Book: WAITING IN THE WINGS/ ENTER STAGE LEFT

Authors: Salima Hashmi with Maryam Hasan

Published by: Viking

Price: Rs 699

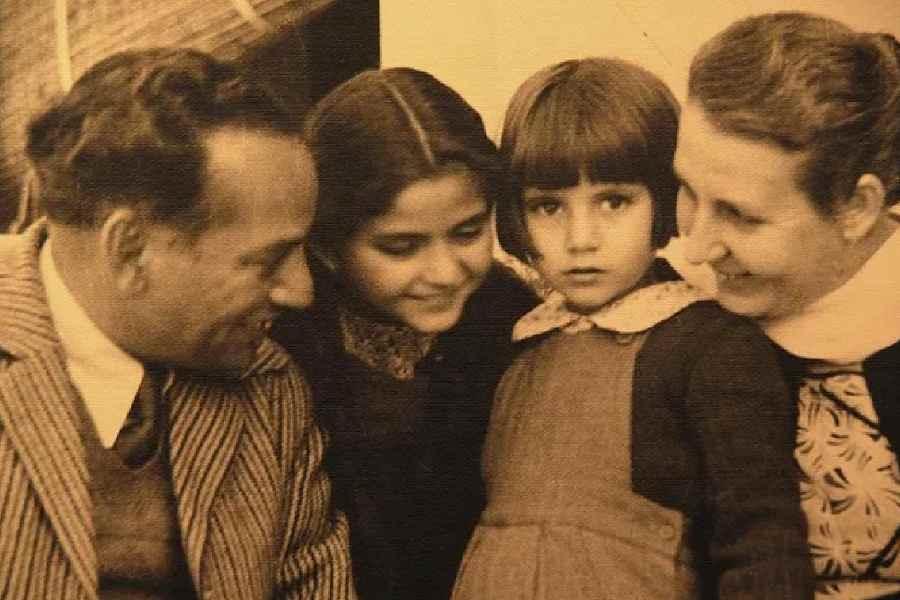

Salima Hashmi, an internationally-renowned artist, curator, contemporary art historian, and activist, is the daughter of the illustrious Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, and the writer and poet, Alys Faiz. In her two-volume work, Hashmi traverses the no-man’s-land between the autobiography and the memoir. This is so because in structure, scope, and focus, the autobiography differs from the memoir in being selective, more fluid, and deeply personal and emotional. Hashmi resorts to an emotional retelling of her intellectual, artistic life. The memoir charts the trajectory of Hashmi’s rise as an influential artist, activist, and educator while also documenting Pakistan’s cultural and political evolution through an artist’s lens.

The first volume, Waiting in the Wings, recollects the first two-and-a-half decades of her life — witnessing Partition in 1947, her father’s imprisonment in 1951, and the family’s trials and resilience as citizens of a nascent Pakistan. This part sheds light on her character formation and the development of her artistic sensibilities and perspectives on life in an atmosphere steeped in intellectual vigour and democratic values.

Hashmi details the experience of growing up in an intellectually vigorous home — its struggles and its joys — with candour. Even as the family struggles to cope, life is not without its high points. There are picnics and outings with her cousins, Salma, Mariam, and Billoo. The family home is frequented by writers, artists, and political figures, and Hashmi is privy to their conversations and arguments.

Hashmi also talks about her formative influences, such as her exposure to art, literature, and political debate within the Faiz household. Her voice recounts an intercultural environment, the interplay of love and ideology, that brought her parents together. Such insights open doors for the reader to examine the role that Alys played in Hashmi’s vision. The former’s courage as a politically active Englishwoman committed to India’s and later Pakistan’s independence and her feminist and rebellious spirit shape the young Hashmi’s perspective. The belief that art could be a tool to protest, that compassion only grew under tyranny, and the significance of each ordinary voice are recorded in these books in a calm tenor.

The second volume, Enter Stage Left, records that part of Hashmi’s life that marks the return of her and her husband, Shoaib, from the United Kingdom to Pakistan to dive into Lahore’s vibrant artistic landscape. It outlines her reinvention and contribution to the cultural renaissance in the 1970s and brings us up to date with events in Hashmis’ and Pakistan’s life until the present day.

This period was the most creatively satisfying for the couple as they innovated and experimented with the artistic form. In 1972, Shoaib and Salima conceived of, scripted, and acted in the pathbreaking and award-winning television show, Akkar Bakkar. Such Gup and Taal Matol were also hugely popular programmes in a newly-open media era. This is also the time that she took up pioneering teaching at the National College of Arts where her lectures became torchbearers of her philosophy of asking questions

and seeking answers. Especially intriguing are the events that showed how art became both refuge and rebellion for her.

A remarkable flourish achieved in the book is naming the chapters evocatively with quotes from Shakespeare’s plays: “Action is Eloquence”; “Joy’s Soul Lies in the Doing”; “What’s Past is Prologue”. The book is a skilful stitching together of events and reflections — from attuning deeply to the environment to receding to the artistic inner world. It is an act of living through memory, art, and resistance, a cultural, if not only personal, evolution of a woman balancing identity, legacy, and activism in a turbulent nation’s history.

Hashmi recounts with sensitivity and quiet restraint the period of the ascent of General Zia-ul-Haq to power in 1977. Amidst a programme of Islamisation and a clampdown on dissent, Hashmi had to deal with her father’s second spell of self-exile to Beirut between 1979 and

1982. Turning more reflective and defiant, she contextualises her personal hardship within the broader narrative of suppression and endurance.

The tone is unfiltered yet deeply empathetic in its attempt to arrest time as a caretaker of a towering legacy. As an artist, her sensitivity shines through in her treatment of the tribulations and the privileges of the educated and the emancipated. It may also be read as a homage to her parents’ vision of art being a living struggle for truth and beauty. The memoir is for those interested in subcontinental literary and artistic heritage and also in its politics.