and poetry. The use of such material to invoke and interpret the past makes this exercise really appealing.

The remaining chapters deal with the processes of colonial subjugation, Indian responses and the transition to self-rule. The book ends with a nuanced appraisal of Hindutva, plotting it within the larger context of the rise of the Right globally. The sections dealing with colonial domination and indigenous response are patchy; for example, there is very little engagement with the rich scholarship on the Indian Mutiny. Admittedly, space constraints make it impossible to render an exhaustive treatment of the centuries of colonial rule and Indian transformation but the narrative that follows

empties out the complexity of the twin processes of subordination and resistance. Where it comes good is the treatment of caste as it was formalised by the official census exercise and subsequently politicised to emerge as a crucial site of debate and deliberations over social justice. In fact, the ubiquity of caste in its myriad manifestations over time is the enduring leitmotif of the work, making it an invaluable offering for those interested in making sense of Indian society with its unique fault lines.