Book name- CASTE: A GLOBAL HISTORY

Author- Suraj Milind Yengde

Published by- Allen Lane

Price- Rs 899

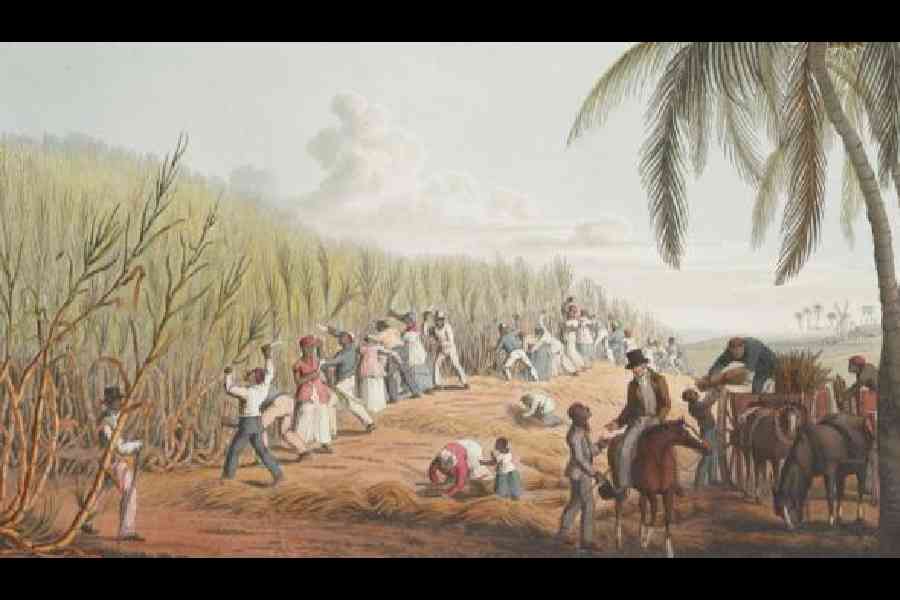

This book can be read as a sequel to the author’s previously published Caste Matters. Its principal concern is caste-based discriminatory practices and their global footprints. Unlike conventional sociological work that treats caste as a uniquely Indian institution, Suraj Milind Yengde considers caste to be a global phenomenon impacting life chances of people throughout the world: from Britain to Bahrain, Canada to South Africa. In particular, he foregrounds the Dalit experience of caste internationally, from indentured labourers in the nineteenth-century Caribbean islands to present-day migrant workers in the Middle East.

Caste: A Global History is self-consciously political and is invested in forging a cosmopolitan Dalit universalism to fight for social justice and equality. The Introduction presents an autobiographical account of the making of a Dalit scholar and academic who was brought up on the radical Dalit politics in the Marathwada town of Nanded before becoming a celebrated analyst of caste. Evidently, Yengde does not have much use for the accumulated literature on caste as it has rarely been approached and studied from the perspective of those deeply affected by social inequality and economic disadvantage imposed by the system. In other words, he decries much of the scholarship on caste as it is shorn of the lived experience. In his understanding, those scholars who are not personally affected by caste are bound to produce only external interpretations and perceptions of caste. He questions the supposed objectivity and dispassionate tone of such scholarship. As against such scholarship, his is declaredly an insider’s account of the caste system. It privileges analyses of and observations on the Indian caste system by those who have been its victims. It is their historical victimhood that enables (rather entitles) them to document the workings of the caste hierarchy not only within India but also worldwide.

The book also catalogues various anti-caste struggles in the global arena. It highlights the solidarities and the connections between anti-caste and anti-race struggles along with the limits of Dalit-Black solidarity in the United States of America. In general, the author poses searching questions regarding the impacts of colonialism, nationalism and religion on caste-based hierarchies. His discussion of the emergence of the Dalit diaspora is particularly engaging. He brings out the differences between homeland and diaspora so far as anti-caste struggles are concerned.

A highly readable work, it is bound to generate further debate on the politics of caste in contemporary times. Readers used to turgid academic prose may find the book openly polemical. In any case, Yengde has produced a highly ambitious book that will be of interest to students of society and politics in India. Those wishing to know more about the chequered trajectory of Dalit politics in India and the Indian diaspora can equally profit from the book. This book is undoubtedly infused with a much bolder vision of an equitable world and an egalitarian social order as Yengde’s arguments move across wide swathes of geographies and seamlessly bring together diaspora and homeland under their analytical gaze.